Why We Broke Up (5 page)

“I don’t know any girls like you,” you said.

“What?”

“I said I don’t know any—”

“Like me how?”

You sighed and then smiled and then shrugged and then smiled. The mobile was silver stars and comets glittering in circles around your head like I’d knocked you silly in a cartoon. “Arty?” you guessed.

I stood right in front of you. “I’m not arty,” I said. “Jean Sabinger is arty. Colleen Pale is arty.”

“They’re freaks,” you said. “Wait, are they friends of yours?”

“Because then they’re not freaks?”

“Then I’m sorry I said it is all,” you said. “Maybe smart is what I mean. Like, the other night you didn’t even know we’d lost the game. Usually, I thought everybody knows.”

“I didn’t even know there was a game.”

“And a movie like that.” You shook your head and made a weird breath. “If Trev knew I saw that, he’d think, I don’t know what he’d think. Those movies are gay, no offense about your friend Al.”

“Al’s not gay,” I said.

“The dude made a cake.”

“

I

made that.”

“You? No offense but it was awful.”

“The whole point,” I said, “is that it was supposed to be

bitter

, awful like a Bitter Sixteen party, instead of sweet.”

“Nobody ate it, no offense.”

“Stop saying no offense,” I said, “when you say offensive things. It’s not a free pass.”

You tilted your head at me, Ed, like a dim puppy wondering why the newspaper’s on the floor. At the time it was cute. “Are you mad at me?” you asked.

“No, not mad,” I said.

“You see, that’s another thing. I can’t tell. You’re a different girl than usual, no offense Min, oops, sorry.”

“What are the other girls like,” I said, “when they get mad?”

You sighed and handled your hair like it was a baseball cap you wanted to turn around. “Well, they don’t kiss me like we were. I mean, they don’t anyway, but then they stop when they’re mad and won’t talk and fold their arms, like a pouty thing, stand with their friends.”

“And what do you do?”

“Get them flowers.”

“That’s expensive.”

“Yeah, well, that’s another thing. They wouldn’t have bought the tickets like you did, for the movie. I pay for

everything, or else we have a fight and I get them flowers again.”

I liked, I admit, that we didn’t pretend there hadn’t been other girls. There was always a girl on you in the halls at school, like they came free with a backpack. “Where do you buy them?”

“Willows, over by school, or Garden of Earthly Delights if the Willows stuff isn’t fresh.”

“Fresh flowers, you’re talking about, and you think Al is gay.”

You blushed, a dashing red on both cheeks like I’d slapped you around. “This is what I mean,” you said. “You’re smart, you talk smart.”

“You don’t like the way I talk?”

“I’ve just never heard it before,” you said. “It’s like a new—like for instance a spicy food or something. Like, let’s try food from Whatever-stan.”

“I see.”

“And then you like it,” you said. “Usually. When you try it, you don’t want the—the other girls.”

“What do the other girls talk like?”

“Not a lot,” you said. “Usually I guess I’m talking.”

“Basketball. Layups.”

“Not just, but yeah, or practice, or Coach, if we’re gonna win next week.”

I looked at you. Ed, you were goddamn beautiful that

day and, you’re making me tear up in the truck right now, every other one, too. Weekends and weekdays, when you knew I was looking and when you didn’t even guess I was alive. Even with shiny stars bothering your head it was beautiful. “Basketball is boring,” I said.

“Wow,” you said.

“That’s another different thing?”

“I don’t like that one,” you said. “You never even went to a game, I bet.”

“Boys throwing a ball around and bouncing it,” I said, “right?”

“And old movies are boring and corny,” you said.

“You loved

Greta in the Wild

! I know you did!” And I know you did.

“I’m playing Friday,” you said.

“And I sit in the stands and watch you win and all the cheerleaders scream for you and I wait for you to come out of the locker room standing by myself for a bonfire party full of strangers?”

“I’ll take care of you,” you said quietly. You reached out and brushed my hair, my ear.

“Because I’d be,” I said, “you know, your date.”

“If you were with me after the game, it would be more like girlfriend.”

“Girlfriend,” I said. It was like trying on shoes.

“That’s what people would think, and say it.”

“They’d think Ed Slaterton was with that arty girl.”

“I’m the co-captain,” you said, like there was some way someone at school could not know that. “You’d be whatever I told them.”

“Which would be what, arty?”

“Smart.”

“Just smart?”

You shook your head. “The whole thing of what I’ve been trying,” you said, “is that you’re different, and you keep asking about the other girls, but what I mean is that I don’t think about them, because of the way you are.”

I stepped closer. “Say that one more time.” You grinned. “But I said it so lousy.”

What every girl wants to say to every boy. “Say it,” I said, “so I know what you’re saying.”

“Buy something,” said the first hag, “or get the hell out of my store.”

“We’re

browsing

,” you said, pretending to look at a lunch box.

“Five minutes, lovebirds.”

I remembered to look at the Dream door. “Did we miss her?”

“No,” you said. “I’ve kept an eye out.”

