Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants (17 page)

Read Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants Online

Authors: Claudia Müller-Ebeling,Christian Rätsch,Ph.D. Wolf-Dieter Storl

The powerful hallucinogen henbane

(Hyoscyamus niger)

was the most important ritual plant of the ancient Germanic peoples and was connected to the prophetic gods of the Celts, Greeks, and Romans of antiquity. It is one of the most important remedies in witches’ medicine. (Woodcut from Otto Brunfels,

Contrafayt Kreüterbuch,

1532.)

The great-grandmothers of Europe also harbor such secrets about fertility and birth. The Church brought about mistrust against the daughters of the sinner Eve, which escalated to paranoia during the time of the Inquisition. In theological writings, “woman is the gateway to hell, the way to licentiousness, the sting of the scorpion, a worthless gender.” Or else “sin comes from a woman … that is why we must all die” (Wolf, 1994: 59). In such an atmosphere feminine wisdom can be nothing other than satanic wisdom.

Weather Magic

Whether or not the fields and gardens will produce a bountiful harvest, whether or not the meadows will become green and the livestock will have enough to eat, is dependent upon the weather. Every culture has “weather-makers” who have a thorough knowledge of ritual techniques to draw down rain, banish lightning and hailstorms, or redirect the weather against their enemies. The practice of throwing burning wood or hot ashes into the air in order to subdue unwanted downpours is nearly universal.

The magic techniques that people use when the rain is absent and the ground withers are similar around the world. The weather shamans spray water, beer, or their own blood on the parched earth while singing magical songs that awaken the rain gods or change their attitude. In ancient Russia the rainmakers climbed up fir trees in the sacred grove. One of the magicians drummed on a kettle in imitation of thunder, another struck flint, sending sparks flying, and a third sprinkled water in all directions with a bundle of sticks (Frazer, 1991: 90). Often the rain is danced in by imitating the rhythm of raindrops with the dance steps. Usually the dancers are naked—they are outside of everyday humans, untouched by civilization, in a natural primordial state. Often the weather-makers are women, for they are “damper” by nature and closer to the water element and the moon. Among the southern Slavs a girl is chosen. She is then cloaked only in grass, herbs, and flowers, and she dances in circles through the whole village with a troupe of other girls. Every housewife must water her with a pitcher of water. If, in India, a drought lasts for a long time, naked women pull a plow at night over the soil—men are not allowed to be present.

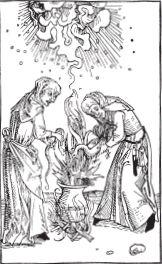

Witches brewing weather. Herbs and all sorts of other magical additives were stirred in the great cauldron. (From Ulrich Molitor,

Tractatus,

1490–1491.)

Today we find such superstitious practices humorous since we know the objective causes of drought and storms. Satellites mediate the state of the weather, and computers calculate the highs and lows. Today scientific experiments to control the weather are undertaken. All the same, Wilhelm Reich succeeded in causing rain in the 1950s with his “cloudbuster,” an apparatus that beamed orgone energy into the sky. And the United States, which like every superpower undertakes secret projects to control the world, was supposedly able to extend the monsoon season in Southeast Asia an extra week during the Vietnam war. (Incidentally, that would have been a classic example of black magic!)

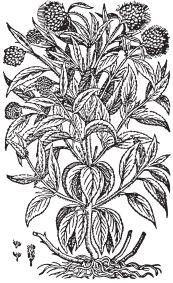

Hemp agrimony (

Eupatorium cannabinum

L.), also called water maudlin or water hemp, was used primarily for the liver, for the treatment of wounds, and for the healing of skin eruptions in folk medicine. In homeopathy

Eupatorium

is used in the diseases of the liver, spleen, and gallbladder. In German the plant was named

Kunigundenkraut

after Saint Kundigunde (tenth century), as she had withstood a trial by fire and had to walk through burning fields. (Woodcut from Tabernaemontanus,

Neu vollkommen Kräuter-Buch,

1731.)

Even though science makes a big deal out of it, shamans really can influence the weather because they are in contact with the spirits of the elements. Some skeptical ethnologists have had to acknowledge this as well, as did W. H. R. Rivers, who bade the newly converted natives in Malaysia to demonstrate a rain ceremony. At first they refused because the missionaries had forbidden it. Rivers explained to them that an exception would be made this time. The ritual was barely finished when it began to rain.

Naturally the Celts and Germanic peoples also had weather-making shaman women who performed their rituals in an ecstatic state and ritualistic nakedness. They beat puddles with sticks until the clouds formed. They brewed—similar to the witches in Shakespeare’s

Macbeth

—weather in a great cauldron in which they put herbs and other magical things. They stirred storm-raising energy with hazel wands. With henbane they woke up the lazy rain out of its sleep.

Heathen rituals such as these were practiced for a long time in rural areas. In the early eleventh century Burchard of Worms reported that a naked girl pulled a henbane plant—once consecrated to Belenos or Balder—out of the ground with the little finger on her right hand and then bound it to her foot. Then the rain-maiden was led to the river and splashed with water while prayers were sung.

