Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants (14 page)

Read Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants Online

Authors: Claudia Müller-Ebeling,Christian Rätsch,Ph.D. Wolf-Dieter Storl

However, to the Church leaders and inquisitors struggling for power, these Goddess manifestations revealed themselves—reflecting the state of their own souls—as evil, dangerous witches who deserved to be destroyed. In Christian fairy tales Frau Holle eventually became the “the devil’s grandmother” or a witch with the poisonous apple; the apple was once considered a symbol of life and happiness. Her underworldly realm of light became a hot cave stinking of sulfur and pitch. In Russia she mutated into the frightening Baba Yaga with an iron leg; her magical house in the middle of the forest is built on a chicken leg and turns endlessly in a circle. She lies on the oven, her nose has grown into the ceiling, her snot pours over the threshold, her breasts hang over a hook, and she grinds her teeth (Diederichs, 1995: 37).

The elder bush (

Sambucus nigra

L.) was considered by the Germanic peoples sacred to the Great Goddess, who was also called Frau Holle or Holda. It was believed that the house spirits lived in the bush that grew near the house. It was considered the “farmer’s pharmacy.” (Woodcut from Otto Brunfels,

Contrafayt Kreüterbuch,

1532.)

Elder

(Sambucus nigra)

The names Hölderlin and Hollabiru are old German folk names for the devil, and are connected to the German name for the elder bush,

Holunder.

But linguists vehemently argue over whether the Holunder has anything to do with Frau Holle, the devil’s grandmother—that would be too romantic, too tacky. They derive the prefix

hol

from

kal

(black) and the suffix

der

from

tro

(tree); thus

Holunder

would be the black tree. However, those who have been able to retain a minimum amount of clairvoyance find the elder to be a kind of threshold, a gateway to the sort of transsensory, underworldly realm that has been traditionally associated with Frau Holle.

The Swiss plant esotericist René Strassmann is of the opinion that elder protects those living on earth from being attacked by the beings that live below the earth. Thus elder defines the boundary between the underworld and the middle world. Strassmann uses the wood, bark, roots, and flowers as incense for making direct contact with the shadow world (Strassmann, 1994: 153). The Germanic, Celtic, and Slavic heathens experienced elder in a similar way. The ancient Swedes sacrificed milk for the house spirits at the base of the “house elder”; the Prussians offered the earth spirit beer and bread.

In fairy tales Frau Holle is the queen of the dwarves and elves. It is no wonder, then, that those who fall asleep beneath an elder will soon sense the presence of gnomes, kobolds, and dwarfs. They will be encountered in a good mood or a grumpy one, or even as evil plague demons. Those whose third eye remains tightly closed will probably experience only headaches or body aches or become somewhat dizzy. The Swedes say that whoever sits under a flowering elder at dusk on midsummer’s eve will see the elf king and his court go by.

As protector of souls Frau Holle is also a goddess of the dead. Thus it becomes obvious that the little tree sacred to her played a central role in death rituals. The heathen Frisians buried their dead beneath the

Ellhorn

near their house, and their ancestors made crosses for grave sites out of an elder bush that had stood on the land of the deceased. It was considered a very good sign when the wood of such crosses budded once again. Then the dead could sit on it when they took their “vacation” on earth. In Tirol fresh elder branches are stuck in the grave to see if they will sprout, and elder flower tea is drunk at wakes. Until recently, in many places in northern Europe it was customary to bed the dead on elder branches. The coffin maker had to measure out the coffin with an elder reed, and the driver of the hearse was to use an elder switch for the horses. In England grave diggers carried some elder wood with them to protect themselves from questionable ghosts.

To the ancient Germans and Slavs, an old elder that nestled against the side of the house was considered the abode of family ghosts. It not only helped those who crossed over the threshold find their way to the realm of Holle, but it also helped those who returned from there. Thus the tree, called Frau Hylle or Hyllemoer (Mother Holle) by the Danes, was also connected with sexuality and birth. It plays an erotic role in folk songs:

Parsley, potherb grows in my garden.

[Name of the girl] is the bride, she shall wait no longer.

Behind an elder bush, she gave her love a kiss.

Red wine, white wine, tomorrow she’ll be mine.

1

The elder can also speak of separation and false love:

The stream runs and roars over there by the elder bush where we sat.

Like many bells ringing, as heart by heart lay, that you have forgotten.

—

FROM THE FOLK SONG

A

DE ZUR

G

UTEN

N

ACHT

[“G

OOD-BYE TO

G

OOD

N

IGHT

”]

In Thuringia during Whitsuntide boys placed elder sticks at the windows of the girls who were known to be somewhat easier. If the girls who were ready to marry wanted to know from which direction their groom would come, they gave the elder bush a good shake on Thomas Day (July 3). If a dog should then bark from any direction, that was the answer to her question. In the

Poetic Edda

it is said of elder tree that “the fruit of the tree of life should be placed in the fire for a woman with puerperal fever and delayed childbirth so that she can push out that which is concealed inside.” To build a baby cradle from elder wood was out of the question, because then the elder would take the baby back to the realm beyond. Also one should never raise a child with an elder whip; the child will neither grow nor flourish.

