Will Eisner (16 page)

Authors: Michael Schumacher

“We weren’t getting along very well with each other at the time,” he shrugged.

For all their bickering about politics, art, or anything else that came to the forefront in their discussions, Feiffer and Eisner never reached a point where their differences interfered with their work—or, for that matter, their friendship. “Our fights were always collegial,” Feiffer recalled. “Never once did he pull rank on me. I was always amazed by what he let me get away with. It shows how close and tight the relationship was, that he let me do that parody. He had great generosity of soul.”

Feiffer was absent from Eisner’s studio for much of 1947 while he attended the Pratt Institute. He loved the storytelling aspects of the comic book trade, but his struggles with comic book art convinced him that with formal training, he might be better suited to a career in advertising art. Fortunately for those who eventually enjoyed his Pulitzer Prize–winning cartoons, children’s books, plays, and films made from his screenplays, this didn’t turn out to be the case.

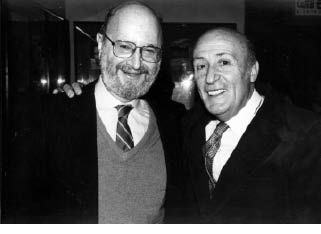

With Jules Feiffer in 1988. Eisner gave Feiffer his first illustration work when Feiffer was still a teenager, and then watched him blossom into a Pulitzer Prize–winning cartoonist. (Courtesy of Denis Kitchen)

By mid-1947, Eisner’s creativity was reaching another high-water mark. Much of his success could be credited to his small but supremely talented shop. Eisner had worked with gifted artists over the years, but the studio contributing to

The Spirit

from 1947 to 1949 was far and away his best group yet. When reflecting on the

Spirit

issues published during this period, Eisner reserved for these artists some of the highest praise he would ever bestow on collaborators. All were specialists in areas that Eisner wanted to improve.

Abe Kanegson, a Bronx native who attended the same high school as Jules Feiffer, did

The Spirit

’s lettering, as well as some backgrounds, from 1947 to 1950. A large, burly Russian Jew, Kanegson was, as Feiffer remembered, “the left intellectual of the office,” an opinionated presence with a heavy stutter that made his proclamations painfully slow to process. Eisner maintained that of all the letterers he employed over the years, Kanegson was one of the few who understood the nuances of lettering and who treated lettering as more than just a job. “Kanegson was brilliant,” Eisner said. “He added a dimension of quality that typesetting could never get. His lettering is clear and legible, and in addition it lends warmth to the visuals.”

Eisner used lettering to set tone or establish mood, and Kanegson’s range allowed him to use types of lettering not often seen in comics, like blackletter, to great effect. “To me, lettering contributes as much in the storytelling as the art itself,” he explained. “To my mind, there is no real border between the lettering and the artwork.”

André LeBlanc, who would go on to work on such features as

The Phantom

and

Rex Morgan, M.D.

, was skilled at drawing animals—something Eisner could not do well and a deficiency in the studio since Bob Powell’s departure. One of the period’s memorable stories, “Cromlech Was a Nature Boy,” in which Ebony befriends a boy capable of communicating with animals, would never have happened without LeBlanc’s contributions.

“There’s always been between André and myself a really good rapport creatively,” Eisner noted. “That’s strange, because his stuff does not concentrate on action. His work concentrates largely on strong draftsmanship and a warm quality of art. His animal drawings are marvelous, as are his depictions of children.”

The Cromlech story grew out of Eisner’s observations of a street poet and musician known as Moondog—“the first visible hippie,” as Eisner would describe him. Eisner would see him hanging around Forty-second and Broadway, selling a paper called the

Hobo News

, and from there he let his imagination roam. He penciled a rough splash page and showed it to LeBlanc.

“I said, ‘Let’s do a Nature Boy story,’ because there was a Nature Boy song that was built around Moondog,” Eisner said. “I roughed out the story idea and André took over … We passed it back and forth.”

