Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants (54 page)

Read Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants Online

Authors: Claudia Müller-Ebeling,Christian Rätsch,Ph.D. Wolf-Dieter Storl

Rübezahl: Herbalist and Weather God

Besides interceding in matters of human health, another way in which folk medicine and shamanism were seen as interfering with the natural order of things was the practice of weather magic. In court witches were accused of destroying the harvest with hailstorms and stopping the milk flow of the neighbor’s cow. The connection of shamanic and folk-medicine ways with weather making offered the Christians someone besides God to blame for interventions in the natural course of life. When the weather is in harmony with the needs of humans and when it is beneficial to the harvest, then there is no need for an explanation—for God, in his eternal goodness, reveals therein his fondness for the creatures he has created. But when man is at the mercy of the forces of nature he encounters powers that the nature spirits were once held responsible for—a concept that has survived into present times in rural areas, although it has been long since layered over with Christian interpretations.

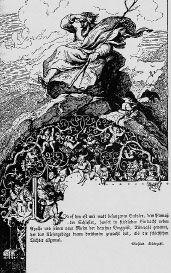

Much less demonic and more like an Old Testament father god or Zeus, the masculine weather-spirit Rübezahl gazes from the heights of the mountaintops, from “the Silesian Parnass.” His trident is also known from Neptune and Shiva—and also from the witches. The ravens and the root manikins belong to Rübezahl’s domain. (Illustration by Ludwig Richter, 1848.)

Examples of the deeds of mountain and wood spirits, of water nymphs and field spirits, in which the polytheistic spiritualization of nature has survived, are found in many sagas. The stories about Rübezahl, the weather god and spirit of the Silesian mountains, preserve some of these ancient concepts. His name contains not only the words

Rüben

and

zählen

(root counting), but also the Old German word

Zagel

(tail) and the modern German word

Rübe

, which means “root,” “turnip,” or “fleshy taproot.” From these terms the power of Rübezahl, lord of the medicinal roots the mountain inhabitants can benefit from in the event of illness, can be elucidated. But the name also offers clues for understanding Rübezahl as an earth spirit with a tail—in other words, a field demon.

It was reported that even as late as 1814 the inhabitants of the Silesian mountains made pilgrimages to the summit of the mountain, near the source of the Elbe River. There they sacrificed black roosters and hens and said prayers and invocations to Rübezahl in order to pacify the mountain spirit and divert the path of the threatening floodwaters as they roared down from the mountain. The people brought springwater and herbs and roots back home with them, and used these to wash their cows and stalls.

With regard to Rübezahl, Johannes Praetorius (1630–1680), whose reports about the witches at Blocksberg have been passed down, wrote:

There was a root-man who always brought herbs and roots into the pharmacies. The same man knew the way to the spirit of his root garden; it was called the devil’s ground. Therein he had his garden and his special herbs and roots. Not just any man received them from him, the spirit would only give them to those with good intentions. If someone attempts to get them from the spirit through violence or conjurations, he must be perfect in his work, or he will have his neck broken, or otherwise great bad luck will befall him. (

Historien von Rieben-Zahl,

1738).

A conjuring spell from 1630 was quoted by Klapper (1936) as an invocation to Rübezahl: “You great man, you doctor, come before us! He who honors you awaits your presence.” Around 1566 the Heidelberg theologian David Pareus reported on an encounter with a weather spirit who surprised him with a tornado while he was walking to a white-water source: “The people attributed [it] to an evil spirit … which lurks in the lower valleys and often disturbs the water. The inhabitants call it

Riebenzahl

.”

57

Moritz von Schwind (1804–1871) depicted Rübezahl as a wood spirit with a red beard, in the same sort of environment that witches are found—a forest with knotted trees and flaming red fly agaric mushrooms (in the collection of the Bavarian Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Schack Gallery, Munich).

In connection with the thunderstorms the so-called witches’ brooms or thunder-brooms are growths which are similarly nestlike and as a rule are caused by parasitic mushrooms on white fir, birch, and cherry trees. People of earlier times liked to attach them to the house gables for protection against lightning and fire. From the symbolic character of such botanical malformations—which is what the witches’ brooms are—the folk superstition sought to derive a connection to lighting. The “broom” is firstly a symbol of separation, of air and of heaven’s purifying lighting. Thunderclouds often appear broomlike and “sweep” the sky—the sea people call the west wind “heaven’s broom” (Engel, 1978: 60).

Seeress and Goddess of Fate

During the time of the great witch hysteria, the churches—both Catholic and Protestant—negated all possibilities for humans to exert a positive, fertile influence on natural occurrences. Thus in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries the clergy demonized the practices of conjuring natural forces and divining from the signs of nature, practices that were still alive in broad segments of the rural population.

In heathen times the Germanic peoples were more likely to know prophetic women than men. They practiced weather oracles, oracles of the bridal night, and water divination. But Church leaders interpreted such methods as human attempts to become all-knowing, like God. In the second half of the sixteenth century soothsayers were “shit out by the devil into the world because the humans are brazen and want to know more than they should,” according to the Heidelberg rector Wilcken. He also warned, “We are created by God, and it has been preordained by him what we can know” (Wolf, 1980: 473).

