Why We Broke Up (8 page)

Lauren was staring at her purse like it was dead in the road. “Jesus Christ and his biological Father.”

“As your mother would say,” Jordan added.

“They do that,” I said desperately, “with their friends, share money like that.”

“

They do that?

” Lauren said. “What is this, a nature special? Are they hyenas?”

“Let’s hope they don’t mate for life,” Jordan muttered.

Al just looked at me, like he’d jump on his horse, fire his revolver, open the escape hatch, but only on my say-so. I didn’t say-so. You came back and grinned at everybody and, strike billion, Tommy Fox started to play. Ed, I can’t even explain, but Tommy Fox, I never told you, is a joke to us, not even a good joke because Tommy Fox is too easy a joke.

You grinned again and spun this coin on the table, sputter spin sputter spin, while we all stared.

“This didn’t work,” you said, pointing to the middle of the table, the no-man’s-land where this useless thing was spinning.

“You don’t say,” Lauren said.

“I love the guitars on this,” you said, sitting down and throwing your arm around me. I leaned against it, Ed, your arm felt good even with Tommy Fox in the air.

“He’s joking,” I said. Desperately again. I hoped and lied, Ed, for you. This clattered to a stop and I pocketed it while we ate and stuttered and stumbled and paid and left. Your eyes were so sweet, walking me to the bus while they walked the other way. I watched them huddled together and already laughing. Oh, wherever it works, Ed, I thought with your hand on my hip and the not-fitting coin in my pocket. Wherever it’s good, whatever strange faraway land, let’s go there, let’s stay in that place alone.

Look close

and you’ll see the hair or two that came with the rubber band when you ripped it off me. Who would do such a thing? What kind of man, Ed? I actually didn’t mind at the time.

Our first time where you live, where you’ll read this, heartbroken. Walking home with you for the first time, the bus together, after watching you practice. I was worn out, tired from not having my usual Federico’s coffee. Tired from being bored, really, in the bleachers while you practiced free throws with the coach blowing his shrieky whistle with the advice of

Try to get it in the basket more

. I actually dozed for a

sec on your arm on the bus, and when I woke up you were looking wistful at me. You were sweaty and a mess. I felt my breath bad from sleeping even for that minute, the way it does. The sun came through the smeared and messed-up transit windows. You said you liked watching me sleep. You said you wished you could see me wake up in the morning. For the first time, not for the first time if I’m going to tell the real truth, I tried to think of someplace, someplace extraordinary, where that would happen. The whole school knows that if we make state finals, everyone from the team stays in a hotel and Coach looks the other way, but we never made it that far.

When we walked through the back door, you called out “Joanie, I’m home!” and I heard someone, “You know the rules—don’t talk to me until you shower.”

“Hang out with my sister for a sec?” you asked me.

“I don’t know her,” I said, in a living room with all the sofa cushions pushed together on the floor like dominoes.

“She’s nice,” you said. “I told you about her. Talk about movies you like. Don’t call her Joanie.”

“But

you

called her Joanie,” I said, but you were off bounding up the stairs. The sofa gutted of cushions, stacks of distant magazines, a teacup, the whole room unsupervised. Through the doorway was music I instantly loved but couldn’t really pin down. It sounded like jazz but not embarrassing.

I walked toward the tune, and Joan was dancing in the kitchen with her eyes closed, partnered with a wooden spoon. Chopped piles were everywhere on the counter. Ed, your sister is beautiful amazing, tell her that from me.

“What is this?”

“What?” She wasn’t surprised or anything.

“Sorry. I like the music.”

“You shouldn’t be sorry to like this music. Hawk Davies,

The Feeling

.”

“What?”

“

You either have the feeling or you don’t

. You haven’t heard of Hawk Davies?”

“Oh yeah, Hawk Davies.”

“Stop it. It’s cool you haven’t. Ah, to be young again.”