“I bet this is another thing you never do.”

You laughed. “No, I follow old movie stars most weekends.”

“I just want to know where she lives,” I said. I felt Lottie Carson’s birthday, the back of the lobby card, sparking in my purse, a secret plan.

“It’s fine,” you said. “It’s fun, something. But what will we do when we get there?”

“We’ll find out,” I said. “Maybe it’ll be like

Report from Istanbul

, where Jules Gelsen finds that underground room full of—”

“What is the old movies, with you?”

“What do you mean?”

“What do you mean what do I mean? You talk about old movies with everything. You’re thinking about one now probably, I bet.”

It was true: the last long shot of

Rosa’s Life of Crime

, another Gelsen vehicle. “Well, I want to be a director.”

“Really? Wow. Like Brad Heckerton?”

“No, like a

good

one,” I said. “Why, what did you think?”

“I didn’t really think,” you said.

“And what are you going to be?”

You blinked. “Winner of state finals, I hope.”

“And then?”

“Then a big party and college wherever they take me, and then I’ll find out when I get there.”

“Two minutes!”

“OK, OK.” You rummaged in a bin of rubber snakes, look busy look busy. “I should get you something.”

I frowned. “Everything’s ugly.”

“We’ll find something, it’ll kill time. What’s good for a director?”

You interviewed me down through the aisles. Masks for actors? No. Pinwheels for background scenes? No. Naughty board games for the party after the awards ceremony? Shut

up

.

“Here’s a camera,” you said. “There we go.”

“It’s a pinhole camera.”

“I don’t know what that is.”

“It’s cardboard.” I didn’t tell you that I didn’t know what it is either, just read it on the side of the thing. Or, until now, the truth of it, that I knew of course, of course I knew it, that there was a game and that you’d lost that night I met you in Al’s yard. But you seemed to like, I think, I hoped back then, that I was different.

“Cardboard, so what, I bet you don’t even have a camera.”

“Directors don’t do the cameras. That’s for the DP.”

“Oh right, the DP, I almost forgot.”

“You don’t know what a DP is.”

Three of your fingers gave me a jumpy tickle, right in the belly, where the butterflies lived. “Don’t start with me. Alley-oops, technical fouls, I have a dictionary of basketball in my head, and you don’t know any of it. I’m buying you this camera.”

“I bet you can’t even take real pictures with that.”

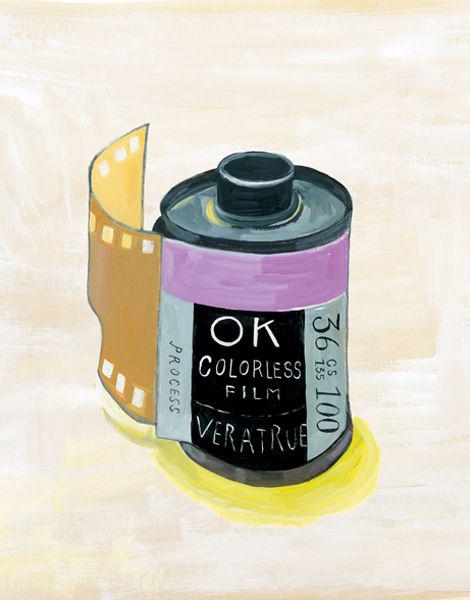

“It comes with film, it says.”

“It’s cardboard. The pictures wouldn’t come out right.”

“It’ll be, what’s the French word? For weirdo movies?”

“What?”

“There’s a, you know, an official descriptive phrase.”

“Classic films.”

“No, no, not gay ones like your friend. Like, really, really weird ones.”

“Al is not gay.”

“OK, but what is it? It’s French.”

“He had a girlfriend last year.”

“OK, OK.”

“She lives in LA. He met her at a summer thing he did.”

“OK, I believe you. Girl in LA.”

“And I don’t know what French thing you mean.”

“It’s for super-weird films, like oh no, she’s falling up the staircase inside somebody’s eye.”

“How would you know, anyway, if there was some film thing?”

“My sister,” you said. “She was almost a film major. She goes to State. You should talk to her, actually. You remind me, a little bit—”

“This is like hanging out with your sister?”

“Wow, this is another time when I can’t tell if you’re mad.”

“Better buy me flowers just in case.”

“OK, you’re not mad.”

“Out!” shrieked the second twin like a bossy curse.

“Ring this up,” you said, and tossed her the camera for her to catch. And here it is back at you, Ed. I could see the little arrogance there, from co-captaining, how it really could be

whatever you told them

, like you said. Girlfriend, maybe. “Ring this up and leave us alone.”

“I don’t have to put up with this,” she snarled. “Nine fifty.”

You gave her a bill from your pocket. “Don’t be that way. You know I love you best.”

