Will Eisner (32 page)

Authors: Michael Schumacher

Eisner was one of the few people in comics who had actually worked in trade publishing. At American Visuals, Eisner had produced hardcover books for the educational market on several topics, including one on space and rocketry. He had played a variety of roles, as coauthor, designer, art director, doing what is now called packaging. Eisner understood book marketing, binding, illustration, trim size and shelving by category. No one else in comics at that time had the same direct experience of the book market and editorial work that Eisner did. Someone else, editors and designers at the trade houses who licensed the publication from Marvel, packaged Stan Lee’s books. Underground anthologies barely penetrated the bookstore market, finding shelf space in alternative book stores and comic shops. Eisner’s knowledge formed part of the background for the creation of

A Contract with God.

Using this knowledge of publishing, Eisner created a book that didn’t look like a comic book. It was the size of a trade paperback, had lettering on its spine, boasted a cover design that didn’t scream “children’s book” to bookstore owners and librarians, and provided an interior that eschewed the panel-by-panel artistry typical of comic books. Eisner had always been a voracious reader, and besides his knowledge of what constituted serious literature, he knew what a book should

look

like. “When Eisner turned to creating a novel in comics,” Couch concluded, “he had both a publishing professional’s understanding and inveterate reader’s physical, tactile grasp of what a novel should be.”

Newspapers and general interest magazines didn’t review comic books of any type—not in 1978—so Eisner had his hands full trying to reach potential readers. The book received extensive advertising in

The Spirit Magazine

, which was to be expected, and comics journals and fanzines noted its publication. (In a lengthy review in the

Comics Journal

, reprinted as an introduction to later printings of

A Contract with God

, comics writer and editor Dennis O’Neil, evoking the literature of Bernard Malamud, Philip Roth, and Isaac Bashevis Singer, called

A Contract with God

“a near masterpiece.”) Beyond that, publicity for the book was all word of mouth.

Bookstores had no idea how to display or stock

A Contract with God

, as Eisner determined shortly after its publication, when he took a call from Norman Goldfine, Baronet’s publisher, who informed him that the Fifth Avenue Brentano’s in Manhattan was stocking his book. Eisner was elated. Having a store like Brentano’s carry

A Contract with God

seemed to underscore his claim that adults would be receptive to serious graphic novels. To avoid looking like an overeager author checking in on his book, Eisner waited two weeks before venturing to the store. After looking for the book and not finding it anywhere, he approached the store manager, identified himself as the author of

A Contract with God

, and asked how it was selling. The manager replied that the book had been prominently displayed for a couple of weeks, had sold well, but had to be relocated when the new James Michener novel arrived in the store.

“What did you do with mine?” Eisner wanted to know.

“Well,” the store manager said, “I brought it inside and I put it in with religious books since it’s about God, and this little lady came up to me and said, ‘What’s that book doing there? That’s a cartoon book. It shouldn’t be in with religious books.’ So I took it out and I put it into the humor section where they have people like Stan Lee and so forth. And someone came to me and said, ‘Hey, this isn’t a funny book; there’s nothing funny in this book. Why do you have it here?’ I took it out of there, and I didn’t know where to put it.”

Eisner had anticipated this sort of problem. Bookstores, like publishers, liked the convenience and comfort of labels. Genre fiction was ideal, with such categories as science fiction and fantasy, romance, westerns, humor, and horror making books easy to classify; everything else could be stocked under the category of general fiction.

A Contract with God

defied categorization. It wasn’t a collection of comic strips, which usually found a place near the back of the store, but it wasn’t prose fiction, either.

“Where do you have it now?” Eisner asked the store manager.

“In a cardboard box in the cellar,” the manager responded. “I don’t know where to put the damn thing.”

One of Will Eisner’s favorite pieces of his own work was a single-panel drawing, a self-portrait with no caption or dialogue balloon. Eisner portrays himself, leaning casually against a crude, makeshift newsstand stocked with copies of his graphic novels. The stand is set up in the middle of nowhere. The land around him is hilly but barren. Three birds fly in a cloudless sky.

