Where I Belong (19 page)

Authors: Mary Downing Hahn

We walk along the trunk from its huge root ball until we lose our way in a forest of small branches. Shea pats a place for me to sit beside her. The trunk's so big that our feet dangle above the ground.

I catch sight of three deer moving slowly through the trees, their backs dappled with sunlight. They stop and stare at Shea and me with big brown eyes, their ears erect.

“If you squint and make them blurry, they could be unicorns,” Shea says.

“But they're not,” I say.

Shea sighs. “Well, even if they are just deer, they're still beautiful and kind of magical. Don't you think so?”

I lean forward and study the deer. They stand so still, their heads up, their ears perked, their eyes focused on us as if they want to know who we are and if they can trust us. The trees encircle them and I feel the power of those trees. As silent and motionless as the deer, the trees watch us, too. If we make one wrong move, the deer will disappear into the woods without a sound. But the trees will stay where they are, held fast by their roots but vigilant.

I glance at Shea. Her eyes fixed on the three does, she's as still as the deer and the trees. Will she understand if I tell her about the trees and their magic? Or will she think I'm out of my mind?

While I hesitate, the deer walk slowly toward us, crossing the clearing step by step, never taking their eyes off us. Behind them, a breeze moves through the leaves, and I imagine I hear the Green Man's voice telling the deer we won't harm them.

The deer stop about two feet away, too far to touch them but close enough to see our reflections in their eyes. They smell like the woods, mossy and fresh. It's as if time has stopped and anything might happen. I realize I'm holding my breath and I let it out slowly. One deer lowers its head and makes a whuffing sort of sound.

In the softest voice I've ever heard, Shea whispers hello to the deer. The smallest of the three stretches its neck toward Shea and makes the whuffing sound again. If Shea raised her hand, she could touch the deer's soft nose, but she doesn't move. Neither do I.

Then, as if on signal, their white tails shoot up and they leap away. In an instant, they're gone, swallowed up by the woods.

Shea turns to me. “Do you think the Green Man sent them?”

I stare at the wall of green that hides the deer. “He might have. It's what he'd do ifâ”

We look at each other, still wanting to believe. The trees stir, the leaves whisper, a crow cries, its harsh voice filled with the dark wisdom of the forest. In my mind's eye, I see the Green Man at the edge of the woods. He raises a hand to wave, then vanishes into shadows.

In the distance, a train whistle blows. I slide off the tree trunk and Shea drops down beside me. Silently, we walk through the woods, toward home.

