Untold Stories (63 page)

Authors: Alan Bennett

It's a sentiment I later put into the mouth of Hector, the eccentric schoolmaster in

The History Boys

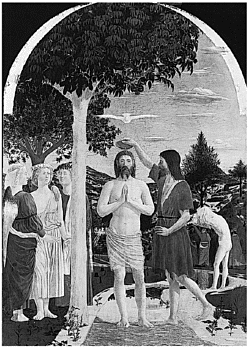

, but something similar, which one might call evidences of humanity, happens in pictures. The most notable example in one of the most popular paintings in the Gallery is in the Piero

Baptism

⦠and it's the man taking off his shirt. There's something obscurely comforting in the fact that they took their shirts off 500 years ago much as we do now, this piece of naturalism more vivid for its contrast with the hieratic figures of Christ and the Baptist in the foreground who are, of course, like all the figures in Piero's pictures, stern and unsmiling. They wouldn't get far advertising toothpaste, Piero's people.

Piero della Francesca,

The Baptism of Christ

In Piero's

Nativity

, another favourite picture, there's an oddly modern piece of observation where Joseph is relaxing in the background, one leg

resting on the other and showing the sole of his foot. In view of this relaxed behaviour one might be forgiven for thinking that Joseph is celebrating the birth of the baby by smoking a large cigar. But that's an illusion, and not the kind of illusion Sir Ernst Gombrich specialises in.

Paradoxically, animals are often there in paintings to introduce the human touch. In Catena's

A Warrior Adoring the Infant Christ

it's a little dog. In Hogarth's

The Graham Children

the cat has maybe jumped up to get at the bird, but it's also for the sheer pleasure of clawing the upholstery. In Veronese's

The Family of Darius

a monkey is distracting one of the little girls, or maybe alarming her, as it's quite a sizeable creature.

Cats and monkeys enable me to say that the

News of the World

used to have on its masthead, if it could be called a masthead, the motto âAll human life is there'. I shouldn't think anybody on the paper knew the source of the quotation, which in full reads âCats and monkeys, monkeys and cats, all human life is there.' And the author â about the most unlikely person one would think of in connection with the

News of the World

â is Henry James.

Piero della Francesca,

The Nativity

Staying with Veronese, the most affecting touch in the painting isn't the children, though, or the monkey, it's Alexander himself. He's portrayed as a very young man, and here is someone who is the master of the known world but who still can't quite manage to grow a satisfactory beard. I find that very human.

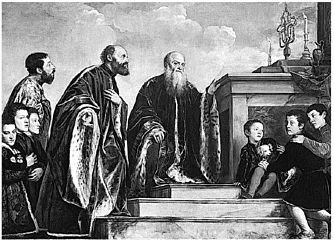

In Titian's

The Vendramin Family

the children are generally what strikes one as most human, especially the little boy with the dog, but the most appealing figure is Leonardo Vendramin, who seems much less impressive than his father or his uncle, a bit weak, simple almost, and the only one in the picture whose entire attention is fixed on the relic on the altar, which is what the picture is ostensibly about. He's like one of the weaker brothers in

The Godfather

who you know will end up getting bumped off.

Titian,

The Vendramin Family

Finally in this catalogue of human touches,

The Mantelpiece

by Vuillard, whom I think of rather perversely as a French Harold Gilman â simply because Leeds Art Gallery, where I first discovered paintings, has a very good collection of Camden Town paintings which I got to know long before I ever saw any French paintings of the same date. This could be in Camden Town. I love the mantelpiece; I love the wallpaper; I wish it were my mantelpiece and my picture.

I was going to end on a rather clichéd note by saying that we shouldn't take the National Gallery for granted. But of course the opposite is true;

the more institutions and freedoms and benefits one can take for granted â of which in my view free state-supported galleries and museums come high on the list â the more civilised a society is. Free public libraries are another, but we certainly can't take them for granted. Around the time I was beginning to write this lecture I read a piece by Madsen Pirie, the Director of the Adam Smith Institute, dismissing public libraries as simply providing free entertainment for the middle classes. When such views can be so unabashedly expressed and taken seriously by government a free National Gallery can't be taken for granted at all.

Not having to pay to come into the Gallery doesn't mean that one does-n't value it. One of the most rampant misapprehensions of the last fifteen years has been the notion that we only value what we pay for, and that to be given something â even when what is supposedly being given is actually our own, as these pictures are â means that we set no store by it. All my experience, and in particular my education, for which my parents never had to pay a penny, belies that.

In my view we should put no obstacle, financial or otherwise, between the people and their pictures. They belong as much to a boy or girl sleeping in a doorway in the Strand as they do to the benefactors whose names are emblazoned on these walls. With its lectures and educational programmes what has been created here in the National Gallery, particularly over the last ten years and in the teeth of the prevailing orthodoxy, is a free university of art, free and to a high standard. It does a wonderful job.