Eisner looks off into the distance.

On the horizon, far away, a cloud of dust is being raised by a throng of people heading in his direction.

Eisner could wait.

chapter twelve

O U T E R S P A C E , T H E C I T Y —

N O L I M I T S

Think of me as a one-man band, walking down the street with a sign saying “Sequential Art,” every once in a while looking around and there’s somebody following me, but the line isn’t too big at the moment.

P

leased with the results of

A Contract with God

, Eisner started another graphic novel, this one to be written and published in a radically different way. Beginning with the third Kitchen Sink issue of

The Spirit Magazine

in 1978, Eisner serialized

Life on Another Planet

(later published in book form as

Signal from Space

), which presented more drama and less humor than had been the trademark of

The Spirit

, with a larger cast of characters plopped down in a world that allowed Eisner the opportunity to comment on the human condition more than ever before. A year prior to the publication of the first installment of Eisner’s story,

Star Wars

, George Lucas’s space opera, had shattered box office records and jacked interest in science fiction and fantasy to a new level. But

Signal from Space

was light-years from

Star Wars

, more James Bond than Luke Skywalker, complete with a cold war, international espionage, murder and mayhem, exotic settings, crooked politicians and corporate officials, a Nixon-like ex-president named Dexter Milgate, an Idi Amin–like African dictator named Sidi Ami, treacherous female villains, and conflicted heroes. The feature, running in sixteen-page installments, appeared in eight consecutive issues of

The Spirit Magazine

, beginning in October 1978 and concluding in December 1980.

In this case, creating the story and art was the equivalent of working without a safety net. Eisner had begun the project with the idea of building a story about the repercussions roiling around the discovery of another form of life on a planet a mere ten years’ travel distance from Earth. But whereas with

A Contract with God

he’d carefully plotted out the stories before penciling them, here Eisner was virtually improvising, with no real idea where he was taking this graphic novel. The first installment/chapter opened with two scientists receiving a transmission from somewhere out in space, and from that point on Eisner just let his imagination take him wherever it chose.

“I’m gonna let it happen, just do it and let it happen,” he told the

Comics Journal

shortly after the first installment’s appearance in

The Spirit Magazine #19

. The uncertainty, Einser said, added to the excitement of creating a new story. “I don’t know what the second chapter is going to be yet,” he admitted, “but I’ll do that very shortly.”

Eisner’s plans for presenting the continuing installments differed greatly from anything he’d done before. Rather than publish in the traditional comic book way, he and Denis Kitchen decided to experiment with a pull-out section that readers could remove from the magazine and cut and fold, creating a booklet in the process. The idea sounded good in theory, but Kitchen received complaints from distraught collectors who didn’t want to tear apart their magazines.

“There has been a universal ‘nay’ vote from readers in response to the format of ‘Life on Another Planet,’” Kitchen wrote Eisner. “Fans seem to like the story but resent having to clip their copy or reading in a helter-skelter manner.”

Eisner was disappointed by the news, but he agreed to drop the insert idea. “In view of information relating to the consistently ‘NAY’ vote on the format for LIFE ON ANOTHER PLANET, I have to accept the reality that the insert idea just won’t work,” he wrote in response to Kitchen’s letter. “Too bad … I guess I misjudged the attractiveness and practicality of this ‘gimmick.’”

Kitchen later admitted to having reservations about the feasibility of the project. “I knew instinctively that my generation had this ‘collector’s gene,’” he said. “They didn’t want to cut things up. They didn’t want to turn the magazine sideways. But we had to test it to prove it. If it worked and we got a lot of people writing and saying, ‘Hey, I really dig this,’ we’d do more, and if they complained, we’d rethink it. We couldn’t afford a real market survey.”