Eisner’s willingness to let others tinker with his ideas—another personal trademark—led to some of his most extraordinary work during the 1947–1948 period, including adaptations of two stories Eisner had enjoyed in his youth: Ambrose Bierce’s 1894 horror story, “The Damned Thing,” and Edgar Allan Poe’s 1839 classic, “The Fall of the House of Usher.” Eisner’s love of adaptations dated back to his Fiction House days, although, ironically, he usually assigned adaptations to others. In his first studio, Jack Kirby had drawn

The Count of Monte Cristo

, and Dick Briefer had handled

The Hunchback of Notre Dame

. Eisner had adapted “Cinderella” and “Hansel and Gretel” in recent

Spirit

entries, with only marginal success. He assigned these two more recent adaptations to Jerry Grandenetti, a relatively new hire at the shop who’d expressed interest in doing a

Spirit

on his own.

“I was always faced with hiring somebody almost brand new in the field, who had basically good talents, but who was inexperienced,” Eisner said. “The assistant would go along working in the shop, and then very suddenly, he blossomed into a man of his own.

“Typically, the assistant began to make more demands, which is normal, which is acceptable. The assistant was working on my feature, but he wanted to stretch out, to break out of the so-called enslavement that he perceived working in my shop.”

Eisner had discovered Grandenetti while searching for a background man for

The Spirit

’s cityscapes. Grandenetti, ten years Eisner’s junior, was then working as a draftsman with a landscape architectural firm, but he wasn’t happy with the job. He wanted out, but he wasn’t sure if he wanted to go into comics, which appealed to him, or become an illustrator for a magazine such as the

Saturday Evening Post

or

Cosmopolitan

, which promised to be much more lucrative but was also cutthroat. He decided to give comics a try. He packed a portfolio with samples and headed up to Quality Comics, but instead of landing a job with Busy Arnold, he was referred to Eisner. He felt blessed to have been hired by someone of Eisner’s reputation and even more fortunate to be given a lot of freedom to learn on the job.

“I don’t think Bill ever pushed anybody,” he said, remembering the shop as being quiet and professional but easygoing. “He would let us do our thing, which was a tremendous break for me. I was dumped into the world of comics from the world of architecture, and here I was, trying to figure out how to do that. Bill wouldn’t tell me; I

did

it. Bill would literally write the story right onto the page itself, and then we’d take it from there.”

The two adaptations were almost entirely Grandenetti’s. Eisner, as always, supplied the direction, penciling and inking the splash page for “The Fall of the House of Usher,” which marked the Spirit’s sole appearance in the entry, and then laying out the rest of the story with rough penciling. The rest, with the exception of the Abe Kanegson’s lettering, was Grandenetti’s. The resulting story looked nothing like the typical Eisner

Spirit

, though his influence is felt throughout, especially in the camera angles.

The shop worked so efficiently that, in time, Eisner couldn’t remember the exact contribution each artist made to a given

Spirit

entry. This was especially true of his collaborations with Feiffer, which led to some interesting and occasionally testy discussions in later years, after Feiffer had established his reputation and interviewers asked about his work on

The Spirit

. One particular story, a 1949

Spirit

classic called “Ten Minutes,” brought out the possessiveness that each man felt about his own finer work.

The clever conceit of “Ten Minutes” was to tell a story in real time. “It will take you ten minutes to read this story,” a voice-over narrator informs the reader at the onset of “Ten Minutes.” “But these ten minutes that you will spend here are an eternity for one man. For they are the last ten minutes in Freddy’s life.”

Giving away a story’s ending up front takes a lot of moxie, but doing so before a seven-page comic book story posed the challenge of making a reader care about a character in very short order. To give the reader a sense of the passing time, Eisner placed a clock in the opening panel of each new page. In a more subtle move, the reader also sees two little girls playing a game with a ball on the sidewalk outside Freddy’s tenement building. The girls are running through the alphabet. The story opens with the letter “A,” and by the fifth page—six minutes into the story—they have reached the letter “R.”