But like most public institutions today the Gallery is required not merely to do its job but also to prove that it is doing its job. It is an exercise that is at the same time self-defeating and self-fulfilling. The current orthodoxy assumes that public servants will only do their job as well as they can if they are required to prove that they are doing their job as well as they can. But this proving takes time, and the time spent preparing annual reports and corporate plans showing one is doing the job is taken out of the time one would otherwise spend doing it⦠thus ensuring that the institution is indeed less efficient than would otherwise be the case. Which is the point the Treasury is trying to prove in the first place. And

every public institution now is involved in this futile time-wasting merry-go-round.

Necessary to this merry-go-round is another misapprehension, namely that everything is quantifiable, that what visitors to the Gallery come away with can be assessed by means of questionnaires and so on. Well, maybe 20 per cent of it can, and maybe 20 per cent of all these efficiency-inducing exercises are worthwhile, or worth the hours and hours of time and form-filling they take up. And yes, one can gauge from a questionnaire how quick the service is in the café or how clean the lavatories are, but it cannot be said too often that the heart of what goes on here, the experience of someone in front of a painting, cannot be assessed and remains a mystery even, very often, to them.

Another contributory misapprehension is that people always know what they want from the Gallery. It's not condescending to say that they don't. If most of the visitors here were single-minded and coming in just to look at the pictures the Gallery would be a much emptier place.

The truth is people come in for all sorts of reasons, some of them just to take the weight off their feet or to get out of the rain, to look at the pictures perhaps, or to look at other people looking at the pictures. And the hope is, the faith is, that the paintings will somehow get to them and that they'll take away something they weren't expecting and couldn't predict.

So I'll end with a tired shopper or someone coming home from work with half an hour to spare before catching the train at Charing Cross. Not really looking at anything in particular, and maybe not far from the entrance, they come across a picture of some towels drying on a balcony in Naples in 1782. It was painted by Thomas Jones and is scarcely a picture at all, more like a fragment of a building, the kind of thing you see out of the corner of the eye. And maybe that's how the tired commuter sees it. But I've got great faith in the corner of the eye and with that remark of E. M. Forster that I quoted earlier: âOnly what is seen sideways sinks deep.'

Four paintings for schools

When I was at school in the late forties there were two sorts of paintings on the walls. Most classrooms hosted a couple of pictures scarcely above the Highland-cattle level that had been discarded by the City Art Gallery and palmed off on the Education Committee, which then sent them round to schools. These uninspired canvases didn't so much encourage an appreciation of art as a proficiency at darts. However, there was another category of picture occasionally to be seen: reproductions on board of work by modern British painters â Ravilious, Paul Nash, Henry Moore, Pasmore. These, I think, were put out by Shell and turn up occasionally nowadays at auction, though not quite at Sotheby's. That I've always liked â and found no effort in liking â British paintings of the forties and fifties I partly put down to my early exposure to these well-chosen reproductions. So it was my own largely unwitting experience that made me welcome the Sainsbury scheme whereby every year four selected paintings are reproduced, framed and sent round with an information pack to schools local to Sainsbury's stores.

To be asked to choose four paintings from any of the galleries in the British Isles feels, I imagine, not unlike taking part in that dreadful TV game in which contestants are each given a trolley and the run of a supermarket and, dashing frantically between the cling peaches and the minced morsels, end up with far more Jeyes Fluid than any sane person could reasonably want. The supermarket, I hasten to add, not Sainsbury's.

As a Trustee I felt that one of my paintings should be from the National

Gallery and I originally wanted

The Good Samaritan

by Bassano. It may seem, in view of its much more spectacular neighbours like Veronese's

The

Family of Darius before Alexander

or Titian's

Bacchus and

Ariadne

, to be a dull choice. Indeed this rather intimate picture is an exception for Bassano himself, who produced much more spectacular paintings, one of which, a tumultuous Nativity in the National Gallery of Scotland, at one point I had it in mind to choose.

The Good Samaritan

is quite low key, the Samaritan caught just as he's trying to heave the injured man onto his horse; it's an awkward movement because the man is either unconscious or unable to do much to help and the tension of the effort runs right across the picture. In the background the priest and the Levite, having chosen not to see the injured man, are making off. In the distance is the town where the Samaritan will pay for the man to be lodged until he recovers, the town thought to be a representation of the painter's home, Bassano near Venice.

