Untold Stories (60 page)

Authors: Alan Bennett

I suppose Lindsay must have seen it (Arthur Lowe was one of his favourite actors) but it would have been with a good deal of heavy sighing, looks of despair to his neighbours and even groans, a visit to the theatre with Lindsay generally something of a pantomime.

In the light of Lindsay's unrequited affections, I wanted to know if he liked the look of himself. Lambert doesn't say, though it's probably in Lindsay's diary, from which he only sparingly quotes. I would guess that he didn't, and so not expecting anyone else to either. The great loves of his

life map out his career: Richard Harris (

This Sporting Life

), Albert Finney (

Billy Liar

), Malcolm McDowell (

If

â¦) and Frank Grimes. None of them seems to have come across (if that, indeed, was what he wanted). They were all incorrigibly male and not all were over-blessed with imagination.

Reading this, to me, overwhelmingly sad memoir, I was grateful for Gavin Lambert's parallel (and much happier) experiences which thread through it. Without them the frustrations of Lindsay's life would have been unbearable to read. He was like Rattigan's schoolmaster Crocker-Harris, armoured against feeling and taken to be so by many of his associates but underneath emotionally raw and a lifetime romantic, âCan this be love?' a recurring question. He never seems to have become inured to passion or grown a thicker skin, his last love for Grimes as strong and compulsive (and futile) as his first for Serge Reggiani. Love, as he said himself, was not feasible. Sex might have made it easier, but there's some doubt if there was much of that. The theatre ought to have made it easier, too. It's a good production in my experience when people start to fall for one another, director included, but Lindsay tended to fall in love first then do the film or play afterwards, which is rather different.

The fact that all the men Lindsay fell for were straight should have been less of a problem in the supposedly permissive 1960s and 1970s, but it would have been a remarkable young man who could have got past the sarcasm and the banter and the picking you up on every word, actually to dare to lay a hand on him. A remarkable young man or, of course, a rented one, which was still a possibility in the 1970s and, pre-Aids and pre-Murdoch, quite safe, prostitution then a profession with some standards and not, as it became in the 1980s, a subsidiary of tabloid journalism. But with Lindsay such an inveterate romantic it was no more feasible than love, though one could write the scene â his pretended indifference and verbal sparring met with the boy's professional incomprehension, the shy man's reserve gradually breaking down as the master becomes the pupil.

That was one way his life might have been better, or at any rate different; the loss of his private income would have been another, if only

because the security it offered allowed him to be too choosy. There are theatre and TV directors who do productions on the cab-rank principle, taking whatever turns up next and without making too much of a fuss about it. Lindsay emphatically wasn't such a director, though some of his choices, William Douglas Home's

The Kingfisher

, for instance, might suggest otherwise. Playwrights, for their part, like to think of their plays as events and, if not looming as large in the lives and careers of their directors as their own, nevertheless constituting more than just a job of work or a way of bringing home the bacon.

The plays and films that Lindsay directed were never just jobs; often, as with the productions of

Hamlet

that he did with Frank Grimes, they were outcrops of his inner life. Even

The Old Crowd

he made part of his own story by casting old friends like Rachel Roberts and Jill Bennett, and by expanding the script to give more scope to Frank Grimes â none of which was to its detriment.

Still, it's hard not to feel that had he been directing in the 1940s, say, or under the studio system in Hollywood, he would have had to make two or three films a year, perhaps one of which might have been good. Instead, so much of his life was spent waiting around for films to be set up, working on futile development deals, with years wasted in the process. Had he been making films in the 1940s, too, they might have been war movies, which he revelled in.

Das Boot

, the submarine epic, he liked very much (âno shit about it'), and it was one of the videos that lined the shelves in his flat which he was always ready to take down and play, often with a running commentary â MacArthur's departure in

They Were Expendable

I got once after asking what âepic' meant.

He wasn't magnanimous. He was often unwilling to recognise the talents of others, particularly if they were recognised already, and especially if they were English. But he was always wonderfully, uncompromisingly himself. Gavin Lambert ends this sad, loving book with some afterwords, one of which is from Karel Reisz:

One day a man came up to Lindsay and myself in the street and congratulated us on

This Sporting Life

. He praised it effusively and called it the most

important British film in years etc., etc. We thanked him, and then he said, âBut there's a scene near the end that I don't think â¦' and got no further. âFuck off!' Lindsay said, and walked on.

In 1993 I was made a Trustee of the National Gallery at a time when free entry to

the

nation's

museums and galleries was still a contentious issue, as I hope it no longer

is today. While I was a Trustee I gave two lectures:

Going to the Pictures, which is

about my experience of pictures and galleries in general, and

Spoiled for Choice,

a

lecture to accompany Sainsbury's Paintings in Schools scheme, when I had to choose

four paintings from any gallery in Great Britain. The lectures suffer from want of all

the illustrations they had in the lecture theatre but I hope they are of some interest

nevertheless

.