Signal from Space

posed problems that Eisner hadn’t encountered with

A Contract with God

. He had mastered the short form of comics writing dating back to his earliest years in the business, and the longer pieces in

A Contract with God

, although more challenging, had involved his fleshing out the elliptical elements of comics writing. Pacing and exposition weren’t major considerations.

Signal from Space

was not only significantly longer and more complex than anything he had ever attempted; since it was being published in installments, Eisner had to find subtle ways to keep readers connected to his graphic novel’s characters and subplots from issue to issue of the magazine. Prose writers faced similar challenges when writing by installment, but they weren’t trying to align image and text the way comics writers were, and the difference between a phrase (or even a paragraph) of prose and a comics panel was monumental. For the sake of clarity and pacing, Eisner generally preferred to limit a scene to a single page, but that didn’t give him much wriggle room in each installment’s sixteen pages, especially when one of them was a splash page.

Signal from Space

was full of the usual Eisner trademarks: innovative camera angles, lighting, and movement, with more dialogue than usual.

Fortunately for Eisner, he had ample input from a publisher and, for the first time in his career, an editor. The former, Denis Kitchen, was vastly experienced in comics; the latter, Dave Schreiner, was more heavily involved with the written word.

As a publisher, Kitchen was aware of the market, and he knew, as a fan and collector, what appealed to him personally. Kitchen Sink Press was a small operation, with a small staff and very limited funding, and as pleased as he was to be publishing Will Eisner, Kitchen was by no means in the position to absorb many losses. The graphic novel was unexplored territory, and Eisner and Kitchen were mapping out its terrain as they went along. Schreiner, a Wisconsin freelance editor and old friend of Kitchen’s, possessed extensive knowledge in contemporary literature and was brought on board to act as a buffer between publisher and artist.

Kitchen and Schreiner went back a long way, to their days at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, when both were contributing to the student newspaper, Kitchen as a cartoonist, Schreiner as the paper’s sports editor. The two became close friends and, eventually, co-founders of the

Bugle-American

alternative newspaper. “You get to know a person pretty well when you work with him all night, week after week, pasting bits of paper on layout sheets,” Schreiner wrote of Kitchen in

Kitchen Sink Press: The First 25 Years

, his history of Kitchen’s publishing enterprise.

The demise of the

Bugle-American

hit Schreiner hard. He had been the driving force behind the paper, and he took the loss personally. For a longer time than he’d ever care to admit, he drifted aimlessly, working a string of menial jobs and drinking so heavily that he almost lost his life. The rehabilitation was slow and difficult, but once he was sober and rebuilding his life, he reconnected with Kitchen and began working at Kitchen Sink Press as an editor.

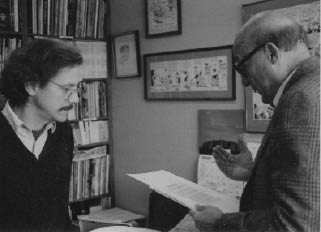

Artist and editor: Dave Schreiner worked with Eisner as an editor and advisor on all but his first and last books. Eisner looked for an editor who could be brutally honest with him, and Schreiner fit the bill. (Photo by Doreen Riley, courtesy of Lesleigh Luttrell)

Taking the job with Kitchen Sink, he wrote in his history of the company, was “equal parts rewarding, frustrating, exciting, and boring.” His editing of Eisner and others, he continued, was the source of his greatest satisfaction.

It gave me the opportunity to do some real editing; that is, trying to facilitate their work. Acting as a sounding board, working out problems, debating story points—that was all stimulating. Comics still offers that type of atmosphere to editors. In the book publishing world, it’s all marketing; in comics, editors can still actually work with creators. And, if these editors aren’t too stupid or egotistical, they can perhaps make that work better.

Kitchen and Schreiner treated Eisner’s work very cautiously in the beginning. Eisner’s credentials had been established before either of them was born. They felt fortunate just to be working with him, and they were reluctant to be too forceful in stating their opinions about his new work. Eisner, however, felt differently. He wanted direction, not patronizing from fanboys or sycophants.