That was the first time I saw that part, too. The hag melted into a fluttery puddle and smiled for the first time since the Paleozoic era. You winked, took the change. I should have seen it, Ed, as a sign that you were unreliable. Instead I saw it as a sign of charming, which is why I didn’t break it off right then and there, like I should have and wish wish wish I did. Instead I stayed out late with you on a bus and the stranger streets of a lost, far neighborhood where Lottie Carson was hiding out in a house with a garden full of statues making shadows in the dark. Instead I just kissed your cheek for a thank-you note, and we walked out opening the package and reading the instructions together for how to do it. It’s easy, it was easy, too easy to do this.

Avant-garde

was the term you were thinking of, I learned from

When the Lights Go Down: A Short Illustrated History of Film

, but we didn’t know that

when we had this. There were a million things, everything, I didn’t know. I was stupid, the official descriptive phrase for happy. I took this thing I’m giving you back, this thing you gave me as the star we were waiting for finally emerged.

“It’s opening!”

“Where?”

“No, the door!”

“What?”

“Across the street! It’s her! She’s leaving!”

“OK, let me open it.”

“Hurry!”

“Be quiet about it, Min.”

“But this is the moment.”

“OK, let me read the directions.”

“No time. She’s putting on gloves. Act normal. Take the

picture. It’s the only way we can know if it’s her.”

“OK, OK,

Wind film tight with knob A

.”

“Ed, she’s going.”

“Wait.” Laughing. “Tell her to wait.”

“What, wait, we think you’re a movie star and want to take your picture to be sure? I’ll do it, give it to me.”

“Min.”

“It’s mine anyway, you bought it for me.”

“Yeah, but—”

“You don’t think girls can work a camera?”

“I think you’re holding it upside down.”

Ten steps down the block, laughing more.

“OK,

now

. She’s going around the corner.”

“Hold subject in frame—”

“Open the thing.”

“How?”

“Give it back.”

“Oh, like this.

Now

.

There

. Then what? Wait. OK, yes.”

“Yes?”

“I think so. Something clicked.”

“Listen to you,

something clicked

. Is this how you’ll be when you’re directing a movie?”

“I’ll order someone else to do it. Some washed-up basketball player.”

“Stop.”

“OK, OK, then you wind it again? Right?”

“Um—”

“Come on, you’re good at

maaath

.”

“Stop it, and this isn’t math.”

“I’m taking another. There, at the bus stop.”

“Not so loud.”

“And another. OK, your turn.”

“My turn?”

“Your turn, Ed. Take it. Take some.”

“OK, OK. How many are there?”

“Take as many as we can. Then we’ll get them developed and then we’ll see.”

But we never did, did we? Here it is undeveloped, a roll of film with all its mysteries locked up. I never took it anyplace, just left it waiting in a drawer dreaming of stars. That was our time, to see if Lottie Carson was who we thought she was, all those shots we took, cracking up, kissing with our mouths open, laughing, but we never finished it. We thought we had time, running after her, jumping on the bus and trying to glimpse her dimple through the tired nurses arguing in scrubs and the moms on the phone with the groceries in the laps of the kids in the strollers. We hid behind mailboxes and lampposts half a block away as she kept moving through her neighborhood, where I’d never been, the sky getting dark on only the first date, thinking all the while we’d develop it later. We searched her mailbox,

Lottie Carson

on the envelope we hoped, you sprinting to trespass on her

worn and ornate porch, perfect for her, while I waited with my hands on the fence watching you bound your way there and back. You clambered there in five swift secs, over the iron wrought spikes cooling my palms in the dusk, quick quick quick through the garden with the whatnot of gnomes and milkmaids and toadstools and Virgin Marys all outwitted like the opposing team. You flew your way through all those stone silent statues, and if I could I’d thunk them all at your goddamn doorstep, as noisy as you were quiet, as furious as we were giggly, as cold and scornful as I was breathless and hot watching you cat burglar for evidence and come back shrugging and empty-handed so we still didn’t know, we still couldn’t be sure, not until everything was developed. Those thick kisses on the long bus home at night with nobody but us leaned out on the last row of seats and the driver with his eyes on the road

knowing it was none of his business, and kissing more at the bus stop when we parted from that date, and the shout of you moving crisscross away from me after I wouldn’t let you walk me home and have my mom bullet you all over the sidewalk from asking where in the world I had been. “See you Monday!” you called out, like you’d just figured out the days of the week. We thought we had time. I waved but couldn’t answer, because I was finally letting myself grin as wide as I’d wanted all afternoon, all evening, every sec of every minute with you, Ed. Shit, I guess I already loved you then. Doomed like a wineglass knowing it’ll get dropped someday, shoes that’ll be scuffed in no time, the new shirt you’ll soon enough muck up filthy. Al probably heard it in my voice when I called him, waking him because it was so late, then telling him never mind, forget it, sorry I woke you, go to bed, no I’m fine, I’m tired too, try you tomorrow, when he said he had no opinion. Already. First date, what could I do with my stupid self and the thrill of

see you Monday

? thinking there was time, plenty of time to see what pictures we’d made? But we never developed them. Undeveloped, the whole thing, tossed into a box before we really had a chance to know what we had, and that’s why we broke up.