The Spirit plays a marginal but important role in the story, appearing in the last minute of Freddy’s life. The rest is about a down-on-his-luck gambler trying desperately to find a way out of his dead-end life. In holding up a candy store run by a kindly neighborhood icon and unintentionally killing him, Freddy sets in motion the last few minutes of his life. By this point, the reader sees Freddy as an unlucky loser but not evil, and his violent end is both poignant and sad, underscoring how a very brief period of time can change the direction of a person’s life.

“That was mine,” Feiffer said of the story. “That was simply an autobiographical fantasy based on my Bronx upbringing. And the fat candy store man was based on a candy man that I remembered from my childhood.

I suppose what so interested me in that kind of approach was that I was living that sort of life in the East Bronx: painfully dull and painfully dismal, and painfully poor. Lower middle class; not poverty, but poor in spirit, certainly. And that one could take off from that vantage point and enter into all sorts of danger, which was fascinating.

Eisner, as Feiffer remembered, wrote Freddy’s death scene in the subway, but the rest was his creation.

Eisner, of course, had a different memory.

“The philosophy [of “Ten Minutes”] is essentially mine,” Eisner maintained, “as differentiated from Feiffer.

Feiffer to this day doesn’t think in terms of that kind of philosophical concept, like the ten minutes in a man’s life. You look at my body of work, you’ll see I always seem to build on that theme. On the other hand my dialogue isn’t as crisp and as sharp and sometimes as incisive as Feiffer’s is. Feiffer has—he always did have—an incredible ear for dialogue and in the way people talk, particularly. Now in the matter of this little girl bouncing a ball … Remember, too, that Feiffer and I have the same background, ten years apart. We both lived in the same area so we both came up and lived the same kind of childhood, except, perhaps, that his parents were half notch or a notch higher on the social scale than mine. So we would tend to say—probably, I might have said, “Hey, remember ‘A, my name is Alice; B, my name is—’” “Oh yeah,” he said, “I’ll do that.” He later included it in

Clifford

and so forth. But that doesn’t mean I should get credit for it.

According to Eisner, he generally came up for an idea for a story during his more reflective moments, such as when he was deep in thought while taking the train home from work, and he would then discuss the idea with Feiffer and the others working at the shop. Producing the story became a cooperative effort, from Eisner’s rough penciling to Feiffer’s dialogue balloons to Abe Kanegson’s lettering. The popularity of “Ten Minutes”—it became one of

The Spirit

’s most frequently reprinted stories—probably had more to do with the disagreement over authorship than anything.

In his memoir,

Backing into Forward

, Feiffer admitted that he intentionally mimicked Eisner when writing the Spirit stories and that “Ten Minutes,” like the others that he ghostwrote for the feature, was “really a Spirit story that was really a Jules story in Eisner drag.

While I was the writer on

The Spirit

, I was by no means its auteur. That was Eisner. Every scene I conceived, no matter how it turned out, started out as if I were he. Later, when I was throwing in more and more pieces of myself, nothing went in that didn’t exist comfortably with Eisner’s sensibility.

He and I would first talk story. I’d do a layout of story line that was broken down into panels and dialogue. He’d okay it with changes, and I’d write in the copy. Next, I’d sketch a crude layout on sheets of Bristol board that, when completed, would be the final art. Before the lettering was inked in, Will went over and revised, rewrote, and sometimes reconceived as he saw fit, seldom without discussion, sometimes even argument.

“It goes like this a lot with us,” Eisner said in 1988. “Sometimes he always thought I wrote a particular story and I thought he did it. I guess we may never know for sure.”

Whenever possible, Eisner injected humor into

The Spirit

, which humanized his characters and took the edge off some of the stories’ violence. Every so often, as a change of pace, he’d present a story that was almost entirely humorous, and he’d even dabble with parody. This was the case when he published “Li’l Adam,” a send-up of Al Capp’s

Li’l Abner

that in time Eisner would call his “baptism of reality in the comic book world.”