Will Eisner (36 page)

Authors: Michael Schumacher

Ultimately,

The Dreamer

is a fascinating failure, a book that should have been two or three times as long. It could have told a more detailed story about the early history of comics, which would have highlighted Eisner’s important contributions, and it could have addressed the larger issue of anti-Semitism that had forced so many talented artists into the business. The book includes an abundance of interesting stories, but the reader walks away dissatisfied, like someone expecting a feast, only to be served delicious but insubstantial appetizers.

Though he’d been working in comics for nearly fifty years, Eisner found his instructional text

Comics and Sequential Art

a difficult book to organize and write. At the School of Visual Arts, he lectured off the top of his head, using minimal notes. Student questions and interests guided him when he needed to add emphasis to a topic or when he wasn’t being clear enough for his art students to understand. When he set out to write the book, which began as a series of essays in

The Spirit Magazine

, Eisner was on his own.

“I couldn’t find any textbook on the medium that dealt with comics as a discipline, as a true discipline,” he told interviewer Jon B. Cooke. “Most of the comic books at that time—books on comics, rather—dealt with how to draw feet, and how to draw noses, and [took] a very simplistic approach to the drawing aspect of it. Very few of them had attempted to develop a theoretical discussion on the discipline of the medium.”

The lack of available texts, Eisner felt, could be traced to the continuous perception of comics as a type of pop art unworthy of serious scholarly study. “While each of the major integral elements, such as design, drawing, caricature and writing, have separately found academic consideration, this unique combination took a long time to find a place in the literary, art and comparative literature curriculums,” he wrote. “I believe that the reason for slow critical acceptance sat as much on the shoulders of the practitioner as the critic.”

Comics and Sequential Art

was not an instructional book on how to draw feet, noses, or any other part of the human body. In one chapter entitled “Expressive Anatomy” (which he would expand into a book-length study of the same name twenty years later), Eisner wrote and gave examples of how an artist could use the body and gestures as means of expressing emotion; but this was not a book that intended to teach someone how to draw. Instead, Eisner directed

Comics and Sequential Art

at the artist who already knew how to draw and ink but needed guidance on how to apply those skills to creating comics. Chapters included “Imagery,” “Timing,” and “The Frame,” and in writing the book, Eisner was revealing as much about his thoughts and methods as he’d ever allowed outside the classroom. Heavily illustrated with examples from his graphic novels and his work on

The Spirit

, the book showed how to write scripts, do breakdowns and rough pencils, create catchy splash pages, and move on to the finished work. Later editions included a chapter on how to create comics with computers.

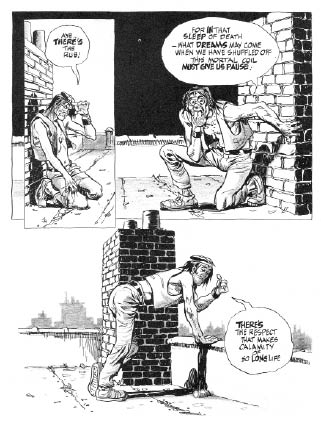

One of the more arresting examples offered in the book was a complete ten-page modern adaptation of the “To Be or Not to Be” soliloquy from

Hamlet

. Eisner and writer/editor Dennis O’Neil had been at a party, engaged in a spirited discussion about the limitations to comics, and Eisner’s piece seemed to rise out of their disagreement.

“I said there were intrinsic limits to what comic books could do,” O’Neil recalled, “and I cited Hamlet’s soliloquy as an example. Six months later,

Will Eisner’s Quarterly

came out with Hamlet’s soliloquy, done by a teenager on a tenement roof.”

Eisner included “Hamlet on a Rooftop” in

Comics and Sequential Art

as an example of how body language and facial expressions could be used to accentuate the written text. Eisner would always insist that

The Spirit

had been influenced by the movies, while his graphic novels were informed by plays he’d seen.