Elder is of a dual nature, like the Goddess of life and death: It is both white (the flowers) and black (the berries), and it is a medicinal plant and a strong poison. The house elder was a veritable pharmacy for the common people: From the flowers grandmothers brewed a tea that stimulated sweat and urine, which was helpful for flus, colds, rheumatism, measles, and scarlet fever. Modern phytotherapy has successfully confirmed the medicinal uses of the tea for hay fever and sinus infections as well. The grandmothers made an intestine-cleansing and -stimulating syrup from the black-purple berries. A hot, sweet elderberry soup was always part of the winter nourishment. Recent research has found immune-stimulating and nerve-strengthening activity in the berries. They are even used as adjunct therapy for cancer treatment, because the blue pigment has a positive influence on the oxygenation of the cells. Juice, syrup, and soup made of the berries help cure viral infections, herpes, and neuralgia; dried berries can be stored and then cooked when the flu or other illnesses are going around. The leaves, gathered in the summer, are made into lard-based salves for bruises, contusions, tumors, and chilblains. The cooked leaves are also placed on swollen or infected nipples. The bark is collected in the fall for its dramatic emetic and laxative effects. When the inner rind is scraped upward, it causes vomiting; when scraped downward, it brings on diarrhea. This “superstition” was not limited to Europe; Siberians and Native Americans also used it as a purgative when they wanted to cleanse their bodies. Their faith gave purpose to the physiological effects caused by the glycosides. As always, it is not merely the active ingredients that play a decisive role, but also the appropriate therapeutic word, the power of suggestion, that affects the outcome.

But this pharmacologically “sensible” use of elder was not only for health but also for magical purposes. Because the tree attracts negative energies, or “flying poisons,” and “uses them up” or guides them down into the underworld, all kinds of problems and diseases have been “hung” on it. Pus-covered bandages and cloth were draped on the branches. Teeth, hair, and fingernails were buried in its shadows in order to prevent magical misuse. The afterbirth of a calf was buried beneath the elder bush so that neither cow nor calf could be bewitched. The shirts of bewitched children were given back to the elder bush. The bathwater of small children was also poured out there.

To treat a fever, go to the elder bush on the night of the waning moon, wrap a thread around its trunk, and say, “Good day, elder. I bring you my fever, I tie it on, and now in God’s name I go.” Sometimes the sick would bend down a branch, saying, “I bend you. Fever, leave me now; elder bough, lift yourself up; swine fever, sit on top. I have you for a day; now you have it for a year and a day.” For toothaches the afflicted scraped his gums with an elder chip until the affected area bled. Then the chip was placed back on the branch from which it had been taken. As with the fever, the elder guided the toothache downward into the earth. Incidentally, it has also been reported that the woodlands Native Americans use elder magically to get rid of toothaches.

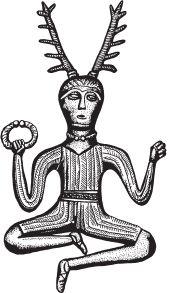

The horned god in a trance posture, depicted on the Celtic-Germanic Gundestrup cauldron.

To a tree as powerful and medicinal as this, the farmers have bowed down or respectfully lifted their hats. Arthur Hermes, the farmer-mystic from the Jura mountains in Switzerland, did so until his death in 1986. Nobody would dare to carelessly chop down or burn the wood of an elder. It was believed that the evil powers bound in the bush would attack foolish people and bring them bad luck or even kill them. Only widows and widowers were allowed to gather the wood and burn it, for they had already been touched by death. When cutting it down was unavoidable, the cutters exposed their heads, folded their hands, and prayed, “Lady Elder, give to me of your wood, so will I give you some of mine when it grows in the woods.” In the north in the Frisian Islands, permission to cut down an elder had to be obtained from the tree on the preceding full moon, and an offering was hung in the branches or buried in the roots. The cut branches could not be used in any manner, but had to be returned to the earth. Also elder should not be planted; the Goddess herself finds the right place for it to grow. This is usually not far from the house because elder loves to be near humans. When a house is vacated, it doesn’t take long before the elder that grew there dies.

The Germanic fertility god, Thor, drives his wagon, hitched to goats, through the air. When he hurls his hammer through the clouds he causes lightning and thunder. The thunderbolt rages lightning-fast to the earth, where it fertilizes the ground.

That the tree was an important ritual plant of the Great Goddess is demonstrated by the many different nursery rhyme versions of “Ring around the Rosy.” “Ring around the rosy; oh, we are children three; sitting’neath an elder bush, and calling hush, hush, hush!” The “Ring around the Rosy” songs children sing today are just as much an inheritance of archaic sacred ritual dances as hunting techniques like the bow and arrow are the legacy of Stone Age. Even the Christian missionaries were not able to shake the people’s respect for the tree. Although they said that the elder was an evil tree—torturers had beaten Jesus with an elder whip, and that is why, they said, the branches have cracks on their skin—in the end the tree was integrated into Christian mythology. Thus it is said that Mary dried the swaddling clothes of the Christ child on the branches of an elder under which she had found protection from a storm, and that is why lightning never strikes an elder. The traitor Judas hanged himself from the branch of an elder tree. In Allgäu the cross for the “palm” on Palm Sunday must be made only from elder branches. Certainly the sacred wood played a similar role in the spring processions and

Flurumg nge

a

of the ancient Celts and Germanic peoples.