Why We Broke Up (7 page)

Because the day, it was school. It was the bells too loud or rattly in broken speakers that would never get fixed. It was the bad floors squeaky and footprinted, and the bang of lockers. It was writing my name in the upper right-hand corner of the paper or Mr. Nelson would automatically deduct five points, and in the upper left-hand corner of the paper or Mr. Peters would deduct three. It was the pen just giving up midway and scratching invisible ink scars on the paper or suiciding to leak on my hand, and trying to remember if I’d touched my face recently and am I a ballpoint coal miner on my cheeks and chin. It was boys in a fight by the garbage cans for whatever reason, not my friends, not my crowd, my old locker partner crying about it on the bench I sat on freshman year with a gang I barely see anymore. Quizzes, pop quizzes, switching identities during attendance when there’s a sub, anything to pass time, more bells. It was the principal on the intercom, two whole minutes of ambient hum and shuffling, and then a very clear “That’s on, Dave” and it clicking off. It was a table selling croissants for French Club knocked over by Billy Keager like always, and the strawberry jam a sticky stain on the ground for three days before anyone cleaned it. Old trophies in a box, a plaque with this year’s names waiting to be filled in on the tag, blank and coffin-shaped. It was the

deep daydream and waking up with a teacher wanting an answer and refusing to repeat the question. Another bell, the announcement “ignore that bell” and Nelson scowling “He said

ignore

it” to people zipping backpacks. It was the paperwork in homeroom, stapled together wrong so everyone has to rotate them to fill them out. It was the bullshit and the tryouts for the school play, the banners with the big game Friday and then the big banner stolen and the announcement to rat someone out if anyone knew anything. It was Jenn and Tim breaking up, Skyler getting his car taken away, the rumor that Angela was pregnant but then the counter-rumor, no, it’s the flu, everyone throws up with the flu. It was the days the sun wasn’t even trying to get out of the clouds and be nice for once in its starry life. It was wet grass, damp hems, the wrong socks I forgot to throw out and so now found myself wearing, the sneaky leaf falling from my hair where it had nested for hours to surely someone’s delight. Serena getting her period and not having anything for it like always, scrounging from girls she didn’t even know in the bathrooms during second. Big game Friday, go Beavers, beat them Beavers, the dirty joke so boring to everyone but freshmen and Kyle Hapley. Choir tryouts, three girls selling knitting to help people in a hurricane, it was the library having nothing to offer no matter what needed looking up. It was fifth period, sixth, seventh, clock-watching and cheating on tests just because why not. It was suddenly

being hungry, tired, hot, furious, so unbelievably startling sad. Fourth period, how could it be only fourth, is what it was. Hester Prynne, Agamemnon, John Quincy Adams, distance times rate equals something, lowest common whatever, the radius, the metaphor, the free market. Someone’s red sweater, someone’s open folder, it was wondering how someone could lose a shoe, just one shoe, and not see it when it was hopeful on the windowsill for weeks. Call this number on the bulletin board, call if you’ve been abused, if you want to kill yourself, if you want to go to Austria this summer with these other losers in the picture. It was

STRIVE!

in bad letters on a faded background,

WET PAINT

on a dry floor, big game Friday, we need your spirit, give us your spirit. Locker combinations, vending machines, hooking up, cutting class, the secrets of smoking and headphones and rum in a soda bottle with mints to cover the breath, that one sickly boy with thick glasses and an electronic wheelchair, thank God I’m not him, or the neck brace, or the rash or the orthodontics or that drunk dad who showed up at a dance to hit her across the face, or that poor creature who somebody needs to tell

You smell, fix it, or it will never, never, never will it get better for you

. The days were all day every day, get a grade, take a note, put something on, put somebody down, cut open a frog and see if it’s like this picture of a frog cut open. But at night, the nights were you, finally on the phone with you, Ed, my happy thing, the best part.

The first time I called your number it was like the first time anyone had called anyone, Alexander Graham Whatsit, married to Jessica Curtain in the very dull movie, frowning over his staticky attempts for months of montage before finally managing to utter his magic sentence across the wire. Do you know what it was, Ed?

“Hello?” Damn it, it was your sister. How could this be the best number?

“Um, hi.”

“Hi.”

“Could I speak to Ed?”

“May I ask who’s calling?”

Oh, why did she have to do that, is what I thought, picking at my bedspread. “A friend,” I said, stupid shy.

