Will Eisner (18 page)

Authors: Michael Schumacher

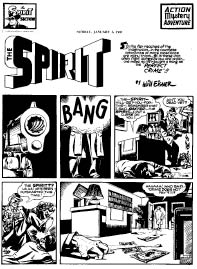

At a time when crime comics such as

Crime Does Not Pay

were reaching a height in popularity but were being scrutinized for their violent content, Eisner proved to be a master of combining action and violence without depicting the bloodshed. The opening page of this January 5, 1947

Spirit

, which includes an Eisner quip about the mounting criticism of such comics, is an example. (© Will Eisner Studios, Inc., courtesy of Denis Kitchen)

But in the end, Eisner’s work wasn’t immune from criticism, nor did it escape the notice of a would-be censor’s watchful eye. In his ceaseless attempts to present stories that would appeal to older readers, he’d test the boundaries of the day’s standards, risking an editor’s ire, pulling back if necessary, and starting over again. Any suggestion of sex, of course, was adult content, and Eisner had to be careful when dealing with the Spirit’s relationships with women. The Spirit was handsome, single, virile, athletic, intelligent, mysterious, and sexy—the type of man who just might turn a woman’s head. In the Spirit, Eisner had created a character who was constantly attracted to beautiful women, and as with James Bond two decades later, that attraction could be dangerous. His relationship with Ellen Dolan, everybody’s favorite girl next door, was chaste and playful—although in one story he did give her a spanking that raised a few eyebrows—but in his villainous femmes fatales, he was dealing with something entirely different.

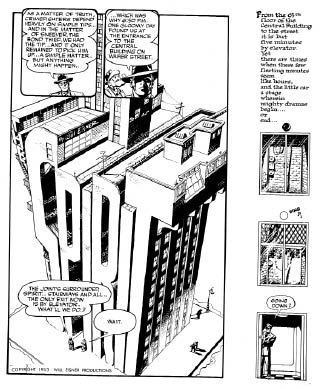

Rather than use a standard logo for his

Spirit

entries, Eisner preferred to work the title into a story’s artwork. This splash page from a June 26, 1949 story is one of Eisner’s most memorable. (© Will Eisner Studios, Inc., courtesy of Denis Kitchen)

Eisner had introduced these intriguing foils early in

The Spirit

’s history. They had catchy names—Black Queen, Sand Saref, Skinny Bones, Thorne Strand, Flaxen Weaver, Powder Pouf, Silk Satin, and, best known of the group, the indomitable P’Gell—and they had curvaceous forms, sharp minds, and past lives as mysterious as the Spirit’s. They were strongly independent and seductive. They traveled internationally, giving Eisner occasion to place his stories in exotic locations. Most important of all, they were the Spirit’s equals, capable of exposing his weaknesses and matching him in a battle of wits. In every respect, these women were more fully realized as characters than their male counterparts.

His femmes fatales, Eisner confessed, were precisely the kinds of women he himself found attractive.

“Every man who works in this field—whether he’s writing short stories or novels, working in this medium or doing paintings—responds to his personal ideal of what is an attractive woman,” he said. “I’m generally turned on by a very intelligent, self-contained, confident woman whose seduction represents a substantial action. As one writer once said, ‘To seduce the maid is not great trouble. But to seduce the duchess—that’s an accomplishment!’”

Each of these women attracted the Spirit in a different way. Sand Saref and Denny Colt had been childhood friends, and it’s clear that they would have been adult lovers if Colt’s uncle, a thief, hadn’t been unjustly accused of killing Saref’s father, a police officer pursuing him.

“I walked a tightrope with her,” Eisner said of Saref, who originally was cast in a

John Law

story, only to be recycled in a two-part

Spirit

episode when the proposed

John Law

comic book fell through. “I wanted her to be in command, tough and independent, yet I tried to get the reader to feel compassion for her, to hope that she might turn away from crime.” Happy endings, however, weren’t in the cards for her. “That wouldn’t have been true to Sand’s character. She’s too strong a character to change her life in an instant.”

The other femmes fatales were similarly strong characters. Silk Satin, a Katharine Hepburn look-alike, is also a reluctant criminal, a woman trapped by circumstance, deeply in love with the Spirit, and under other conditions, she might have wound up with him. Skinny Bones, a Lauren Bacall knockoff, works for the Mob, while Black Queen, the first of Eisner’s femmes fatales,

is

the Mob.

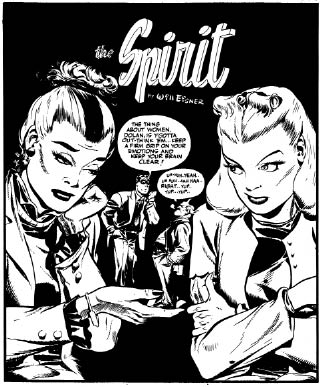

Eisner’s femmes fatales, one of his trademark

Spirit

features, were beautiful, intelligent, sexy—and potentially lethal. This January 23, 1949 splash page is an example of how Eisner tried to work humor into his story. (© Will Eisner Studios, Inc., courtesy of Denis Kitchen)

None, however, compared with P’Gell, the often married (and widowed), well-traveled villainess who appeared in more

Spirit

stories—seventeen in all—than any of these dangerous women. The ultimate foe, partly good but mostly naughty, P’Gell proved irresistible to the Spirit, who’s drawn to her repeatedly, only to barely escape with his life with each encounter.

