Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants (59 page)

Read Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants Online

Authors: Claudia Müller-Ebeling,Christian Rätsch,Ph.D. Wolf-Dieter Storl

In Bosch’s puzzling pictorial worlds that have led authors to interpret the most varied of meanings from the paintings without finding the key to the answer, the artist depicts, as Frater José de Siguenza put it, “humans as they truly are inside.” Although I do not want to go extensively into the heretical contents of his pictures at this point, a brief description of one of them may help to clarify the question of how such blasphemous altar paintings by the Brabant artist from’s Hertogenbosch might actually fulfill Frater Siguenza’s contention of the painter’s ability to capture both the angelic and the demonic components that combine in every human being.

At this point I would like to describe Bosch’s famous Lisbon triptych,

The Temptation of Saint Anthony,

thought to have been created after 1490.

70

As in all depictions of the temptation, at first it is difficult to make out the hermit among the turbulence. The saint is found kneeling on a small wall in a half-destroyed ancient tower, with his gaze on the observer. He and the strange entourage surrounding him are depicted on a bridgelike plateau. A bearded man with a cylindrical hat, red clothing, and a severed foot who has spread a cloth out in front of him leans on the opposing wall—he has apparently fallen sacrifice to the so-called Saint Anthony’s fire.

71

Except for his head, turned out of the painting toward the viewer, Anthony is facing a crucifix in the middle of the dark tower. Next to the panel is the martyred physical shell of the resurrected, self-manifested being—the man on the cross. To the left, near Saint Anthony, is a woman in contemporary clothing whose body turns into that of a pointy snake: the caricature of a false believer, a hypocrite. She passes an old nun a jug of red wine—the Eucharist blood of the crucified. A procession of three strange women is next to the kneeling woman. One of these three “priestesses” turns to Saint Anthony with a piercing gaze and passes him a mug. She wears helmetlike head protection, out of which snakes slither, and a long-sleeved dress. To her side stands an unusually pale woman wearing an oriental-styled, thorn-decorated hat, on which is fixed a veil that partially covers her face. A bizarre object of worship is held in the air over a round table. The table is approached by a crawling cripple, a knight with a mandolin, and a hedgehog head on which sits an owl. The end of the procession is made up of a black man with red cardinal-like robes who is holding the bizarre object: a plate, on which sits a frog holding an egg in the air.

72

Wilhem Fraenger interpreted this whole symbol-laden and puzzling scene as a “black mass.” He characterized the three women as “snake, moon, and swamp women,” whom he places in the mythological vicinity of the Egyptian frog-goddess of Antinoë, Heket, the primordial mother of being, who can be traced back to the four primordial gods of Egypt.

73

Whether or not one agrees with this interpretation of the painting, in the context of this book the inclusion of the witchlike temptresses in

The Temptation of Saint Anthony,

and the heathen practices that can be deduced from them, is of importance. Temptresses had already been depicted in earlier examples of this genre; as a rule they symbolized Luxuria, whose “diabolic” nature can be deciphered by her bat wings and clawed feet. But Bosch was the first to connect the temptress with ritual practices of heathen origin, which were contested by the Church for being heretical. “Bosch delivers a thoroughly un-simple, wrested from all conventions confessional picture, whose polemic excessiveness dipped the virtuous stuff into a witches’ cauldron.”

74

On the eve of the Reformation the representatives of the Christian church vehemently declared themselves for the destruction of heathen customs.

75

After Bosch, witchlike temptresses are found in countless examples of Dutch art of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries—the period when this theme reached its apex. Integrated into the world of the ascetic recluse, women seduce Anthony in their witches’ kitchen, in rock archways, or during the witches’ sabbat in isolated forests. In pictures by Joachim Patinir, Cornelis Massys, and Jan van de Venne, witchlike old women with bared breasts and distorted expressions appear as modestly clad matchmakers or as naked temptresses, as well as in other guises. Here, too, they offer the saint the apple of Eve that caused the fall of man as believed by the Christian world, or else they offer him heathen idols, sacks of gold, or plates of delicious food. All heathen concepts of the sensuous joy of life embodied by their goddesses were regarded not only as threatening Saint Anthony but also as corrupting all of Christianity; they all combine in the image of the witch.

Only in the nineteenth century did the once divine nature that had been vilified and made diabolical reenter consciousness. The writer Gustave Flaubert, who fashioned a character for a novel out of Anthony, gave the ascetic memories of his encounters with gods and goddesses such as Isis, whom he originally experienced as nothing more than horrible demons. He then recognized these figures for what they represent—Egyptian gods—although in an alien animal form: “When I lived in the temple of Heliopolis, I often looked at the pictures on the wall—scepter-carrying vultures, lyre-playing crocodiles, snake bodies with men’s heads, cow-headed women who worship ithyphalic gods.”