“When I was reprinting

The Spirit

, I remained very respectful,” Kitchen noted of his early working relationship with Eisner. “There was nothing to say about the stuff from that long ago, other than ‘Wow! This is really great!’ But right after

A Contract with God

, when I started publishing his graphic novels, he requested feedback. Will had a conversation with me on the phone one day. He said, ‘I expect honest editorial feedback. You’re not a good publisher if you aren’t completely honest with me. Look at the work objectively. Tell me if you think I’m wrong. I demand objective feedback.’ I remember turning to Dave after that conversation and saying, ‘Will doesn’t want us to pull our punches,’ and Dave said, ‘Good.’ It went better than ever at that point, because it was like the gloves were off. Dave was very good at what he did, and Will recognized that early on. Dave was an editor’s editor. It wasn’t about his own ego; it was about making the work better.”

“He often referred to the publishing operation as being no more than a conduit between the creator and the reader, and the work published during his tenure reflects that,” said graphic novelist Jim Vance (

Kings in Disguise

), who succeeded Schreiner as editor in chief at Kitchen Sink Press after the company moved to Massachusetts and Schreiner decided to stay in Wisconsin. “Dave was soft-spoken and had a wit so dry you could cut yourself on it. He was utterly blunt when it came to discussing your work. If he thought you were painting yourself into a corner, he’d let you know in no uncertain terms, but there was never the sense that you were being bullied or insulted. On the job, he was a no-nonsense guy who had to deal with his share of flakes and prima donnas, and he was apparently unflappable no matter what was presented to him.”

Not that Eisner went along with all—or even a majority—of Schreiner’s or Kitchen’s suggestions. According to Kitchen, Eisner would listen to his (or more often Schreiner’s) suggestions, consider them, and make a decision. Much of this work was done through the mail, with Schreiner handling the bulk of the correspondence from the Kitchen Sink end. The exchanges were almost always cordial, but they could get a little chippy if Eisner felt that Kitchen or Schreiner didn’t understand his position. Kitchen recalled one particular series of exchanges that occurred when he and Schreiner were pushing Eisner to expand an autobiographical vignette that eventually became

The Dreamer

, Eisner’s third graphic novel. Eisner was satisfied with it at story length, similar to the pieces he’d published in

The Spirit Magazine

and, later,

Will Eisner’s Quarterly

, but Kitchen and Schreiner, captivated by Eisner’s anecdotes from his earliest experiences in comics and believing that readers would respond in a similar way, asked for more. Eisner wasn’t eager to comply. “He did it with great resistance,” Kitchen allowed. “We got that one expanded from about sixteen pages to about fifty. We would have wanted it to be one hundred–plus pages, but he just wouldn’t do it.”

Eisner wanted his work to be judged as literature, and Schreiner held him to literary standards. Schreiner read Eisner’s work as he would a novel, and he expected Eisner to honor the rules of the novel, from characterization to plotting, from point of view to pacing. The key to dealing with Eisner was to be straightforward but diplomatic. Eisner had a favorite expression—“Don’t tell me how to do it, just tell me what’s wrong”—and Schreiner would work off that.

Denis Kitchen would often overhear the telephone conversations between Schreiner and Eisner, and he was impressed with Schreiner’s methods of critiquing Eisner’s work. “Dave would say, ‘I don’t think this transition works,’ or, ‘This character isn’t plausible,’” Kitchen explained. “He’d then say, ‘You can take this in several directions, but here’s what’s wrong with it.’ And Will would say, ‘Oh, I got it. Okay. Here’s what I’m going to do. What do you think?’ And Dave would say, ‘Well, you could take him in that direction, or you might throw the reader a curve and do this.’ They would have these conversations, and Dave would follow them up with letters.”

Over time, the two developed a very strong, trusting writer-editor relationship. Schreiner worked closely with Eisner on all of his longer graphic works, editing every one with the exception of

A Contract with God

and

The Plot

, Eisner’s final book.