“A friend?”

I closed my eyes. “Yes.”

There was an empty, buzzy moment and I heard Joan, though I didn’t know Joan yet, exhale and debate whether to question me further, while I thought, I could hang up now, like a thief in the night in

Like a Thief in the Night

.

“Hold on,” she said, and then a few secs, hum and clatter, your voice distant saying “What?” and Joan’s mocking, “Ed, do you have any friends? Because this girl said—”

“Shut up,” you said, very close, and then “Hello?”

“Hey.”

“Hey. Um, who—”

“Sorry, it’s Min.”

“Min, hey, I didn’t recognize your voice.”

“Yeah.”

“Hold on, I’m moving to another room because

Joanie’s just standing here!

”

“OK.”

Your sister saying something something, running water. “They’re

my

dishes,” you said to her. Something something. “She’s a

friend

of mine.” Something something. “I don’t know.” Something. “Nothing.”

I kept waiting.

Mr. Watson

, is the first thing the inventor said, miraculously from another room.

Come here—I want to see you

. “Hey, sorry.”

“It’s OK.”

“My sister.”

“Yeah.”

“She’s—well, you’ll meet her.”

“OK.”

“So—”

“Um, how was practice?”

“Fine. Glenn was kind of a dick, but that’s usual.”

“Oh.”

“How was—what is it that you do, after school?”

“Coffee.”

“Oh.”

“With Al. You know, hanging out. Lauren was there too.”

“OK, how was it?”

Ed, it was wonderful. To stutter through it with you or even stop stuttering and say nothing, was so lucky and soft, better talk than mile-a-minute with anyone. After a few minutes we’d stop rattling, we’d adjust, we’d settle in, and the conversation would speed into the night. Sometimes it was just laughing at the comparing of favorites, I love that flavor, that color’s cool, that album sucks, I’ve never seen that show, she’s awesome, he’s an idiot, you must be kidding, no way mine’s better, safe and hilarious like tickling. Sometimes it was stories we told, taking turns and encouraging, it’s not boring, it’s OK, I heard you, I hear you, you don’t have to say it, you can say it again, I’ve never told this to anyone, I won’t tell anyone else. You told me that time with your grand-father in the lobby. I told you that time with my mother and the red light. You told me that time with your sister and the locked door, and I told you that time with my old friend and the wrong ride. That time after the party, that time before the dance. That time at camp, on vacation, in the yard, down the street, inside that room I’ll never see again, that time with Dad, that time on the bus, that other time with Dad, that weird time at the place I already told you in the other story about that other time, the times linking up like snowflakes into a blizzard we made ourselves in a favorite winter. Ed, it was everything, those nights on the phone, everything we said until late became later and then later and

very late and finally to go to bed with my ear warm and worn and red from holding the phone close close close so as not to miss a word of what it was, because who cared how tired I was in the humdrum slave drive of our days without each other. I’d ruin any day, all my days, for those long nights with you, and I did. But that’s why right there it was doomed. We couldn’t only have the magic nights buzzing through the wires. We had to have the days, too, the bright impatient days spoiling everything with their unavoidable schedules, their mandatory times that don’t overlap, their loyal friends who don’t get along, the unforgiven travesties torn from the wall no matter what promises are uttered past midnight, and that’s why we broke up.

This is what I’m talking about, Ed:

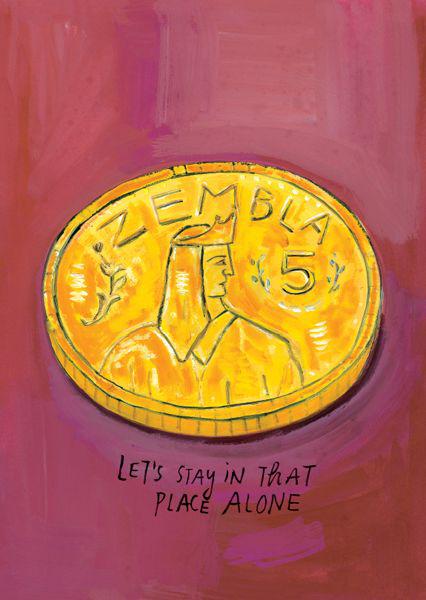

the truth of it. Look at this coin. Where is it from? What prime minister, whose king is that? Somewhere in the world they take this as money, but it wasn’t that day after school at Cheese Parlor.