76

Medicinal Plants for Saint Anthony’s Fire

77

Blind nettle (

Lamium album

)

Bulbous buttercup (little rose of Saint Anthony

Ranunculus bulbosus

)

Clover (

Trifolium repens

)

Couch grass (

Agropyrum repens

)

Cross-leaved gentian (

Gentiana cruciata

)

Cypress grass (

Cyperus fuscus

)

Long plantain (

Plantago lanceolata

)

Plantain (

Plantago major

)

Red poppy (

Papaver rhoeas

)

Spelt (

Triticum speltha

)

Swallow’s wort (

Vincetoxicum officinale

)

Veronica (

Veronica chamaedrys

)

Vervain (

Verbena officinalis

)

Water figwort (herb of Saint Anthony,

Scrophularia aquatica

)

Mathis Gothart-Nithart, known as Matthias Grünewald (c. 1455–1528), created a panel with three sides that is dedicated to Saint Anthony. The piece was commissioned by the Antoniterhospital [St. Anthony Hospital] in Isenheim around 1512.

The Temptation of Saint Anthony

is the most impressive of the plates. On it are not only a demon horribly attacking the saint, but also, to the left and below, a victim of Saint Anthony’s fire with a bloated stomach. The fantastic scene gives the impression of originating in a nightmare. On the left-facing side Grünewald placed the meeting of the two hermits, Anthony and Paul, who find themselves in a conversation in a wooded environment. Wolfgang Kühn made a botanical identification of a total of fourteen medicinal plants that are to befound on the hermit’s plate (see page 188), and eight were listed in herbals of the time as remedies for Saint Anthony’s fire. The other six were used in the treatment of “burns, infected wounds, and old sores.” Kühn assumes that the fourteen plants that were represented were also the ingredients of the Saint Vinage vinegar or the Saint Anthony balsam (Kühn, 1948: 330f.), for which the Isenheim order was famous. Some of the plants—for example, vervain

(Verbena officinalis),

blind nettle

(Lamium album),

corn poppy

(Papaver rhoeas),

and one of its relatives, the opium poppy

(Papaver somniferum)

—have been identified. All of these plants are closely associated with witches—the blind nettle even has witches (

lamia

) to thank for its Latin name.

Saturn: Master of the Witches

The person of antiquity addressed the planetary god Saturn with the invocation shown here. He did this in order to move the powerful divine authority so that Saturn might influence events in a beneficial way. From this invocation-prayer we can determine that in the heathen past negative aspects were not equated with the evil and demonic or pushed beyond the boundaries of the reality of life, but were considered to be facts that determined life.

“Oh master, whose name is sublime and whose power is great, supreme master; Oh master Saturn, you—cold, infertile, dark, injurious; you, whose life is serious and whose word is true; you, wise and solitary, imprenetrable; you, who keeps your promises; you, who is weak and tired; you, who more than all others is laden with worry; you, who knows neither pleasure nor joy; wise elder, well-versed in all arts; you, deceptive, wise, and rational; you, who brings prosperity as well as decline; you, who makes humans happy and sad! I implore you, oh mighty father, in your great favor and benevolent spirit, do for me this and that …”

—J

EAN

S

EZNEC

,

L

A

S

URVIVANCE DES DIEUX ANTIQUES

[T

HE

S

URVIVAL OF THE

A

NCIENT

G

ODS

], 1940

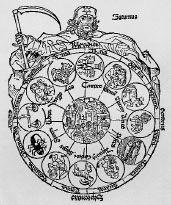

The qualities that were associated with Saturn in classical times—cold, isolation, age, petrifaction—can also be gleaned from this invocation. These traits have been derived from astrological observance since Babylonian times, which noticed that Saturn makes the longest path around the Sun of any planet. It is one of the closest planets to Earth. In the third century C.E. Saturn was equated by the Romans with the Greek Kronos, and before them the ancient Italic peoples also considered him to be a god of the fields. Kronos, the god of time, who eats his own children, bestowed Saturn with additional death-bringing qualities. Christian art has borrowed from him in corresponding images of the reaper of death or the sickle of the grim reaper. As is clear in the invocation, Saturn also unites in himself two opposing aspects. He was the god of the golden age who initiated intoxicated celebrations.

The planetary god Saturn as the ruler of the zodiac, which determines the fate of the earth. (Woodcut, c. 1499.)

In medieval treatments of the so-called “planetary children,” in which certain occupations and temperaments were placed under the domain of different planetary influences, one finds nearly all the protagonists of our book collected under the domain of the ruler Saturn. People such as hermits—in particular, Saint Anthony—along with outsiders such as witches, those stigmatized by society (such as cripples, criminals, and women in the stocks), as well as artists and field workers can be recognized in depictions of this planet’s children. Artists, geniuses, and Saint Anthony were associated with Saturn because of his temperament, which tended toward the melancholy; in Spanish

saturnino

means not only “being under the influence of Saturn,” but also “melancholy.” In 1531 in his

Occulta philosophia

Agrippa von Nettesheim added: “All who are under the influence of Saturn and can handle his

furor melancholicus

and those in whom the imagination is stronger than reason could become wonderful artists and craftsmen, for example painters or architects.”

78

Artists such as Francisco de Goya, Hans Baldung Grien, and Albrecht Dürer also use Saturn as an embodiment of age, of melancholy, or of the imagination.

The wagon of the sickle-carrying Saturn, “patron of the witches,” is drawn by dragons. The child begs for his life. (Crispin de Passe, etching, Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, late 16th century)