Weather magic is also performed with other herbs—for example, hemp agrimony

(Eupatorium cannabinum),

also known as

Wetterkühl

(weather cool) or

Donnerkühl

(thunder/Thor cool). The plant is considered a stag plant because it is bound as sensitively to the weather as the stag is with his antlers. The abortifacient, diuretic medicinal herb was possibly once under the dominion of Cernunnos, the “lord of the souls”—the animal souls and also the cloud souls.

Because those who control the weather also control the harvest, and thus also control the heart and spirit of the people, the weather-disir were considered particularly dangerous. The

Indiculus superstitionum et paganiarum

, the previously mentioned handbook for religious informants, has heavy penalties for such

tempestarii

. The synod of Paris (892) judged: “When men and women who have committed such crimes [causing storms and hail] are discovered, they must be punished with unusual harshness, because they are not afraid to serve the devil completely openly” (Habinger-Tuczay, 1992: 278).

From then on women who were weather-shamans became monstrous storm-raisers,

Wolkenschieberinnen

(cloud pushers),

Schauerbrüterinnen

(shower-breeders),

Wetterkatzen

(weather-cats),

Nebelhexen

(fog-witches), or

Wolkentruden

(cloud spinners), who, it was rumored, had corrupted the crops with hail, tornadoes, and pestilence. The Christian defense against their machinations consisted of weather-blessings by a priest and the weather-ringing of the church bells.

Saint John’s Wort

(Hypericum perforatum)

Saint John’s wort is devoted to the sun like no other plant of the flora native to Europe. It usually grows in dry sunny places. The seeds germinate only in sunlight. The effects of the sun are revealed in the intensive flowering, in the sturdy, well-structured stems, and in the many small oil glands that look like perforations in the petals and leaves. The hypericin oil is really transformed sunlight.

Saint John’s wort is so saturated with light that it can pass its light effects on to other organisms. Light-skinned ruminants such as sheep, pigs, and cattle can develop photosensitivity; infected, inflamed skin; and stomach cramps when they eat the herb and then go into direct sunlight.

The plant also demonstrates a very definite light effect on people who take it as a tea. Recently

Hypericum

has been used in the United States for the treatment of AIDS (Foster/Duke, 1990: 114); this makes sense, not only because many infected by HIV suffer from depression (which Saint John’s wort can alleviate), but also because of the danger of becoming infected with candida yeast. HIV patients die not from the virus but usually from a complete infection of the lungs and blood with yeast. Candida is an opportunist, and when the immune system is compromised the fungus spreads from the intestines to the reproductive organs, to the lungs, and finally to the blood. Yeast, such as candida

,

cannot stand any sunlight. It needs a dark and damp environment. Because a plant like Saint John’s wort is enriched so much by the sun, it is an appropriate remedy for yeast infections.

Saint John’s wort also has an inner and spiritual light-bringing effect. Saint John’s wort radiates the summer sun into the darkest corners of the soul. The tea—a cup drunk every day over a period of a few weeks—lightens dark moods and chases off melancholy, fear, and depression. Chemists believe that the red pigment hypericin, a phenolic compound, is responsible for the euphoric antidepressant effect.

It is interesting to take the drug (the tea) and to observe the effects in meditation following the homeopathic method of proving. The entopic phenomena of light, the clouds, and lightning that normally appear behind closed lids are unusually bright. Colorful, nearly gaudy light forms ascend, gain in radiance, and freeze suddenly in rigid geometric patterns. Thus, these light phenomena playing on the eye’s interior mirror the external appearance of the plant.

The ascending cloudlike entopic light phenomena, probably the result of electric nerve impulses deep in the eye socket, are the raw material from which the images in dreams and visions are woven. Usually we do not notice them as we glide into a dream and lose our consciousness of external reality. But if attention is meditatively placed on this seam between waking and dreaming, then one will become aware of such “light clouds.” If grim images resembling dark and threatening storm clouds rise in front of the spiritual eye, these will be absorbed by the power of Saint John’s wort’s light and will be organized into beautiful, if somewhat rigid, patterns. The plant “creates itself” in our soul; it influences the sunlike energy of forms. Fearful and melancholy thoughts can barely keep spinning under the influence of the

Hypericum

drug.

Of course, this psychoactive effect did not remain hidden from the old herbalist women. The name

hypericum

comes from the Greek

hyper,

meaning “over,” and

eikon,

meaning “picture.” Thus

Hypericum

lifts the human spirit over threatening internal images, over the diseased imagination. Medieval doctors called the plant

Fuga

daemonum,

which indicates that it forces demons to flee. Paracelsus considered Saint John’s wort to be “an

arcanum,

a universal medicine of greatest effectiveness, a

monarchei,

in front of which all must bow.” In the language of signatures the small veins in the leaves denote that the herb chases off all

phantasmata

around and beneath humans. By

phantasmata

Paracelsus meant “diseases without body and without substance”—in other words, “imagined voices, insanity and lunacy” (Pörksen, 1988: 75). “So that the heavenly influence works against the phantasmata, the plant must be collected in correspondence with the path of the stars,” when Mars, Jupiter, and Venus are in good aspects, but not when the moon is full. The medicinal plants should be gathered at sunrise, with the harvester facing the sun. Paracelsus wrote, “The herb should always be carried, underneath the hat, on the breast, or as a wreath in the hand, and smelled often, placed underneath the pillow, placed around the house or hung on the wall!”