Wallach's Interpretation of Diagnostic Tests: Pathways to Arriving at a Clinical Diagnosis (1347 page)

Authors: Mary A. Williamson Mt(ascp) Phd,L. Michael Snyder Md

BOOK: Wallach's Interpretation of Diagnostic Tests: Pathways to Arriving at a Clinical Diagnosis

6.89Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen:

Last antibodies to appear and are rare in acute phase; develops 4–6 weeks after onset of clinical illness and rises during convalescence (3–12 months) and persists for many years after illness. Absence when IgM-VCA and anti-D are present implies recent infection. Appearance early in illness excludes primary EBV infection. Appearance after previous negative test evidences recent EBV infection.

Use

Diagnosing IM. In patients with suspected IM and a negative heterophile test.

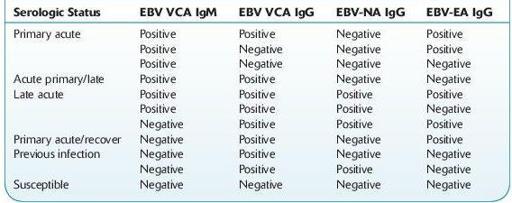

Interpretation

Table

17-1

TABLE 17–1. Interpretation of Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) Serologic Status

Limitations

EBV serology testing should not be performed as a screening procedure for the general population. The predictive value of a positive or negative result depends on the prevalence of analyte in a given patient population. Testing should only be done when clinical evidence suggests the diagnosis of EBV-associated infectious mononucleosis.

Antibodies to EBV have been demonstrated in all population groups with a worldwide distribution; approximately 90–95% of adults are eventually EBV seropositive. EBV acquired during childhood years is often subclinical; <10% of children develop clinical infection despite the high rates of exposure.

The false-negative rates are highest during the beginning of clinical symptoms (25% in the first week; 5–10% in the 2nd week, 5% in the 3rd week).

Approximately 10% of mononucleosis-like cases are not caused by EBV. Other agents that produce a similar clinical syndrome include CMV, HIV, toxoplasmosis, HHV-6, hepatitis B, and possibly HHV-7.

IgM and IgG antibodies directed against viral capsid antigen have high sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of IM (97% and 94%, respectively).

ESCHERICHIA COLI

(ENTEROHEMORRHAGIC, SHIGA TOXIN– PRODUCING

E

.

COLI

, STEC,

E

.

COLI

O157:H7) CULTURE (RULE OUT)

Definition

Other books

Deadeye Dick by Kurt Vonnegut

The Gift of Asher Lev by Chaim Potok

On Deadly Ground (Dan & Chloe Book 2) by Flamank, Nathan L.

Crossing Boundaries (Cape Falls) by Crescent, Sam

Family Drama 4 E-Book Bundle by Pam Weaver

The Bat by Jo Nesbo

The Soldier by Grace Burrowes

Betrayal by Lady Grace Cavendish

Unclean by Byers, Richard Lee