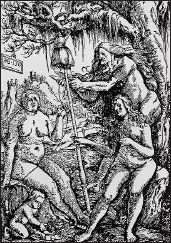

In his allegorical copperplate engraving 1505–07 Albrecht Dürer represents Aphrodite Epitragidia, “she who rides on a buck,” as an old witch with love gods. In her arm she holds a distaff.

In one small detail the painters of witch images have left us a clue as to why the people of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries perceived the activities of witches as being an offense against the divine order. With surprising regularity a distaff can be found in pictures of witches. It first appears in the hands of a haggard witch in Dürer’s 1505 allegory (see illustration at left), which we shall study in greater detail below. We also notice it in the context of the herb woman of Hans Weiditz (see illustration on page 151). And in the washed pen-and-ink drawing on page 177 by Jacob de Gheyn II (1608) a witch in the left foreground holds a distaff clamped between her legs. An almost magical force seems to emanate from this distaff, for hailstorms and thunderclouds are brewing in the direction in which it points.

Is the distaff a tool of the devil, with which the witch draws her energy for black magic? And could these images be saying that in the hands of witches harmless objects can easily be turned into dangerous weapons? Could this tool, which was found at that time in all homes for spinning yarn, indicate that any normal farm wife or city woman could be a witch? A distaff in a single-page woodcut by Hans Baldung Grien, dated 1513 (see illustration on page 178), suggests divination and the three goddesses of fate. Grien has placed three women in front of a leafless lichen-hung tree whose barren branches spread out across the scenery. The youngest, with long wavy hair, sits on a tree stump, holds the distaff, and looks at us with a mischievous grin. Behind her the eldest, with her full loose hair contrasting with her emaciated body and the haggard lines on her face, bends forward to the bushel of hemp behind the child. With a large pair of scissors she cuts the threads, which the motherly plump woman, who wears the typical old German bonnet of a married woman, is spinning. She sits on an embankment across from the young woman, who like the elder also cuts the strings of life; at her feet a small naked boy picks a flower. The group, in a shady valley in front of a sunny, hilly landscape, could also be a depiction of the different stages of life—childhood, youth, maturity, and old age. Their nakedness, the enigmatic expression of the youth, their long loose hair, and the dead tree are all reminiscent of witches.

Indeed the ability of witches to influence health, life, and death—and therewith the threads of life—is connected thematically to the Greek Moirai (the Roman Parcae). In classical mythology they were associated with grim spirits of the dead as well as with divinatory spirits of birth, and had—as daughters of the almighty sky god Zeus and Themis, the all-knowing earth goddess—responsibility for overseeing the orderly process of the universe. The Moirai’s influence on the human world—for which Homer repeatedly used the metaphor of spinning a thread—disappeared from human awareness. Hesiod describes them in the most ancient sources as “daughters of the night.”

An Orphic hymn reveals how the classical man characterized these goddesses of fate, who spin the threads of life and, at the given time, cut them:

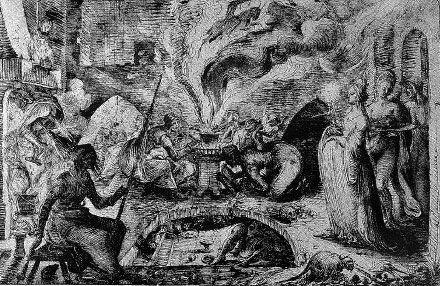

Jacob de Gheyn II disseminated extremely grisly witch scenarios. This drawing, called

Witches’ Sabbat,

includes the witches’ cauldron, which escapes through the chimney, and visibly farting witches. Also depicted are skulls and bones and corpses, which are taken to the cellar to be stored for future procedures. Witches from higher levels of society who carry, among other things, the decapitated head of a child also appear. In addition, in the left foreground is a witch with a distaff. (

Hexensabbat,

washed pen-and-ink drawing, Berlin, Museen preußischer Kulturbesitz, Kupferstichkabinett, 1608.)

Boundless Fates, dear children of dark night, hear my prayer, O many-named dwellers on the lake of heaven where the frozen water by night’s warmth is broken inside a sleek cave’s shady hollow: from there you fly to the boundless earth, home of the mortals, and thence, cloaked in purple, you march toward men whose aims are as noble as their hopes are vain, in the vale of doom, where glory drives her chariot on all over the earth, beyond the goal of justice, of anxious hope, of primeval law, and of the immeasurable principle of order. In life Fate alone watches; the other immortals who dwell on the peaks of snowy Olympos do not, except for Zeus’ perfect eye. But Fate and Zeus’ mind know all things for all time. I pray to you to come, gently and kindly, Atropos, Lachesis, and Clotho, scions of noble stock. Airy, invisible, inexorable, and ever indestructible, you give all and take all, being to men the same as necessity. Fates, hear my prayers and receive my libations, Gently coming to the initiates to free them from pain.

Hans Baldung Grien depicts the three Parcae, or the three goddesses of fate, as witches who sever the threads of life from the distaff. (

Die drei Parzen,

Einblattholzschnitt, 1513.)