Will Eisner (40 page)

Authors: Michael Schumacher

Pincus Pleatnik, Eisner explained in an introductory note to the story, was a composite of the people he’d seen on the street during his youth. Like most other New Yorkers, he passed by without paying them a shred of attention.

“I grew up accepting this as a normal phenomenon of metropolitan life,” he wrote. “Only years later did I realize how pervasive was this brutal reality and how people often accept, even welcome, invisibility as a way to deal with urban danger.”

If “Sanctum” dealt with the worst possible results of

predictable

invisibility, “The Power” showed how even great promise might slip into such a state. There’s no question that Morris, the main character in this story, is special. He discovers early in his life that he has the power to heal humans and animals, and rather than manipulate that power for fame and wealth, he decides to use it for the greater good. He wanders aimlessly from job to job, hoping to make a difference, only to slip into obscurity. When a scam artist from a circus finds him, she announces that he is the father of her young boy, who is hobbled by a birth defect and needs someone to heal him so he can walk. Morris hopes to be a good father, while the boy and woman are interested in him only for his powers. But Morris is unable to heal the child, and the woman and child abandon him in his final obliteration.

The third story, “Mortal Combat,” is an account of a spinster librarian named Hilda, who has no life other than as caretaker to her aging, demanding mother. When she meets and falls in love with Herman, a colleague at the library, her mother, who doesn’t want to share her daughter with anyone, threatens her relationship. Their love is all that gives Hilda’s and Herman’s lives any definition, and their life together is brought to a horrible conclusion when Hilda’s mother, now bedridden, accidentally sets the apartment on fire, killing the two women and leaving Herman permanently disabled.

“In relating the story of Herman, who became the unwilling prize in a clash of wills, I hoped to evoke the helplessness of a person caught in an intersection of the traffic of life,” Eisner wrote of the story. “Herman’s dilemma is one of the dangers of group living.”

Coming on the heels of such a lengthy, ambitious work as

To the Heart of the Storm

,

Invisible People

seemed like a minor work retracing steps already taken elsewhere. Eisner worried about this in a letter to Dave Schreiner. “I expect I’ll be criticized by the younger critics for repeating myself,” he predicted. “But I’ve wanted to deliver myself of these themes for some time—maybe on the next book I’ll try some new arena.” Schreiner, aware of the inspiration for the stories, was sympathetic. “You have to let these things out or they keep on bothering you,” he advised. “You are an artist and writer and, while you can’t do these things in a vacuum, I think it would be very dangerous to let a critic guide you. You wouldn’t be true to yourself then.”

Eisner labored over the three stories, from the naming of his characters to the titles of the stories themselves. He knew what he wanted to accomplish, but he seemed lost as to how to get there. “Sanctum” went through numerous drafts as Eisner struggled to fit the message of the Carolyn Lamboly story within the framework of his tale about Pincus Pleatnik. He drew several different rough pencil covers for the proposed single-story Pincus book, using such titles as “The Hider,” “Safety,” “Sinkhole in the City,” “Sinkhole,” and “Invisible,” before eventually settling on “Sanctum.” But he grew so frustrated that he wrote Schreiner and begged for help. “Still flailing at the title,” he told his editor, undoubtedly remembering his issues with Schreiner over the title for

To the Heart of the Storm

. “For heaven’s sake pick one and help me go on with this monster in peace!!!”

The

Invisible People

trilogy was marketed with a unified cover design and logo, with Eisner’s name prominently displayed on each of the three covers, each book distinguished by its different art and title. However, readers weren’t as compelled to buy all three books as they might have been if it had been a continuing story, and sales lagged behind expectations. The sales figures were similarly disappointing when the stories were gathered into a single volume. It could be that Eisner had gone to the proverbial well one time too often, that readers weren’t drawn to the book as intensely as to some of his earlier efforts, as Eisner had originally feared, or it could have been that a downturn in the market affected sales. Whatever the reason,

Invisible People

, for all Eisner’s passion and the work that went into it, was now officially a minor work in the Eisner line.

When Eisner celebrated his eightieth birthday on March 6, 1997, Ann marked the occasion by throwing a surprise party at the International Museum of Comic Art, a huge affair attended by friends, family, and business acquaintances. Eisner was in remarkably good physical condition for someone his age—or even two decades younger—and he was producing more than ever. Nearly twenty years had passed since the publication of

A Contract with God

. In the years since the book’s publication, he had produced more graphic novels than anyone in the business. He had reached the age where he was the subject of career retrospectives, he’d received more awards than he could keep track of—including the Milton Caniff Lifetime Achievement Award in 1995—and the University of Massachusetts had hosted an important conference on the graphic novel.