She turned it up and kept dancing. I could, I thought, maybe should go back into the living room. “You’re the girl from the phone the other night.”

“Yeah,” I owned up.

“A

friend

,” she recited. “What’s your name,

a friend

?”

I told her it was Min, short for etc.

“That’s quite a speech,” she said. “I’m Joan. I like Joanie like you like Minnie.”

“Ed told me, yeah.”

“Don’t trust the word of a boy who’s sweaty filthy at the end of

every goddamn day take a goddamn shower!

”

She shouted the last of this at the ceiling.

Stomp stomp

stomp

, rattle of the kitchen light fixture, and upstairs the shower went on. Joan grinned and then looked me over on the way to go back to chopping. “You know, I hope you don’t mind, and no offense, but you don’t look like a sidelines girl.”

“No?”

“You’re more—”

chop chop

she searched for the

chop chop

word. Behind her was a rack of knives. If she said

arty

—

“—interesting.”

I made myself not smile.

Thank you

didn’t seem right for it. “Well, today I was a sidelines girl,” I said. “I guess.”

“Hey!”

She perked up bright and sarcastic, her eyes wide and the knife up like a flagpole.

“Let’s watch boys practice playing a game so we can watch them play the game later!”

“You don’t like basketball?”

“Sorry, did you like it? How was it, watching him?”

“Boring,” I said instantly. Drum solo on the album.

“Dating my brother,” she said, with a shake of her head. She stepped to the stove and stirred and licked the spoon, something tomato. “You’ll be a widow, a basketball widow, bored out of your mind while he dribbles all over the world. So you don’t like basketball—”

It was already true, Ed. I had already wondered if it was OK to do homework or just read while you practiced. But nobody else was. The other girlfriends didn’t talk much among themselves and never to me, just looking my way

like the waiter had brought the wrong salad dressing. But it was so elegant and worthwhile to have you wave, and the sweat on your back when you all divided into shirts and skins.

“—and don’t know music, what do you like?”

“Movies,” I said. “Film. I want to be a director.”

Song stopped, next one began. Joan looked at me for some reason like I’d socked her. “I heard,” I said. “Ed told me you were studying film. At State?”

She sighed, put her hands on her hips. “For a little bit. But I had to change. Get more practical.”

“Why?”

The shower turned off. “Mom got sick,” she said, flicking her chin in the direction of the far bedroom, and there’s something that never came up with you, not on any night on the phone.

But I’m good at changing the subject. “What are you making?”

“Vegetarian Swedish meatballs.”

“I cook too, with Al.”

“Al?”

“My friend. Can I help you?”

“All my

life

, Min, for

eons

I have waited for someone to ask that question. I hope you agree that aprons are useless, but here, take this.” She went to the door and fiddled at the knob for a sec before dropping it into my hand. Rubber

bands, you kept them there, every doorknob in the house.

“Um.”

“Put your hair up, Min. The secret ingredient is not

your

hair

.”

“Then how do you make vegetarian Swedish meatballs? Fish?”

“Fish is meat, Min. Oyster mushrooms, cashews, scallions, paprika I need to find, parsley, grated root vegetables, which you can grate. The sauce I did already, that’s bubbling. Sound good?”

“Yes, but it’s not really very Swedish.”

Joan smiled. “It’s not really very

anything

,” she admitted. “I’m just trying something here, you know?

Attempting

is what I’m doing.”

“Attempted meatballs, you could call it instead,” I said, with my hair up.

She handed me the grater. “I like you,” she said. “Tell me if you want to borrow my old Film Studies books. And tell me if Ed treats you badly so I can fillet him,” so I guess you’re on a plate somewhere with lemon and whatnot, Ed. Instead you came downstairs with crazy hair and loose clothes, a T-shirt from a stadium show, bare feet, and shorts.

“Hi,” you said, and wrapped your arms around me. You gave me a kiss and took the rubber band,

ow

, out of my hair.

“Ed.”

“I like it better, no offense, it looks better down.”

