Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants (51 page)

Read Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants Online

Authors: Claudia Müller-Ebeling,Christian Rätsch,Ph.D. Wolf-Dieter Storl

The sixteenth-century encounter of Paracelsus with the accusation that he was a black magician demonstrates how reprehensible it was considered to turn directly to nature with conjuring formulas and to therewith violate divine laws.

If I had otherwise invoked a spirit, a person, an herb, a root, a stone, or anything like this with its holy name, then one could say with truth and righteousness that I had taken the name of God in vain and therewith angered God, but not before. Let the theologists and sophists say about this what they want, the truth shall not be any different, even if they go against me severely and call me a sorcerer, a magician, an abuser and breaker of divine law, I shall not pay heed.

31

Paracelsus got off the hook one more time. But Giordano Bruno, who was burned at the stake as a heretic on February 17, 1600, on the Campo de’Fiori in Rome, did not. When one reads his statements about magic and magicians in the context of the phobia of all thoughts that did not originate in the moral-theological breeding ground, one must wonder how he was able to live to fifty-two years old in such a climate of mutual denunciation (to which he ultimately fell victim). In his tract

On Magic,

written between 1586 and 1591, Bruno planted the term

magician

in a historical process of development between the wise and the miracle workers. He called such a person

malefic

“when he tends toward evil. When he tends toward good, he should be considered amongst the practitioners of medicine.” And when he causes death, he should be called “poison magician.”

The Christian dignitaries, however, could not care less about such differentiation. According to Bruno they brought the term

magician

to discredit: “For this reason his name does not sound as good to the wise or grammarians, because certain cowl wearers make demands of the term magician. Such a Capuchin monk was the author of the ‘Hexenhammer.’”

32

What an appropriate evaluation of heresy!

From today’s perspective it seems very strange that someone such as Paracelsus, who turned to the people with the intention to heal and who searched for medicines in nature, was accused of sorcery and witchcraft—and that

medicine

and

magic

were named in the same breath. The logic behind this is as simple as a stereotype: It is not the plants themselves that are sacred but the spiritual principle that created them. To call plants “by their sacred names” meant to criminally confuse them with God. God rules over life and death, and those who claim to rule over therapies, medicines, or recipes to fight disease or to lengthen life are ultimately in league with the devil. Those who are struck by disease are being punished by God for their sins, and if they heal, they owe their life to God’s will and their atonement of their sins. This concept can already be discerned in the fourth century

A.D.

in the writings of the Church theoretician Athanasius, who praises Saint Anthony thusly: “The sick he convinces to be patient and to understand, and that the healing did not come from him at all, but from God alone, who causes it, when and on whom he so desires.”

33

In

The Dream of the Doctor

Albrecht Dürer shows unequivocally that it is the bat-winged devil who uses a bellows to instill ideas about the healing powers of nature in the physician. The Venus/Nature who extols her gifts looks like a naked witch. (

Traum des Doktors

, copperplate, Nürnberg, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, 1498–99.)

Paracelsus takes what we would consider a more enlightened position. When he spoke about medicine in his

Astronomia magna

(chapter 10, p. 239), he wrote that having the courage to use this healing art resonates with God, for God himself is the physician and whether the person gets healthy or stays sick is in his hands.

34

Eventually, in the nineteenth century, Jules Michelet attacked this attitude of the Christian Church when he wrote that during the time of the witch trials life was considered to be merely a test given to humans. Therefore people were encouraged not to harbor any desire to prolong their lives. Within Christian circles medicine was viewed as simply a properly resigned attitude to await death and even hope for death. But who, then, could be a healer? Michelet says, ironically and provocatively, “It was a broad field for Satan. As he was physician and healer of the living and furthermore even their comforter.”