We’d agreed, with more debate and diplomacy than that Nigel Krath’s seven-hour miniseries on Cardinal Richelieu, that we’d have an early dinner or a post-coffee, post-practice snack or whatever you call it when it’s sunset and you’re really supposed to be home but instead you’re having waffle-iron grilled cheeses and scalding watery tomato soup at a place of neutral territory. They were tired

of not meeting you, even though it hadn’t been any time at all. They thought, all of them, Jordan and Lauren, except Al because he had no opinion, that I was hiding you. Or was I ashamed of my friends? Was that it, Min? I said you had practice and they said that was no excuse and I said of course it was and then Lauren said maybe if we didn’t invite you, like with Al’s party, maybe then you’d show up, so I said OK, OK, OK, OK, shut up, OK, Tuesday after your practice, after coffee at Federico’s, let’s go to Cheese Parlor, which is centrally located and equally despised by everyone, and then I asked you and you said sure, sounds good. I sat in a booth with them and waited. The booths crinkled and the place mats suggested we quiz each other with cheese facts.

“Hey, Min, true or false, parmesan was invented in 1987?”

I took my finger out of my gnawing mouth and gave Jordan a strong flick. “You’re going to be nice to him, right?”

“We’re always nice.”

“No, you never are,” I said, “and I love you for it, sometimes, mostly, but not today.”

“If he’s going to be your whatever he’s going to be,” Lauren said, “then he should see us as God supposedly made us, in our natural environment, with our usual—”

“We never come here,” Al said.

“We already argued this out,” I reminded him.

Lauren sighed. “All I mean is that if we’re all going to hang together—”

“Hang together?”

“Maybe we won’t,” Jordan said. “Maybe it won’t be that way. Maybe we’ll just see each other at the wedding, or—”

“

Stop

it.”

“Doesn’t he have a sister?” Lauren said. “Think of both of us dressed together for the bridal party! In

plum

!”

“I knew it would be like this. I should tell him not to come.”

“Maybe he’s already scared of us and won’t show,” Jordan said.

“Yeah,” Lauren said, “like maybe he didn’t want Min’s number and maybe he wasn’t going to call her and maybe they’re not really—”

I put my head down on the table and blinked at a picture of brie.

“Don’t look now,” Al murmured, “but there’s a ball of sweat by the entrance.”

It’s true you looked particularly, wetly athletic. I stood up and kissed you, feeling like the scene in

The Big Vault

where Tom D’Allesandro doesn’t know Dodie Kitt is being held hostage right under his nose. “Hey,” you said, and then looked down at my friends. “And hey.”

“Hey,” they all goddamn said.

You slid in. “I haven’t been here in forever,” you said.

“Last year I went with somebody who liked the whatsit, the hot cheese soup.”

“Fondue,” Jordan said.

“Was that Karen?” Lauren said. “With the braids and the cast on her ankle?”

You were blinking. “That was Carol,” you said, “and it wasn’t the fondue. It was the hot cheese soup.” You pointed to

HOT CHEESE SOUP

on the menu and it got, just for a sec, quiet as death.

“We always get the special,” Al said.

“I’ll have the special, then,” you said. “And Al, don’t let me forget.” You tapped your bag. “Jon Hansen told me to give you a folder for the lit project.”

Lauren swiveled to Al. “You have lit with Jonathan Hansen?”

Al shook his head and you took a long, long gulp of ice water. I watched your throat and wanted it, every word you ever said, all to myself. “His girlfriend,” you explained finally. “Joanna Something-ton. Though, and don’t tell anyone, not for long. Hey, you know what I remember?”

“That Joanna Farmington’s a friend of mine?” Lauren said.

You shook your head and waved to the waiter. “Jukebox,” you said. “They have a good jukebox here.” You heaved your bag onto the table, found your wallet, frowned at the bills. “Somebody have change?” you said, and then

reached across for Lauren’s purse. I don’t know a thing about sports, but I could feel the strike ones, strike twos, strike threes whizzing over your head. You undid the zipper and moved things around. My eyes met Al trying not to meet my eyes. The person besides Lauren who is allowed into Lauren’s purse is whoever finds her dead in a ditch and is looking for identification. A tampon peeked out the top and then you found her change purse and smiled and unsnapped it and dumped the coins into your hand. “We all want the special,” you told the waiter, and then you stood up and strode to the jukebox, leaving me alone at a shell-shocked table.