Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants (58 page)

Read Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants Online

Authors: Claudia Müller-Ebeling,Christian Rätsch,Ph.D. Wolf-Dieter Storl

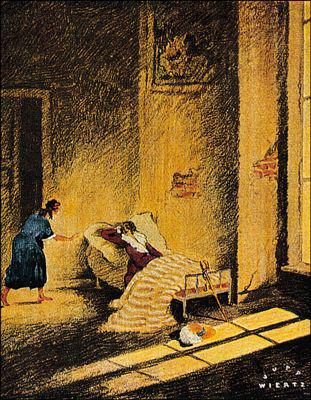

Around 1870 Robert Bateman (1842–1922) depicted the unusual magical practice of pulling the capricious mandrake root from out of the ground beneath the gallows. Like the three Norns, the women use threads and gazes of invocation to help them in their operation. (Wellcome Institute Library, London.)

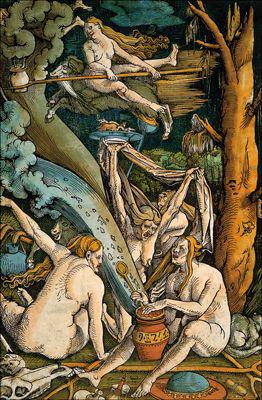

Hans Baldung Grien disseminates the world of the witches in great detail: The witches’ cauldron, billy goats, a cat, phallic sausages, skulls, bones, and profaned objects from the clergy, such as the pilgrim’s hat in the right foreground, are depicted here. With this painting the artist was duty-bound to the existing ideas of the time and based the motif on predecessors such as Albrecht Dürer. He had considerable inFluence on the concept of the witches’ sabbat with this chiaroscuro woodcut

Preparation for the Witches’ Sabbat

(1510), which was widely spread and often copied in numerous variations. (Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco.)

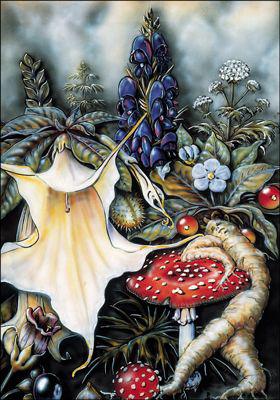

Fred Weidmann, a painter who lives in Munich, collected the most important European psychoactive plants on this airbrush painting: Fly agaric, mandrake, angel’s trumpet, monkshood, hemp, belladonna, and poison hemlock.

Goddess Nature

Eventually the personification of nature, an image that is surprisingly rare in Western art, was pushed into an ever-increasing demonized realm beyond. The beginnings of this process are depicted in an example from the illustrations in

Medicina antiqua (Codex vindobonensis:

93) from the early thirteenth century (see illustration above). The codex, which was assembled in southern Italy, contains an illustration showing an invocation of the divine Mother Earth. She stands in classical clothing on the banks of a river in which the river god Neptune can be seen sitting with his trident on a snake. Mother Earth holds a cornucopia in her arms and is surrounded by stylized palms and fantasy plants. In front of her is a Roman supplicant. The fifty-one-line invocation on the back side of the paper was destroyed in the Middle Ages by the hand of a monk and “corrected” so that the masculine god is in the place of the feminine goddess Gaia; thus the invocation no longer says, “Sacred Goddess Earth, bringer of the natural things …” but, “To the Sacred God …” (Biedermann, 1972: 79).

The Witch As the Temptation of Saint Anthony

The transformation of the goddess of fate into the disease-bringing witch has already been discussed. This same connection between disease and fate can be seen in the Germanic goddess Holda, who has been preserved as Frau Holle in fairy tales (c.f. Rüttner-Cova, 1988). Like her sisters Venus and Isis, Holda, who is also titled Queen of Heaven and who ruled over household matters (one of her symbols is the spindle), was demonized and cast out as a witch. As a rule I think it can be safely said that most of the heathen goddesses eventually “end up” identified as the vilified and disparaged witch.

69

Beneath these demonized appearances it was actually the goddesses’ true divine nature that led Saint Anthony into temptation.

What does Saint Anthony have to do with witches? First, a brief look into his life.

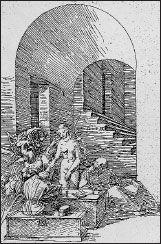

Saint Anthony is tempted by a Venus-like witch and by Pan, who has been turned into a bat-winged demon with panpipes, in this 1515 illustration by Albrecht Dürer.