“The stories with her were always special ones,” Eisner admitted. “I especially enjoyed these because it was always The Spirit’s wits against hers, and that’s an aspect of The Spirit that I’ve always enjoyed exploring—the way he can think his way through a situation.”

These seductive, pinup-perfect characters, more than any of their male counterparts, helped propel

The Spirit

into the adult market. Male villains such as the Octopus, Dr. Cobra, Mr. Carrion, and the Squid seemed as familiar and packaged as the villains in the superhero comics and required action, more than thought, for the Spirit to defeat them. Eisner not only recognized as much he enjoyed poking fun at men’s mistaken belief that they were the stronger sex. “The thing about women,” the Spirit says to Commissioner Dolan in a splash page for a Thorne Strand episode, “is y’gotta outthink them … Keep a firm grip on your emotions and keep your brain clear.”

The Spirit and Dolan’s perch? The palm of Thorne Strand’s hand.

On September 5, 1948, Eisner published a

Spirit

episode entitled “The Story of Gerhard Shnobble,” a seven-page story that, in time, would prove to be his most critically acclaimed and frequently reprinted work from the series. The story featured Eisner’s trademarks—a strong narrative, a memorable character, experimentation in form, interesting camera angles, and a powerful ending—and managed to do so with the Spirit being only an incidental presence in the story.

Of all his

Spirit

stories, this became Eisner’s personal favorite.

“When I did ‘Gerhard Shnobble,’” he told interviewer Tom Heintjes, “I found that I could take a simple theme and use it as a way of dealing with a philosophical point. The theme I was working with is that everyone, no matter how small they seem, has a moment of glory. I’m fascinated by the fact that the world has billions of people, each of whom does small things. And I’m convinced that small acts can have huge ramifications. I just can’t get out of my mind the belief that our existence is part of a larger scheme.”

Eisner would repeatedly return to this theme and expand upon it in his graphic novels, but “Gerhard Shnobble” stood out because of its combined intensity and brevity. This was clearly not kids’ play. In the past, Eisner had been able to disguise his own feelings in his characters, but as he admitted later, he put himself on the line in this fable about a little nebbish with the ability to fly.

“It was the first time that I was truly aware that I could do a story that I had great personal feelings about,” he said of the piece. “It proved to me that I could write something with a little more depth to it. Most of the stories I did up to this time were not as consciously personal as this.”

In the story, the title character discovers on his eighth birthday that he has the ability to fly—if he

believes

he can. His parents, through scolding and beatings, discourage him from ever showing the ability to others, and he literally blots it out of his mind. He proceeds through a terminally ordinary life as a figure on the fringes of failure, an invisible nerd barely scraping by, whose greatest achievement is a promotion to night watchman at a bank. The bank is burglarized and Shnobble is fired, reinforcing his feelings of isolation and uselessness. Thoroughly defeated, he walks the streets of New York until, through the wall of his depression, he remembers his unique ability. Determined to prove to the world that he is indeed special, he takes an elevator to the rooftop of a skyscraper, from which he proposes to drop and then soar over the people on the street below. Instead, he becomes the ultimate person at the wrong place at the wrong time: the bank robbers have been trapped on the roof of the same building, and the Spirit, called to the scene to apprehend them, winds up battling them just as Shnobble steps off the building and begins his flight. Shnobble is hit by stray gunfire, and rather than wow the crowd with his ability to fly, he falls to earth, another victim of senseless crime. In the story’s concluding panel, a narrator drives home Eisner’s point: “Do not weep for Shnobble … Rather shed a tear for all mankind … For not one person in the entire crowd that watched his body being carted away … knew or even suspected that on this day Gerhard Shnobble had flown.”

For all its fantastic drama, this Everyman’s fable was deeply personal for Eisner, traipsing back to the tenements of the Bronx, to Sam Eisner’s need (and failure) to prove his own artistic talent, to Will Eisner’s discouragement and eventual faith in his ability, to his inextricable obsession with struggle and with spiritual and physical triumph. The ghosts of the past hovered over this tale and informed it in subtle but important ways.

To add realism to his sequential art, Eisner inserted actual photographs of New York’s cityscape as backgrounds in two of the panels—a bold, experimental move that had engravers screaming and Eisner’s readers applauding. Once again, solving a problem had led to a memorable innovation.

The final page of “The Story of Gerhard Shnobble,” Eisner’s favorite

Spirit

story. (© Will Eisner Studios, Inc., courtesy of Denis Kitchen)

“I had been wanting to do something like that for a long time,” he said. “I wanted action against a real landscape, and this was a splendid opportunity for it because I needed city buildings. I simply got the photos from a file somewhere and put a screen on them, and just inserted them in the story.”