Eisner applied his love of plays to his later graphic work, particularly in his graphic novels. “Hamlet on a Rooftop” became an exercise in applying body language as a means of enhancing text. (Courtesy of Will Eisner Studios, Inc.)

“

The Spirit

was originally done with a cinematic approach because I felt that the language at the time was being impacted by cinema and cinematic ideas,” he told

Time

magazine’s Andrew D. Arnold in 2003. “[But] I was never really satisfied with it. It was interesting and fun to experiment with, but for me live theatre is a reality.”

“Hamlet on a Rooftop” provided concrete evidence of how to bring the theatrical elements of a story to the printed page. The creation of each panel was fully explained with an annotation affording readers a rare glimpse into Eisner’s creative process. More significant, the piece illustrated Eisner’s lifelong insistence on the importance of writing in comics.

“This represents an example of a classic situation—that of author vs. artist,” he wrote. “The artist must decide at the onset what his ‘input’ shall be; to slavishly make visual that which is in the author’s mind or to embark on the raft of the author’s words onto a visual sea of his own charting.”

In analyzing “Hamlet on a Rooftop,” Dennis O’Neil, lauded for his work on the

Batman

and

Green Lantern/Green Arrow

books, saw the piece as representative of the marriage of story and art that made Eisner so effective.

“That was his art—catching the precise moment when the body is most expressive of what’s going on in the mind, and then sort of freezing that and exaggerating a little bit,” O’Neil said. “The art skill is subordinate to the narrative. It’s not showing off and saying, ‘Look what pretty pictures I can draw.’ That’s a happy skill to have, but it’s not comics. With comics, everything should be subordinate to the narrative. He was doing it with Shakespeare, and he was doing it with the stuff he wrote, too.”

The Dreamer

, published by Kitchen Sink Press in 1986, told a story that was half a century old. As Eisner already knew, there were plenty of contemporary dreamers hard at work on graphic novels, and 1986 turned out to be a breakthrough year in the form. In that one year alone, Art Spiegelman, one of the best-known names in the underground comix scene and widely regarded as one of the comics industry’s leading literary practitioners, published

Maus: A Survivor’s Tale

; Frank Miller, who had already garnered critical acclaim for his reworking of

Daredevil

, released his four-part novel,

Batman: The Dark Knight Returns

, a recasting of the character’s legend accredited with saving the character from extinction; and Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons, a British writer/artist team, were publishing the initial installments of their influential twelve-part

Watchmen

series. In

Faster Than a Speeding Bullet: The Rise of the Graphic Novel

, comics scholar Stephen Weiner labeled 1986 “a turning point” in the comics industry: “From then on,” he wrote, “cartoonists aimed higher and hoped more than ever that their books would break—or at least peek—out beyond the traditional comic book readership, and focused more on stories holding appeal to readers who didn’t care for traditional comic books.”

Although all four were young enough to have been Eisner’s children, and had learned aspects of their craft by looking at his oeuvre, they were all fiercely individualistic and dedicated to their own work, with colorful histories in comics prior to the publication of these seminal graphic novels.

Spiegelman, a product of the undergrounds, shared Eisner’s passion for the literary possibilities of comics as well as his distaste for superheroics. The son of Polish Jewish concentration camp survivors, Spiegelman grew up in New York, where he attended Manhattan’s High School of Art and Design. He connected with the publishers of underground comix in the late sixties, and his work appeared in a variety of publications, including

Bijou Funnies

,

Bizarre Sex

,

Comix Book

, and

Snarf

. His more commercial work included a twenty-year stint with Topps, the chewing gum company best known for its sports cards. Spiegelman, who cited

Mad

magazine’s Harvey Kurtzman as one of his major influences, created the Garbage Pail Kids and Wacky Packages for the company. In 1980, he and his wife, Françoise Mouly, founded

Raw

, an influential annual book-length anthology of innovative sequential art, which included early installments of

Maus

.