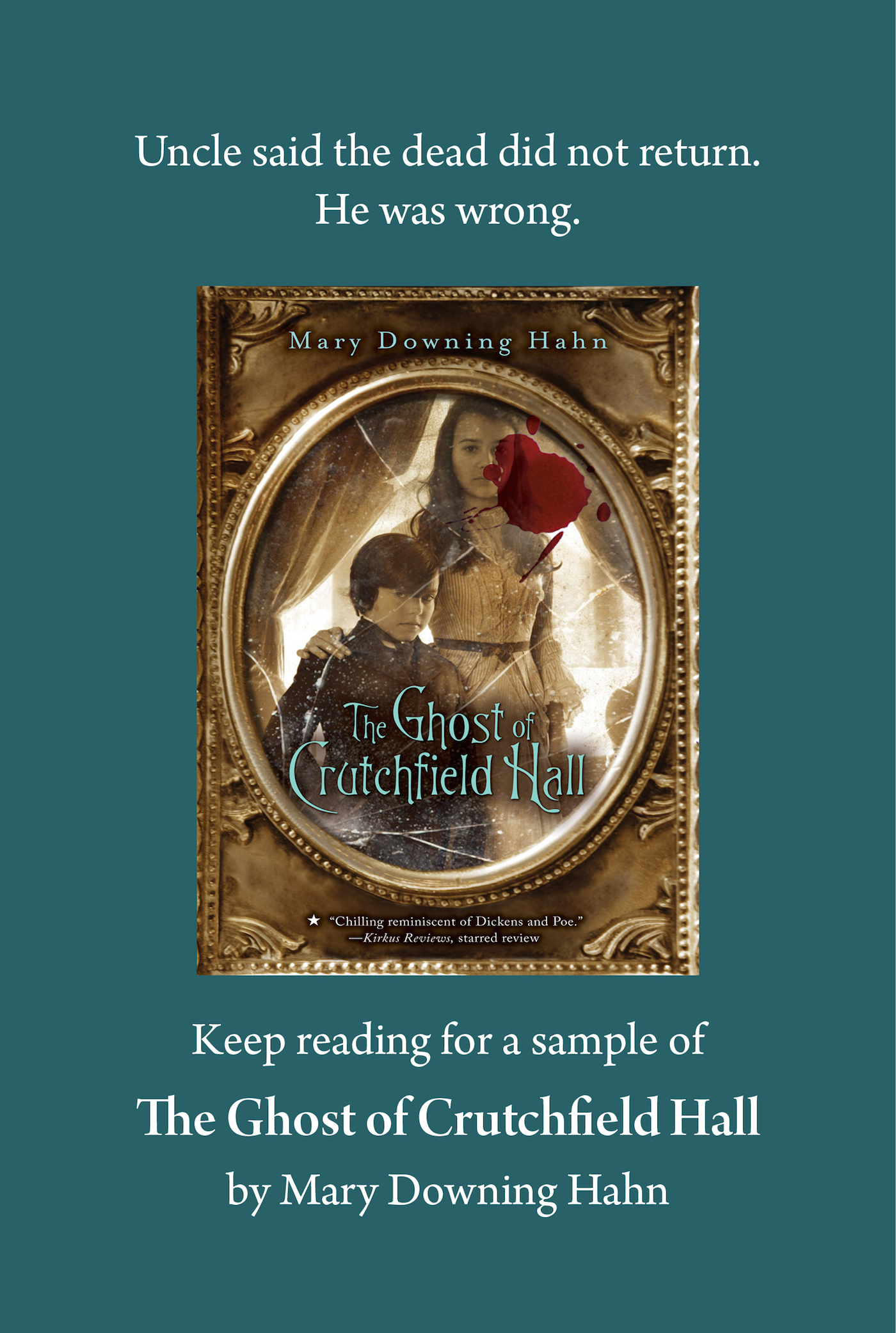

“T

AKE GOOD CARE OF THIS GIRL

,” Miss Beatty told the coachman. “She's an orphan, you know, and never set foot out of London. Make sure she gets where she's going safely.”

After turning to me, Miss Beatty smoothed my hair and checked the note she'd pinned to my coat: “Mistress Florence Crutchfield,” it read. “Bound for Crutchfield Hall, near Lower Bolton.”

“Now, you behave yourself,” she warned me. “Don't talk to strangers, no matter how nice they seem, sit still, and don't daydream. Keep your mind on what you're doing and where you're going.” She paused and dabbed her eyes with her handkerchief.

“And when you get to your uncle's house . . .” She sniffed and went on, “Be a good girl. Do as you're bid. None of your mischief, or he'll be sending you back here.”

Unable to restrain myself, I threw my arms around her. “I'll miss you.”

Miss Beatty stiffened a moment, as if unaccustomed to being embraced. Certainly I'd never had the nerve to do so before.

“Now, nowâno tears.” She gave me a quick hug, then stepped back as if she'd done something wrong. Affection of any sort was not encouraged at Miss Medleycoate's Home for Orphan Girls. “Remember your manners, Florence. Always say please and thank you, and don't slurp your soup.”

“Is that girl coming with us or not?” the coachman asked.

“Go along then, Florence.” Miss Beatty gave me a gentle push toward the coach. As a passenger held out his hand to assist me, she said softly, “I pray you'll be happy in your new home.”

Once inside the coach, I looked out the window just in time to glimpse Miss Beatty's broad back vanish into the crowd in the coach yard. The last I saw of her was the big yellow flower on her hat. She was the only grownup at Miss Medleycoate's Home for Orphan Girls who'd treated meâor any of usâwith kindness.

On his rooftop seat, the coachman cracked his whip, and away we went, bouncing over cobbled streets and rattling through parts of London I'd never seen. I glimpsed the Tower, the dome of St. Paul's Cathedral, and mazes of twisting alleyways. Then we hurtled across Tower Bridge and into the narrow streets of Southwark, crowded with coaches, wagons, and people, all doing their best to move onward at the expense of everyone else.

In the crowded coach, I was squashed between a large redheaded woman and an even larger gentleman with a beard that threatened to scratch my cheek if I was jostled too close to him.

Directly opposite me sat a narrow-faced young man with a mustache and a wispy beard, attempting to read his Bible. Next to him a rough-looking fellow frowned and scowled at all of us. Making herself as small as possible, a timid lady with gray hair and spectacles pressed herself against the side of the coach.

Before five minutes had passed, the gentleman beside me fell asleep and commenced to snore loudly. On my other side, the stout woman fussed to herself and even went so far as to reach across me and poke the sleeper with her umbrella. She failed to rouse him.

Across from me, the rough fellow began a conversation with the Bible reader, which soon turned into an argument about Mr. Darwin's theory of evolutionâthe Bible reader for and the rough fellow against. The old lady closed her eyes and either fell asleep or feigned to.

The woman beside me opined that she was not descended from apes, no matter what Mr. Darwin had thought. She did not, however, voice her opinion loudly enough to be heard by the Bible reader and the rough fellow.

While all this went on about me, I mused upon the sudden change in my circumstances. My parents had drowned in a boating accident when I was five years old. When no relative stepped forward to claim me, I was sent to Miss Medleycoate's, where I spent seven wretched years learning to sew and read and write from a series of strict teachers who had little patience with girls who could not stitch a neat row or learn their arithmetic. We were cold in the winter, hot in the summer, and hungry all year round. If we dared to complain, we were beaten and locked in the punishment closet.