So many paintings in galleries are populated by the beautiful and the perfectly proportioned that it's a relief to find one of this date (mid-sixteenth century) where the characters are so downright ordinary. These are no gods, or athletes even: just one balding, middle-aged man helping another, their bodies worn and slack and past their best. That seemed to me to be something that a child could learn from â apart, of course, from the relevance of the parable itself, and particularly the fact that Samaritans were rather looked down on in their day, which points up the contrast between the priest and the Levite, who ought, if they were sincere in their beliefs, to have lent a hand, and the despised figure who actually did help. It's as if you've broken down on the M6 and the only person who bothers to stop and help is a Hell's Angel.

Having decided this was one of the paintings I wanted, I was told that it wouldn't reproduce well, so I had to look elsewhere.

An obvious choice was the spectacular painting of St George and the Dragon by the Spanish painter Bermejo, which the National Gallery acquired a couple of years ago. Wherever you look in this painting there is something that delights: in particular, the vivacious and many-mouthed

dragon â it even has mouths in its elbows. St George looks a little baby-faced but his armour makes up for it, particularly the reflections in his breastplate, which are said to represent the Heavenly City but look not unlike All Souls College, Oxford. Having chosen this painting, I was looking forward to the umpteen papier-mâché versions of the dragon â with or without egg boxes â that the children would inevitably construct. But again my choice was thwarted. The painting is long and thin and I was told it would be difficult to reproduce without a vast border of white â and since borders are something I hate I had to look elsewhere.

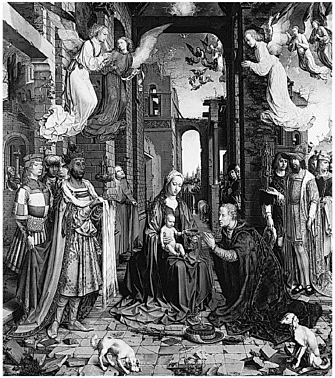

Jan Gossaert,

The Adoration of the Kings

I finally chose

The Adoration of the Kings

by Gossaert, also called Mabuse, which hangs in Room 12 of the Gallery. There's such a lot going on in it that it's hard to take it all in: the Holy Family below, confronted by rich visitors and attendants plus a crowd of onlookers, the sky above buzzing with a flotilla of angels. The picture is painted in extraordinary detail, every bit of it in focus â which is partly why it seems so crowded

and confusing. Caspar is offering the Christ child a gold chalice filled with coins, the lid of the chalice lying on the floor. Balthazar on the left is identified by an inscription on his crown, and Gossaert has painted his own name below it (and again on the neck ornament of Balthazar's black servant). On the right, Melchior is waiting with his presentation rather precariously balanced in his limp hand. The detail is such that one can distinguish the hairs on the mole on Caspar's cheek. Above the scene, and in another order of things, the angels crowd the sky, where the star that led the Wise Men to the manger is still shining. A dove representing the Holy Spirit descends from the star.

Gossaert was an artist from near Antwerp, painting in the first quarter of the sixteenth century, and this picture was done as an altarpiece for the Abbey of Grammont in Flanders around 1510. Somewhere on the painting the restorers at the National Gallery have found Gossaert's own fingerprints. It's a painting that cries out to be made into an Advent calendar, though there would be an insufficiency of windows to display all its wonderful detail. And yet I always feel that it's with the Adoration of the Kings that the Christian story begins to go wrong; that the unlooked-for display of material wealth and the shower of gifts, for all their emblematic significance, are a foretaste of the wealth and worldliness that were to ensnare the medieval Church; and while the Virgin, always the perfect hostess, takes it all in her stride, even in this painting, accepting the chalice of coins proffered by Caspar, it nevertheless bodes ill for the future.

As is generally the case with the Adoration, it's the animals who get it right, even though, as here, they scarcely figure, shouldered out of the way by the Kings and their arrogant followers, the young man on the left, for instance, the picture of boredom and superciliousness. In the Bassano

Nativity

the animals scarcely manage to get their noses in the painting at all. Here they do a bit better, as the ox keeps company with Gossaert himself, just peeping into his own painting, while the ass is at the back of the picture, where the sightseers are gazing over the ramshackle fence. The dogs, being dogs, get more of a look-in than the ox and the ass. They seem

to be quite posh dogs and probably came with the Kings, both having distinguished pedigrees, the one on the left taken from Schongauer's engraving of

The Adoration of the Kings

, the other from Dürer's

St

Eustace

.

One way of looking at this extraordinary painting is as an advertisement for the Flanders Tourist Board, or as the equivalent of one of those airport bazaars where all the products of the locality are on sale. Embroidery, millinery, jewellery, leather, fancy goods â it's all here. On this view, the Three Kings in their elaborate apparel could be seen as fugitives from the catwalk â and like anyone dressed at the very height of fashion, startling and not unridiculous.

This way of looking at the painting isn't entirely a joke, though, because if one wants a prime site from which to advertise, what better place than the altar?

