Will Eisner (38 page)

Authors: Michael Schumacher

Eisner supported efforts to help comic book creators with their rights, but as a businessman he also felt a conflict. After all, he’d run a comic book studio not all that different from the others of the time. Granted, he’d created almost all the characters originating from the Eisner & Iger shop, but it was his name, or a generic nom de plume, that was affixed to the comics, and his shop maintained ownership and the copyrights on the art. He’d negotiated what he thought was a fair deal with Busy Arnold for ownership of the Spirit and other characters that he’d created for Quality Comics. At the same time, he resented losing ownership of the characters and art he’d produced while he was with

P

*

S

magazine, and he made certain that would never happen again. As he saw it, comics were business, and there would inevitably be a give-and-take between the artist and the company buying his or her work. The individual was ultimately responsible for negotiating his or her rights.

Still, it rankled him when he heard about other comics artists—especially the pioneers who had paved the way for the big companies—having to struggle to gain credit for their creations or fight to have their artwork returned. When Jack Kirby became involved in a protracted battle with Marvel to get his original art returned, Eisner was compelled to act on his old friend’s behalf. In an “Open Letter to Marvel Comics,” published in the

Comics Journal

’s August 1986 issue, Eisner chastised the company for keeping what he considered to be Kirby’s property.

“This matter has gone beyond whatever legal merits there may or may not be to your position,” Eisner wrote. “By your public intransigence you are doing severe damage to an American cultural community that is now emerging from the dark years of trash and into an era of literary responsibility.”

Eisner’s tone was firm and direct, as close to open anger as he would permit himself in print. The Kirby story had been perplexing and very public. Kirby had produced thousands of pages of art for Marvel during the 1960s, but when he asked for its return, Marvel offered him a mere eighty-eight pages—and only under the condition that he sign a document in which he all but disclaimed any connection to the characters he had produced for the company. Copyright and ownership weren’t negotiable. Kirby refused to sign the document, but he also balked at the suggestion that he sue the company. Like Siegel and Shuster, he was getting old and was in poor health, and he wasn’t certain he’d live to see litigation worked out in court. The

Comics Journal

took up his cause, closely following and reporting the case, which was gaining momentum by the time Eisner wrote his letter in 1987. Marvel was under no legal obligation to return the art, and like DC before them, they feared that capitulating to Kirby’s request might set a precedent the company didn’t want to deal with in the future.

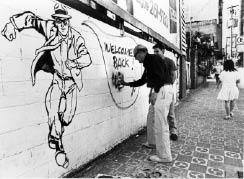

Eisner enjoyed great international appeal, and it was never more evident than when someone painted

The Spirit

on the Berlin Wall. (Courtesy of Denis Kitchen)

But this was precisely Eisner’s point.

“A whole new generation of creative people [is] watching your conduct,” Eisner warned Marvel at the closing of his letter. “Don’t fail them!”

Marvel eventually returned more than two thousand pages of Kirby’s art, though the company retained the copyrights on the work and ownership of the characters Kirby had created or co-created for the company. For Kirby, it was a bittersweet victory, but about the best he could have expected.

Over the course of his career, Will Eisner received numerous inquiries from Hollywood producers about the possibilities of optioning the rights to

The Spirit

for a motion picture or television adaptation, but he could never work out an arrangement that accommodated the demands of the entertainment industry while maintaining the integrity of the character. Those making the inquiries were always looking to update the character in a modern urban setting, convert him into an action hero, dress him in tights or a cape—anything but that hopelessly dated fedora and suit—or give him superpowers. Eisner rejected such offers without hesitation.

If

a theatrical motion picture or made-for-television movie were to be made out of

The Spirit

, it would have to remain faithful to his vision. What gave the Spirit his appeal was the fact that he was good-looking and strong, yet vulnerable, capable of getting into life-threatening binds or even being outwitted by a beautiful woman; he had to use his wits, rather than gadgets, to save the day. Eisner favored James Garner, who played this type of character in the 1960s television western

Maverick

, but they never hooked up while Garner was young enough to play the Spirit.

Signing his art in São Paulo, Brazil, in 1987. (Courtesy of Denis Kitchen)

Some of those interested in

The Spirit

were worthy of consideration.

In the early sixties, Anthony Perkins, still flush from his breakthrough role in Alfred Hitchcock’s

Psycho

, contacted Eisner with the hope of optioning

The Spirit

for the movies. There was a fair amount of money involved, but after talking to Perkins, Eisner had to decline.

“I asked him what his idea was for a movie,” Eisner recalled, “and he said, ‘Well, I see the Spirit as a sort of a mystic, as a magician of some kind.’ That’s clearly not what I had in mind. The deal never went anywhere, of course, because I wasn’t interested in a Spirit movie where he was a supernatural figure, even if it would be a successful movie. It’s not that I dislike making money, but I am very loyal to the ideas I hold about my characters.”

William Friedkin, director of

The French Connection

and

The Exorcist

, succeeded in optioning the motion picture rights to

The Spirit

, but bringing the character to the big screen proved to be elusive. Harlan Ellison, the award-winning writer and screenwriter whose work touched upon every type of fiction imaginable, worked on a screenplay, as did Jules Feiffer, who had successfully adapted

Popeye

for Robert Altman’s film. Even Eisner gave it a shot. None of the scripts met Friedkin’s approval, and the project died in development.