Anthony’s existence has been historically substantiated. He lived in Lower Egypt during the third and fourth centuries C.E., at the temporal threshold between heathendom and Christianity. He was the son of well-to-do farmers of Egyptian origin. When he was barely twenty years old Anthony gave away his inheritance and went to live an ascetic and solitary life in the neglected ruins of ancient Egypt. He spent his whole long life on the run, dying in 356 in the biblical era at the age of 105. He moved ever deeper into the desert, fleeing the streams of disciples willing to be ascetics who stormed his settlements with questions. They wanted to learn from him how one could survive without satisfying the basic physical needs of eating, drinking, sleeping, and sex.

These early Christians were convinced that only such a life would really be pleasing to their god. They had many vigorous arguments with the Egyptian, Greek, and Roman heathens, and tried to convince them that neither nature nor their gods were sacred, but that only the Christian God and the spiritual principle were valid. With such an attitude, which allows no other gods and truths to exist, one seldom makes friends. The Roman emperor who ruled Egypt during that time violently persecuted the Christian sect.

Perhaps this is the reason why Antonius Eremita fled from worldly life with his disciples, even though Athanasius, the author of his life story, depicted Anthony’s flight more as a steadfast stand against the seductions of power and wealth. However, in the decayed temple sites where Anthony settled, he encountered the divine ancestors of his Egyptian past. He saw them as monsters with pointed beaks, sharp claws, and fangs who attacked him. Anthony, as the legend tells, did not allow these confrontations with his demonlike ancestors to deter him from his own still-youthful belief. But it was precisely the ancient Egyptian gods—excuse me, Anthony’s demons—who made him famous and holy. Athanasius took care of this when he wrote the life story of the exemplary hermit from Egypt just after Anthony’s death in 356, so that all Christian monks could follow his example. With stereotypical declarations of war against heathen ways of thinking, Athanasius hammered out sentences such as the following:

The demons, who the heathens consider as gods, are not gods; yes, that they [the Christians] step on them and torture them, because they are the seducer and destroyer of man—in Jesus Christ, our Lord, who is splendid in eternity. Amen (Athanasius, 1987: 118).

But what has this got to do with the temptations of Saint Anthony, and what does the witch have to do with him?

According to modern psychological theory one stays “right on the heels” of those very things one most suppresses. Personal desires take on seductive forms, and what one is secretly afraid of manifests in frightening images. Anthony, alone in the unvarying desert without enough to eat, always on the edge of thirst, and without the distraction of any sensuous desire, was entirely subject to his inner world. All of the seductive women he has spliced into his concept of desire visit him in his desert settlement. In his withdrawal from desire the fantasies of boundless power, endless wealth, and notions of his own greatness pressed to the forefront of Anthony’s delirious brain. Eventually all of the falcons, cows, and crocodile-headed gods of the ancient Egyptian pantheon that he could see in the bleached frescoes around his settlement became animated.

We don’t know what really happened. But Anthony’s friend, the bishop Athanasius of Alexandria, in his hagiography of the legendary hermit convincingly secured the belief that Anthony was victorious over all of these challenges and continued on with his unshakable convictions. Athanasius interpreted the visions of the canonized Anthony as being temptations of the devil, who tested him in the form of seductive women and hideous demons in order to deter him from the path of righteousness—in other words, from the path of Christian belief.

This legend of the saint exerted a substantial influence on Western spiritual and cultural history. Whenever and wherever Christians are confronted with opinions and concepts of reality that their church has not blessed, they people their surroundings with devils, demons, and witches. As only one single god and one single world were canonized or permitted, the devil became the perfect sorcerer and transformation artist and manifested in an endless number of forms. He demanded his Christian opponents recognize his true diabolical nature behind the facade of beautiful women, eloquent monks, followers of different faiths, and even in cat’s fur and raven’s feathers. Thus the artists, particularly in times of unrest, captured in their pictures the various tempters and temptresses as Jews, Muslims, Cathari, Waldenses, or reformed Lutherans. True to the legend of Anthony they place the usually frightened and cowering saint on the borders of the paintings and confront him with the demonic activities of hybrid creatures in whose bodies all that man is afraid of is unified. They present Anthony with toothless women and, more often, richly dressed or seductively undressed women. These temptresses were the diabolic embodiment of the seven deadly sins, particularly of lust and pride. In them the heathen goddesses Freya, Aphrodite, Diana, Artemis, and Hecate rise again.

Hieronymus Bosch (c. 1450–1516) was the first to recognize that all of the inner images that Christianity suppressed were still preserved in the form of the witch. He integrated the witches’ sabbat in his peculiar depictions of the temptation of Saint Anthony, which were created in the period between 1475 and 1500 (they are difficult to date). The great impact of his creation of monstrous hybrids—in which not only actually existing animal and plant species were paired with his newly invented creatures, but pots, jugs, musical instruments, and other lifeless objects were also transformed into body parts—can be seen in his many imitators, the most enthusiastic of them being Pieter Brueghel the elder.