To those who knew them, Will and Ann Eisner were a model couple, as happy together late in life as they were when they initially met. (Courtesy of Denis Kitchen)

His international fame only added to his sense of accomplishment. His books had been translated into more than a dozen languages and had appeared in Europe, South America, and Asia, published by prestigious houses willing to give him the kind of exposure and circulation that American comics artists would have envied in their own country. He was invited to global comics conventions, where he was greeted as an icon. In 1996, he designed a special mural from his “Gerhard Shnobble” story for the side of a building in Copenhagen, and

The Spirit

had even appeared on the Berlin Wall before it was brought down.

Still, the acclaim wasn’t enough. He was approaching his career goals, but he still felt confined in a comics ghetto. His awards were industry awards; his books were still limited to the comics section of bookstores, next to the superhero books and away from general interest or literary fiction shelves. Art Spiegelman had won a Pulitzer Prize for

Maus

, and newspapers were now devoting at least token space to reviewing higher-profile graphic novels, and while these were important steps forward, Eisner was growing impatient.

The key, he felt, was survival—waiting for the world to finally put the final pieces in place and his living long enough to see it happen.

New, unexpected projects popped up out of nowhere. One, originating from a Florida public television channel in the mid-1990s, combined Eisner’s love of adapting classic literature to sequential art with his continuing interest in using comics as a teaching tool. The Florida television station had come up with the idea of producing a series of what could best be described as electronic comic books, in which there would be very little animation other than dialogue balloons that would be read by young viewers. Eisner’s job was to supply the artwork, which was similar to storyboards used in movies.

“I developed what I called a reading experience on television,” he explained. “I took the classics and reduced them to a little half-hour show in which there was no animation in the art, but the balloons were animated, so the language would pop in as the characters spoke it, and that would force the reader to read it. Well, it never went anywhere. They couldn’t get enough funding to pursue it, and I was left with a bunch of stories.”

The stories, in the form of pencil dummies, were filed away but not forgotten. Eisner, who never threw away a scrap that might eventually be recycled or worked into something, talked about the ill-fated television project with his agents and publishers overseas, and to his surprise, he learned that libraries were interested in stocking these comics as children’s books. By then, Eisner had moved on to other graphic novel projects, but he found a way to satisfy the demand for these children’s books without compromising his work on adult material. He worked on the adaptations after he’d completed one of his graphic novels, using them as sort of a cool-down exercise. “After I finish a heavy book,” he explained, “I find that doing something very light is a great antidote.”

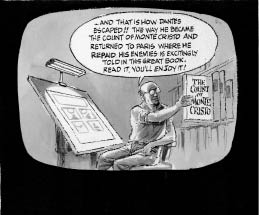

Self-portrait from the unpublished

Count of Monte Cristo

. Eisner hoped to use comics to adapt the classics for young educational television viewers, but a lack of funding killed the project. (© Will Eisner Studios, Inc., courtesy of Denis Kitchen)

Unpublished panel from

The Count of Monte Cristo

. (© Will Eisner Studios, Inc., courtesy of Denis Kitchen)

Eisner enjoyed the break. Aside from adapting some of the stories he’d enjoyed as a boy, he was able to put his own spin on some of the classics, such as in

The Last Knight

, his adaptation of

Don Quixote

, where he included a scene in which Don Quixote meets Miguel de Cervantes, his creator. Publication of the books was spaced over a period of years, in Europe and Brazil and, eventually, the United States. Four titles—

Moby Dick

(1998),

The Princess and the Frog

(1999),

The Last Knight

(2000), and

Sundiata: A Legend of Africa

(2003)—were issued by Nantier, Beall, Minoustchine Publishing in hardcover and paperback editions, including limited, signed, and numbered editions.

Another project, requiring far less attention, involved Eisner’s return to his most famous character in a series of new Spirit adventures. Denis Kitchen had always favored such a project, but Eisner, fearing that it would turn

The Spirit

into a “mausoleum” piece, resisted creating, or allowing others to create, new stories. Kitchen persisted, arguing that

Spirit

fans would want to know what had happened to the Spirit after all these years, and when they finally came to an agreement, Eisner did the worst possible thing: he turned in an insipid story entitled “The Spirit: The Last Hero,” a piece guaranteed to disappoint the character’s most loyal readers. Kitchen had no choice but to reject it.

Kitchen wasn’t finished, though. The comic book industry was staggering through an economic downturn in the mid-1990s, and Kitchen Sink Press, never a corporate giant like DC or Marvel, was in trouble. Kitchen and his staff tried to keep the company afloat through innovative merchandising and reprints of classic comics, but with the exception of their tie-in with the immensely popular film

The Crow

, sales figures lagged far behind expectations. New

Spirit

stories, Kitchen reasoned, could only help prop up his business. If Eisner, now totally focused on his graphic novels, wasn’t up to producing new stories, maybe others could. It would be a way of showcasing the talents of the top comic creators of the day while simultaneously paying tribute to the artist who had influenced them.