There had also been an attempt to launch an animated version of

The Spirit

in the early 1980s, and when Eisner agreed to option the film rights to the character, he was confident that he had a good team working on the feature. Gary Kurtz, producer of

American Graffiti

,

Star Wars

, and

The Dark Crystal

, was on board in a similar capacity, while relative newcomers Jerry Rees and Brad Bird were hired to write the screenplay. Bird, who would eventually make his name as director of such films as

The Iron Giant

,

The Incredibles

, and

Ratatouille

, had created a rough pencil trailer of a possible

Spirit

project with Rees and several Cal Arts students, and Eisner was impressed when he was shown the work.

“I will be interested to see it,” Eisner told an assembly of reporters covering the Tenth Annual International Salon of Comic Books in Angoulême, France, where he was the 1984 convention’s guest of honor. Although he’d tried to distance himself from comparisons of comics and the movies after he began producing graphic novels, Eisner still saw a connection between the two media. “In the beginning were the comics, then the movies,” he stated. “Cinema came from comics; I regard film as an extension of comics.”

Unfortunately for Eisner and the others, the timing for finding backing for such a project was bad, and Eisner’s original hopes of aiming the

Spirit

newspaper feature at adults worked against him in the movie project. These were times before animated films were geared for adults, and Walt Disney Studios, the standard-bearer for movies marketed to children, was financially troubled and in a state of flux. Development on the movie was shelved, and the option eventually expired.

When a made-for-television movie was finally produced in 1986 and broadcast a year later, it was an unqualified disaster, not for a lack of effort on the part of those making the film, but for reasons no one could have predicted when the project was in the planning stages. The deal with ABC and Warner Brothers Television called for a ninety-minute movie, which would be used as a pilot for a television series—which, in theory, sounded like a good idea. After the Spirit and his origins were introduced to television viewers in the pilot, the ensuing programs could follow Eisner’s old episodic structure. Rather than try to set the movie in the past, which the budget wouldn’t permit, or update the character to the present day, which Eisner wouldn’t allow, the director and screenwriter placed the Spirit in a stylized limbo, a place that was neither past nor present, with buildings and cars that could have existed at any time. Ebony, for obvious reasons, was out, replaced by a new sidekick named Eubie. The script was written by Steven E. de Souza, whose 1982 film,

48 Hrs.

, had been a major screen success.

Unfortunately, for reasons beyond the understanding of de Souza and others working on the film, ABC insisted that the role of the Spirit be given to Sam J. Jones, a handsome young actor who looked like Denny Colt but couldn’t act the part. Will Eisner’s character was a man of action, which Jones could play convincingly, but he was also highly nuanced—thoughtful, funny, vulnerable, not unlike George Lucas and Steven Spielberg’s Indiana Jones—and for all his efforts, Jones couldn’t master these qualities. Instead, he came across as an action hero indistinguishable from those viewers had seen before.

Even so,

The Spirit

might have caught on as a television series, and Jones might have had the chance to grow into his part, if big business hadn’t entered into the picture. While

The Spirit

was in the midst of production, ABC changed hands, and the new powers-that-be didn’t share the previous management’s enthusiasm for the project. Rather than air the movie in an opportune, prime-time slot during the regular programming season, ABC broadcast it in the middle of the summer, on July 31, 1987, in the heart of the rerun season, when viewers traditionally stayed away from their television sets. The ratings were awful, and the movie was never rebroadcast.

The Spirit

television series never materialized.

After seeing the movie, Eisner, reminded of why he had resisted offers for a

Spirit

movie adaptation for all those years, was relieved by the cancellation. “It made my toes curl,” he said.

Not that he was surprised by the project’s failure. In a letter to Denis Kitchen written a year prior to the movie’s airing, Eisner lamented the state of the project. He’d screened a tape of the film and wasn’t fond of what he saw.

“They have about 2 million dollars invested in this ‘dud,’” he told Kitchen, “but I can’t weep for them because they never consulted me—or let me near the project. I’m only sad that the hopes we had of widening our audience has gone up in smoke.”

By now, Eisner was accustomed to receiving his share of industry accolades and to seeing his name included on the short list of the influential founding fathers of the comic book, but he was unprepared for the call he received from Dave Olbrich, an administrator of the annual Kirby Awards handed out for excellence in the comics industry. The awards, Olbrich informed Eisner, were being discontinued. Would Eisner consent to having his name attached to similar awards?

Eisner had reason to pause before answering. The Kirby Awards, named after comics great Jack Kirby, his friend and former protégé, were being discontinued because of a dispute between Olbrich and Gary Groth, Olbrich’s former boss at the

Comics Journal

. Olbrich’s split with Groth had been nasty. There had been a power struggle over the Kirby Awards, to such an extent that Kirby himself had asked that his name be removed from the awards. Fantagraphics was starting up a new set of awards named after Harvey Kurtzman. Aside from his own falling-out with Groth, Eisner had other issues to consider. Kurtzman was still one of his close friends, so other awards might be seen not only as competing, but even as an affront to another great artist.