Maus

was the most complex work of sequential art ever created. It is the story of one family’s survival of the Holocaust, but it is also a memoir of how a young artist came to terms with his complicated, prickly relationship with his father and of the relationship between an artist and his art. Spiegelman was unsparing in his portrayal of the book’s characters, including himself, leaving to readers the tasks of sorting through the details and answering the book’s crucial questions about what is right and good in the face of annihilation and, perhaps more complicated, what is right and good once that threat is gone.

By the time

Maus: A Survivor’s Tale

was published by Pantheon Books, Spiegelman had been living with the project for what seemed like a lifetime, literally and figuratively.

When I began to work on

Maus

, there wasn’t such a thing as a graphic novel, but there also wasn’t a body of literature about the Holocaust that would take several lifetimes to read. So it was really just a matter of time to figure out “What happened to my parents, and how did I get born?” When I started the book, my father was very much alive, and by the time I was halfway through with it, he was dead.

The Holocaust, of course, was a monumentally tragic story, and any telling of it could not be diminished by the wrong kind of writing or art. On a personal level, Spiegelman had tremendous loss as deep background to his writing: his older brother and only sibling, Richieu, had been a victim of the Holocaust, poisoned by his caretaker-aunt rather than be deported from the Zawiercie ghetto and sent to almost certain death at the camps; and his mother, Anja, had committed suicide in 1968. Spiegelman’s decision to use anthropomorphic animals to tell his story—the Jews were mice; Germans, cats; Polish, pigs; and Americans, dogs—was bold and risky and almost certainly would have backfired in a writer/artist of lesser talent. Even so, it took a while for this creative process to ferment. The first volume of

Maus

, eventually subtitled

My Father Bleeds History

, concentrates mainly on Spiegelman’s relationship with his father and his process of self-discovery and is populated almost exclusively by Jews as mice; a second volume,

Maus II: And Here My Troubles Began

, published five years later in 1991, flashed back to the horrors of the concentration camps and required the delicate working in of the other zoomorphic ethnic groups and nationalities.

Frank Miller, who would eventually become involved in the movie business, including as director of a film adaptation based on Eisner’s

Spirit

, was heavily influenced by film and by the violent urban setting he saw after moving from Vermont to New York. Although, like Eisner, he was more interested in telling adult stories than in depicting superheroes in tights, he was also astute enough to recognize that the superhero presented him with his entrée into the comics world. When he had the opportunity to work on

Daredevil

, a slowly sinking Marvel title about a blind crime fighter, he added hard-edged elements of film noir that would later become his trademark in his

Sin City

graphic novels. His work was daring, uncompromising, flashy, brutally authentic, moody, and violent—and readers responded enthusiastically, boosting the title’s circulation to the point where Marvel started publishing it on a monthly rather than bimonthly basis. The success of his

Daredevil

series led to other assignments, most notably a short run on the

Wolverine

spin-off of Marvel’s immensely popular

X-Men

series, and the

Ronin

miniseries, which he created. His involvement with

Batman

began with a one-shot appearance as the illustrator in a 1980 Dennis O’Neil–written Christmas story.

Batman

had gone through a number of permutations since Bob Kane created him, including a television run as a parody, and Miller saw potential for further development of the character, not as the heroic “Caped Crusader slavishly devoted to the law,” but as the “Dark Knight,” a wealthy vigilante working almost as far outside the law as the criminals he was facing. Miller’s Batman was in his late fifties, retired from crime fighting, haunted by his past, and angered enough by the present violent society to leave retirement. There were no

POW

s and

BAM

s in Miller’s version; Batman was as apt to throw a bad guy off a building as offer him a chance to surrender. In

The Dark Knight Returns

, Miller ushered in a Batman for adults, a female Robin, a seriously unfunny Joker, a Gotham City that was darker than ever, and action that moved at a breakneck pace from frame to frame.