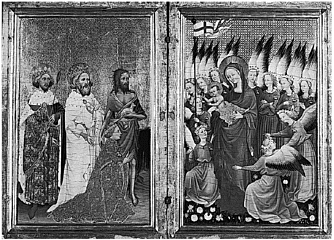

The Wilton Diptych

The first time I set foot in the National Gallery must have been early in 1957, and I came in to look at this picture, the Wilton Diptych â the two panels painted by an unknown artist in the late fourteenth century for Richard II, who kneels in the left-hand panel, accompanied by a trio of

saints: Edmund, King and Martyr; Edward the Confessor and John the Baptist, who together sponsor him into the presence of the Virgin, whose angels in a show of celestial solidarity encouragingly sport Richard II's badge of the white hart.

It was probably a portable altarpiece and in 1957 it was the only painting in the gallery that I knew anything about. This wasn't because I had any knowledge or interest in art history, which in 1957 was still something of an academic backwater, frequented so far as undergraduate Oxford was concerned chiefly by Firbankian inadequates and boys from Stowe. I knew about the Wilton Diptych because I was in my last year reading history with Richard II my special subject, and when later that year I took my degree I stayed on to do research, again into Richard II.

The research came to nothing, though humiliating memories of it return on occasions like this when I'm required to lecture. Lecturing is not a natural activity for a playwright, accustomed as one is to diffuse responsibility for one's words among one's characters, so that the audience is never quite sure you mean what you say, or you mean what they say. I only ever gave one lecture on Richard II and it was to an historical society in Oxford, the audience a mixture of dons and undergraduates. At the conclusion of this less than exciting paper I asked if there were any questions. There was an endless silence until finally one timid undergraduate at the back put up his hand.

âCould you tell me where you bought your shoes?'

It was shortly after this I abandoned history and went on the stage.

Dissolve to Boston a few years later where I was on tour with

Beyond

the Fringe

and went one free afternoon to Fenway Court, the museum and former home of the Boston heiress Isabella Stewart Gardner, famously seen in Sargent's portrait. The house had been kept much as it was in Mrs Gardner's lifetime and I remember it as being rather dowdy. It may have altered since â I was last there in 1975 â but I hope not, as it's the kind of museum one felt should be in a museum, as being very much of its time.

Much of Mrs Gardner's art collection had been put together and bought for Mrs Gardner by the expatriate American â expatriate Boston

ian in fact â the art historian and connoisseur Bernard Berenson. Mrs Gardner had died in 1924 but in 1962, when I went round the museum, Berenson himself was not long dead and biographies, diaries and commonplace books were being regularly brought out. So I got rather interested in Berenson, which, in retrospect, I wish I hadn't, as some of my anxieties about art, which is what a lot of this lecture is about, date back to that time.

Though Berenson later put together a large library of photographs, his study and listing of Italian paintings began before photographic reproductions were widely available. This to some extent dictated his method, though I suspect that with or without photographs Berenson's method would have been the same. This was, quite simply, to look and look and look, and he would stand in front of a painting by the hour together until every detail of it was committed to memory.

At some point in the course of this confrontation Berenson would experience a sense of rapture very like, I imagine, what far more people experience when listening to music. And in this connection it's no accident that Berenson's mentor when he came as a young man from Harvard to Oxford was Walter Pater, whose most famous dictum, I suppose, is that âAll art aspires towards the condition of music.'

I have to confess that I've never had a sensation of rapture, or any physical sensation in fact, standing in front of a painting except maybe aching legs or, to quote Nathaniel Hawthorne, âThat icy demon of weariness who haunts great picture galleries.' But it does happen; paintings do affect people. Take George Eliot in 1858:

I sat on a sofa in the Dresden Picture Gallery opposite the picture (it was Raphael's

Sistine

Madonna

) and a sort of awe, as if I was suddenly in the presence of some glorious being, made my heart swell too much for me to remain comfortably and we hurried out of the room.

Well, it hasn't happened to me, and having read about Berenson I took that to mean that I was lacking something, even if it was only the patience or the stamina to stand long enough looking. And though I later found that in my unfeelingness I was in distinguished company â Bertrand

Russell, for instance, Berenson's brother-in-law, complaining that pictures never made his stomach turn over either â nevertheless I felt I was failing some sort of sensitivity test and I invariably came out of galleries dissatisfied with myself.

It was not unlike the feeling I used to have coming out of church. As a boy I'd been very religious and my failure to respond to paintings on an emotional level was like my failure to respond to God: one was supposed to love Him but I didn't know what that meant. Thankfully all that was long since over, but here I was back in the same boat, only now it was Art.

Reading about Berenson engendered social anxieties too. Increasingly as he grew older the sage held court at his Florentine villa of I Tatti, where he was visited not merely by friends from the world of art but by anybody who was anybody who was passing through. No Nobel Prizewinner was ever turned away.