The character and situation of Joseph interest me partly because in most paintings of this period, and until the end of the sixteenth century, he has to take a back seat, particularly in paintings of the Adoration. He's often so much in the background that one wonders if his role in the Holy Family, which is in any case ambiguous, isn't made more so by his persistence in keeping out of the limelight. It must have been very puzzling. One can imagine a conversation between the Wise Men:

âWho's the guy with the grey hair?'

âThat's the

husband

.'

âOh my God!'

And so it must often have been with Joseph, his situation not helped by his always being represented as getting on in years. This is possibly because he's not mentioned in the New Testament after the Presentation of Jesus in the Temple, Jesus then being twelve, and so is presumed to have died before Jesus' ministry began.

Even when Joseph is not depicted as old he is often made into such a pathetic and eccentric figure as almost to reflect discredit on the Virgin, who picked him out in the first place. But I suppose that to portray him as an old man or a bit of a fool bolsters the doctrine of the Virgin Birth. After all, there is a sense in which Joseph is cuckolded by the Holy Ghost, a

notion which is easier to accept if he fulfils the familiar role of the elderly and foolish husband of a much younger wife. Indeed, in some mystery plays he was presented as a cuckold.

It's hardly fair and one feels that he's rightly a saint, if only because, having to play second fiddle, he needs to be. It's a situation one sometimes comes across in show business, the famous actress with the supportive spouse; and while Joseph hasn't quite had to sacrifice carpentry to the demands of his wife's career, he's definitely No. 2 in this marriage, a male wife in fact.

In Gossaert's

Adoration

he shrinks into the background as usual, but it's nice occasionally to find a painting in which he doesn't and where the Wise Men pay him a proper degree of attention. There is, for instance, an

Adoration

by Giovanni di Paolo in the Linsky Collection at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, in which one of the Wise Men has his arm round Joseph's shoulder and is also holding his hand, perhaps saying: âWell, I know what it's like to be woken up in the middle of the night. I've got children of my own.' Nice, too, when Joseph so seldom gets to hold the baby, to find him in a painting from the Paris Hours of René of Anjou, helping to bathe the baby and, in a fifteenth-century Book of Hours from Besançon, sitting by the fire, airing Jesus' nappy.

Looking at the extraordinary gifts brought by the Three Kings, a child might well wonder what happened to them while Jesus was growing up. The myrrh is traditionally said to have been used to anoint Christ's body after the Crucifixion. But what of the cup? Did it foreshadow the cup from which he drank at the Last Supper? Did Mary and Joseph ever take it down from its shelf, unwrap the cloth in which it was kept and think back to that extraordinary time when kings and their retinues paid them court and pitched camp around their stable? Which, in Gossaert's painting, isn't a stable at all but a derelict palace, the run-down building a symbol of the teachings of the Old Testament, which Christ would now supersede and make new and so build his own temple.

Painters of this period never get the baby right. He's always far too big, as he is here, and frequently looks as if he knows exactly what's going on,

the problem for the painter being that, if he is the personification of God, he would know what was going on, and how do you represent that? But almost all of the babies depicted in paintings of the Nativity, sometimes spindly, sometimes gross, were they taken along to a baby clinic today would arouse concern. A paediatrician would have to ask Mary some very searching questions.

The National Gallery is particularly rich in Gossaert's work, not all of which I like, but none of his other paintings is as spectacular as the

Adoration

. One recent addition to the canon is a

Virgin and Child

, previously thought to be a seventeenth-century copy but which, when cleaned, was shown to be the genuine article. What to me is remarkable about this painting is that if you glance back at it from the door of Room 12 the illusion of it being three-dimensional is so strong that the Virgin looks as if she is a wax figure. It's as startling an effect as the anamorphic skull in Holbein's

The Ambassadors

or the perspective tricks of the Hoogstraten Box. As a painting, though, I'm not particularly keen on it because the Virgin looks as if she is enthroned in a Victorian fireplace.

Hanging next to Gossaert's

Adoration of the Kings is Portrait of a Man

aged 38

by Lucas van Leyden, painted around 1521. The age of the sitter is written on the scroll that he's holding and, given his somewhat doleful countenance, if it said forty rather than thirty-eight it would be rather funny. I find it hard to say why I like the painting so much. It's partly the austerity, which brings to mind some of Lucian Freud's early portraits, while the sitter reminds me of Max von Sydow in

The Seventh Seal

. When I go through Room 12 it's the painting I always glance at as if it were a friend. I haven't got anything more to say about it than that, though, and I couldn't choose it as one of my four pictures because it, too, must seem rather dull. But I love it and I think it's a reminder â and not one that all art historians would welcome â that about some paintings there isn't all that much to be said.