“She needs it up,” Joan said.

“No, we’re hanging out,” you said.

“Yes, and cooking.”

“You could at least put on decent music.”

“Hawk Davies crushes Truthster like a grape. Go watch TV. Min’s helping me.”

You pouted to the fridge and grabbed milk to drink from the carton and then pour in a bowl for cereal. “You’re not my real mom,” you said, obviously an old joke.

Your beautiful sister took the rubber band out of your hand and dropped it into mine, a loose worm, lazy snake, wide-open lasso ready to rodeo something. “If I were your real mom,” she said.

“Yeah, yeah, strangled in the crib.” You snacked off to the living room, and Joan and I made the vegetarian Swedish meatballs, which turned out delicious and surprising. I told Al the recipe that night, and he said they sounded great and maybe we could make them Friday night or Saturday or Saturday night or even Sunday night, he could ask his dad for the night off from the shop, but I said no, I wasn’t going to be free all weekend, it was a busy weekend for me. My calendar was full, not that I have a calendar. You slumped stretched out on the cushions, what they were doing on the floor, with cereal and dumb TV I could see but not hear from the kitchen. Cooking with Joan like she was my sister too, kind of, simmering and warm and scented like pepper

and sweetness and smoke, dancing finally next to her. Hawk Davies giving me the feeling, giving everybody the feeling that afternoon in your kitchen. Letting my hair down with my hair up, in a rubber band from your doorknob, and your shirt riding up as you hung out on the floor, your shorts loose and low, the small of your back I’d watched all day.

Take it back, Ed. Take it all back.

I guess I

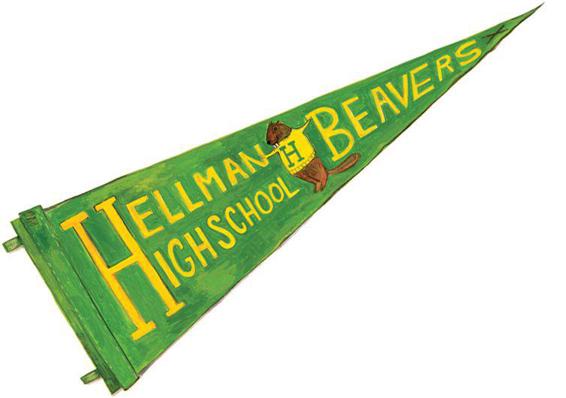

was supposed to put this up, I guess it should have hung over my bed in a crisscross diagonal like it was X-ing out anything else:

HELLMAN HIGH SCHOOL BEAVERS

. And I guess I could say the reason it never went anywhere was that the Beaver colors of yellow and green clashed with what is over my bed, the poster of my favorite movie in the world,

Never by Candlelight

, Theodora Sire’s eyebrows forever raised in the poster Al gave me last birthday that took him forever to find, like she wasn’t going to say anything but that what went on in my bedroom was inelegant and unworthy of me. I didn’t put it up, didn’t want it up, should have known then.

It might as well have said

HELLMAN HIGH SCHOOL ED’S NEW GIRLFRIEND

when I found it Friday staked in a slat in my locker, waving in the breeze of the stale vents like when the diplomats arrive in

Hotel Continental

. It took some wiggling to get it out, and I felt my flushy face grinning and fighting not to grin. Everybody knows that even though the pennants are always for sale on game days with the second-string cheerleaders assigned to hawk them desperate and smiley in the cafeteria, they’re only for freshmen and parents and any other clueless souls and for the girlfriends of the players who snitch them to give out like long-stemmed roses Friday morning. And people saw and worked it out. Jillian Beach had nothing flying at her locker, and enough people had gossiply seen me with you at practice that week after school to figure who my flag was from. The co-captain, must have been somewhere in the gasping, and Min Green. People must have asked Lauren, asked Al if it was true. They must have said

yeah

, just

yeah

, or maybe they said worse, I don’t like to think.