All his visitors were constrained seemingly without protest to fall in with his careful self-presentation and inflexible routine; few of them ever demurred, seeming to take this privileged mode of life as some sort of saintly dedication to art, with which, as I see now, it had very little to do.

That I must have been troubled about Berenson and about art, I realise in retrospect because at the time I wrote something about him. When I first started writing, in the early sixties, most of my stuff came out of being in two minds, the play or the sketch or whatever an attempt to achieve a kind of resolution. So when in 1964 I wrote a parody of an account of a visit to Berenson called

Ta Ta I Tatti

it came out of being dubious about this social sanctification of art.

In retrospect I don't know why I bothered. Re-reading about Berenson for this lecture I found him both intolerable and silly. How can you take seriously someone who had a correspondence with Ernest Hemingway about sex and wrote of himself that âHe had loved much but copulated little, although with the appreciation one would bring to a fine champagne.'

Besides being pretentious Berenson could also be a bit of a rogue. For much of his life he was on a retainer from the art dealer Duveen, which meant that some of his attributions were more self-serving than scholar

ly. He bulks more largely in the history of American museums and galleries than he does here, though he figures in a complicated saga to do with the acquisition of Titian's

La

Schiavona

, which came to the National Gallery in 1942 and which Berenson originally thought was a copy of a lost Giorgione.

He was also indirectly involved in the purchase of the group of paintings by Sassetta now in the Sainsbury Wing, which Kenneth Clark bought when he was Director, probably for an inflated sum and again through Duveen, who was also a trustee. Trust, it has to be said, was not Duveen's strong suit.

If as a young man I'd had to put into words what my response was to pictures I'd have said I liked paintings that had what I thought of as a

glow

to them. That is what drew me across a room to a picture and (I say this slightly shamefacedly) made me want to take the picture home. It never came to that, but around this time I did buy one or two early nineteenth-century glass paintings which, whatever their artistic merits, do have, as does all painting on glass, a translucent glow.

It's only too easy to demonstrate what I thought of â still think of, I suppose â as this glow. Chosen almost at random there is Bellini's

Agony

in the Garden

, the glow there coming, I suppose, from the approach of dawn, just as in Giorgione's

Il

Tramonto

it's the light of sunset; whereas in this

Portrait of a Young Man

by Catena it could be thought to be the glow of youth.

Then there's the rather cosy glow of Antonello's

St Jerome in his Study

. Because its flesh was not supposed to decay the peacock was a symbol of immortality and resurrection. Less well known is the fact that it was supposed to scream at the sight of its own feet, not recognising them as its own â a predicament with which one sympathises more and more as one gets older.

Technically, particularly with Venetian pictures, the glow is often to do with glazes and the accumulation of glazes which give depth to the painting. Sometimes, too, it has to do with the colour tones being close together but, whatever it is, all I can say is that I know it when I see it,

which is of course intellectually not very respectable or communicable. So it was fortunate that around this time, the late sixties, I began to be aware that pictures had another aspect and so began to take an interest in art history.

Of course I wasn't alone in this, as it was in the late sixties that the boom in art history really began to take off. The history of the history of art in England in the second half of the twentieth century would make a fascinating study as it would have to take in, be a sidelong look at, all sorts of other developments â the beginning of the colour supplements, for instance, and the expansion of newspapers and illustration, the ungentri-fication of Sotheby's and Christie's, the notion of the heritage and even, though one winces to say so, the

Antiques Roadshow

.

Crucial to the development of art history in this country was the arrival here in the thirties of refugee art historians from Nazi Germany, many of them iconographers. Now Berenson had had little time for iconography, being more taken up with what a painting looked like than with what it might mean. This seems pretty obviously short-sighted as one of the bonuses of iconography, of unpacking the meanings within a picture, is that you are detained longer in front of it; like sleeping policemen, iconography slows you down and you have to dwell on the picture with a particular purpose in mind and then, as a side effect (and side effect is exactly the right word because it's something that happens out of the corner of the eye), the beauty of the painting, which is hard to confront directly, begins to be unwittingly taken in. As E. M. Forster says, âOnly what is seen sideways sinks deep.'

*

To find, though, that paintings could be decoded, that they were intellectual as well as aesthetic experiences, was something of a relief because it straight away put them in a familiar and much more English context if only because a lot of iconography, saying who's who and what's what in a painting, could be taken as a higher form of that very English preoccupation, gossip.

Emmanuel de Witte,

Adriana van Heusden and Her Daughter

at the New Fishmarket

in Amsterdam

Take the portrait of

Adriana van Heusden and Her Daughter at the New

Fishmarket

in Amsterdam

by the seventeenth-century Dutch painter Emmanuel de Witte. Now it helps to know the gossip about this picture which is that when he painted it de Witte was on his beam ends, and that by an undertaking he'd entered into with his landlord everything he painted was to belong to him in return for board and lodging. And that Adriana van Heusden, who looks pretty formidable even over the squid and skate, was his landlord's wife.