Then one day, just a week ago, a solicitor appeared at the orphanage and informed Miss Medleycoate that I was the great-niece of Thomas Crutchfield, my father's uncle. My uncle had searched for me a long time and had finally learned my whereabouts. As soon as proper arrangements were made, Mr. Graybeale said, I was to live at Crutchfield Hall with my uncle, his spinster sister, Eugenie, and my cousin James, the orphaned son of my father's only brother.

Glancing around the dreary sitting room, Mr. Graybeale had told me I was a fortunate girl.

“She certainly is.” Miss Medleycoate fixed me with a sharp eye. “I am certain Florence will show her gratitude as she has been taught.”

I knew full well how fortunate I was to escape Miss Medleycoate's establishment, but I merely bowed my head to avoid her stare. Now was not the time to express my feelings.

“What sort of boy is my cousin James?” I asked Mr. Graybeale. “Is he my age? Is heâ”

“I've never met the child,” Mr. Graybeale said, “but I hear he's rather delicate.”

I stared at the solicitor, wondering what he meant. “Is he sickly?”

“Florence,” Miss Medleycoate interrupted. “Do not pester the gentleman with trivial questions. Your curiosity does not become you.”

“It's all right,” Mr. Graybeale told Miss Medleycoate. Turning to me, he said, “The boy has suffered much in his short life. His mother died soon after he was born, and his father succumbed to a fever a few years later. Not long after James and his older sister, Sophia, arrived at Crutchfield Hall, the girl was killed in a tragic accident. So much loss has been difficult for James to bear.”

I stared at Mr. Graybeale. “I'm so sorry,” I whispered. Perhaps I should not have asked about James's health, but if I had not, how would I have known about my cousin's tragic past and Sophia's death? Disturbing as these events were, I needed to be aware of them, if only to avoid asking my aunt and uncle inappropriate questions.

With a rustle of silk, Miss Medleycoate rose to her feet. “I believe Mr. Graybeale has satisfied your unseemly curiosity, Florence. You may return to your lessons while I sign the necessary papers.”

Now, as the coach bounced and swayed over rough roads, I thought about Sophia. If only she hadn't died, if only she were waiting for me at Crutchfield Hall, the friend I'd always wanted, the sister I'd never had.

I imagined us whispering and giggling together, sharing books and games and dolls, telling each other secrets. We'd sleep in the same room and talk to each other in the dark. We'd go for long walks in the country. She'd show me her favorite thingsâa creek that swirled over white pebbles, lily pads in a pond, a bird's nest, butterflies, a tree with branches low enough to sit on and read. Maybe we'd have a dog or a pony.

Suddenly the coach hit a bump with enough force to hurl me against the man beside me. He drew away and scowled, as if offended by my proximity. Brought back to the stuffy confines of reality, I let go of my daydream. Sophia would not be waiting for me at Crutchfield Hall. I would have no sister. Just James, delicate James, a brother who might not be well enough to play.

With a sigh, I reminded myself that I was a fortunate girl. With every turn of the coach's wheels, I was leaving Miss Medleycoate's Home for Orphan Girls farther and farther behind. Surely I'd be happier at Crutchfield Hall than I'd been with Miss Medleycoate.

A

S THE CITY SLOWLY FADED

away behind us, I caught fleeting glimpses of open countryside, green meadows rolling away toward distant hills, red-roofed villages marked by church steeples, cows and sheep under a cloudy sky much higher and wider than it looked in London. I felt very small, rather like an ant riding in a coach the size of a walnut shell.

After an hour or so, the sky darkened and the wind rose. Rain pelted the coach and streamed down the windows, making it impossible to see out.

We stopped several times to let passengers off and take more on. The rough fellow was replaced by a farmer who had nothing to say to anyone. The old lady was replaced by a young woman who blushed whenever anyone looked at her.

The coach grew stuffy, and the voices around me blended into a sort of soothing music. The jolts and bumps and lurches changed to a rocking motion, and I soon fell asleep.

I was startled awake by the large woman beside me. “Stir yourself, child. This is where you get off.”

“Crutchfield Hall,” the coachman bellowed from his seat above us. “Ain't there someone what wants to get out here?”

I scrambled to my feet and stepped outside. Wind and rain struck me with a force that almost knocked me down. Groggy with sleep, I gazed at empty fields bordered by a forest, bare and bleak on this dark January afternoon. In the distance, I saw a line of hills, their tops hidden by rain, but no house. Not even a barn or a shed.

Bewildered, I peered up at the coachman through the rain. “Where is the house, sir?”

Gesturing with his whip, he pointed to an ornate iron gate topped with fancy curlicues. “Follow the drive till you come to the house,” he said. “It's one or two mile, I reckon. A big old place with chimneys. Pity there's no one to meet you.”