35

That he thoroughly hit the nerve of the early modern era with these surprising words was confirmed by Martin Luther. The turbulence of the early sixteenth century can be traced back to the effects of his Reformation: “We are all subordinate to the devil with body and soul as guests in this world, whose Lord and God he is himself.” Thus those who attempt to exercise a certain amount of control over their bodies can, in a magical sense, come only from “bad parents”; in other words, they have made a pact with the devil, who has given them unusual abilities.

A winged devil shakes the repulsive disease over a syphilis victim. The sores rain on the sickbed from a cornucopia that has been perverted into Pandora’s box. (Woodcut, Zentralbibliothek, Luzern, 1512.)

Medicine, as it was practiced in the folkways of the countryside, was connected with divination, namely the prophetic awareness of the origins of disease and their therapy. A healer was often a seeress who determined life or death with her recommendations for the sick person. As long as the healers used their knowledge for soothing or healing the sick, people happily consulted them and looked past the ecclesiastical restrictions of visiting such wise women. But if the disease got worse or the afflicted person died, people were all too quick to blame it on sorcery.

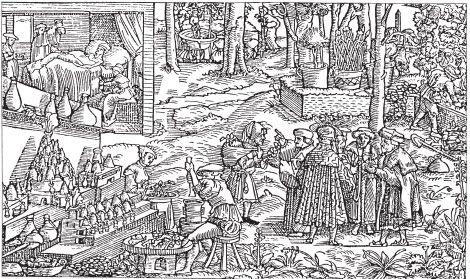

On a woodcut from the 1578 edition of Lonicerus, women are shown playing a variety of roles in the pharmaceutical process, from gathering the medicinal plants to their application in the sickroom. (Lonicerus,

Herbar/Kreüterbuch

)

Many authors, and in particular female writers, who have dealt with the themes of the witch craze or the witch trials have pointed out the central role of the woman in the folk medicine of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Based on their own experiences of giving birth, women have always worked as midwives and passed down their knowledge of nature from generation to generation. The woman’s knowledge of physical processes and medicinal herbs has always gone hand in hand with magical formulas that chase off disease demons and encourage the healing process on the plane of thought.

36

From a feminist perspective the competition between the healing abilities of the women, which were based on traditional experiential knowledge that had been handed down over generations, and the physicians, who had been trained at the university and who based their knowledge on written documents, represents a significant factor in the witch trials.

37

But others came to the conclusion that this competition should not be given too much weight, as the doctors worked more often with the nobility and in the cities and for this reason barely saw the women healers, who were consulted by the country people, as competitors. Besides, upon closer examination one sees that healers and midwives were not well represented in the horrifyingly high number of women murdered from the fifteenth through the eighteenth centuries.

38

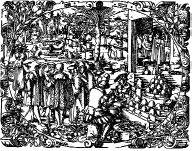

On the frontispiece of the 1679 edition of Lonicerus the woman gathering herbs and the female pharmacy assistant are missing. Only the physician stands at the sickbed.

The competition theory is not so easily laid to rest, however, as can be demonstrated by comparing images from different editions of the

Kreüterbuch

of Adam Lonicerus (1528–1586) (see illustrations above). In a woodcut from the 1578 edition the artist depicts the entire pharmaceutical process, from finding the plants to their processing and utilization. In the background are woods in which a well with a heathen figure is found and where an herbalist is gathering plants. To the right of this a gardener cultivates certain plants. In the foreground a person (whose gender is not clearly identifiable) brings the collected material to a group of men, whose gestures and garments distinguish them as educated. The plants are then prepared by a female assistant and ground in a mortar by a pharmacist. The vessels in the left foreground indicate that the herbs are being prepared for distillation. The use of the preparations, in the middle left of the print, brings an end to the process. Three people are gathered around a sickbed: a woman who grinds plant material, a doctor who checks the dosage (which he administers to the patient), and a female assistant.

This simplified composition of the medicinal garden, which is obviously derived from the more complex picture below, includes only the scholar, who in this image has been turned into a plant gatherer. (

Grete Herball,

London: Peter Treveris, 1526.)