Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants (63 page)

Read Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants Online

Authors: Claudia Müller-Ebeling,Christian Rätsch,Ph.D. Wolf-Dieter Storl

Coca and Cocaine

After the establishment of the drug laws, coca plants (all species and varieties

6

) and the alkaloids found in them (cocaine, ecgonin) were made illegal, and to use them became punishable.

In the year 1630 on all church doors of the Peruvian kingdom an edict against astrologers, stargazers, and witches was hung. In it the witches

7

were accused of using “certain drinks, herbs, and roots, called

achuma

,

chamico

and coca, to numb their senses. The illusions and phantasms that take place are then reported as revelation or news” (Andritzky, 1989: 462). In those days people were already mixing up “consciousness expanding” with numbing. . . They saw their “opponent’s allies” in the psychoactive plants (Andritzky, 1987: 550).

Achuma

is the Native American name for a mescaline-containing cactus known in Ecuador and Peru as San Pedro

(Trichocereus pachanoi); chamico

is the ancient Native American name for the thorn apple

(Datura stramoniums

sp.

ferox).

The use of coca—which has a tradition of about ten thousand years—was forbidden by colonial rulers and the inquisitors:

The use of coca leaves was also a widespread tool of love magic. Doña Jana Sarabia, a young woman in Lima, knew “that when she used coca leaves to attract her lover she found the same enjoyment and sinful pleasures as when he had actual sexual relations with her.” … The use of coca leaves makes the precarious situation of the “colonial witches” before the tribunal particularly clear, that chewing coca leaves was a heathen worship of the “huacas, ” the Indian sacred shrines. In a law of 18 October 1569, Philipp II urged the priests to beware of its use for witchcraft and superstitious practices, but confirmed the use of coca as medicine and stimulant for the heavy labor of the Indios. At this time there was a debate going on whether or not to completely forbid the use of coca because it was a hindrance to Christianization and to destroy the plants because the Indians were constantly reminded of their past because of them, or whether to allow them to be used on account of their quality as a food supplement. In addition to its widespread use as a medicine, the defenders added that the Indian mine workers refused to work when they didn’t get their daily coca ration (Andritzky, 1987: 554).

“What did the women do before there was coca-cola culture? What was there before the masculine medicine, before the masculine science, before the masculine religion?”

—J

UDITH

J

ANNBERG,

ICH BIN EINE

H

EXE

[I AM A WITCH], 1983

In other words, when coca assists in the exploitation of the Indians, they are allowed to use it. (Strangely, coca is not allowed for Western workaholics.) Thus a number of “witches” and “warlocks” were accused because of their use of coca in combination with invocations, and were subsequently punished by the Inquisition (Andritzky, 1987: 554f.).

In the archives of the Spanish Inquisition in Peru an Indian love potion—distorted through the European witch-crazed eyeglasses—was documented. The case files state that Francisca Arias Rodríguez “took coca leaves, wax, and a woman’s shoe in her hands. Then she would nail a scissors to the sole of the shoe, while invoking Satan, Barraba, and all the legions of demons. The invocation was closed with the following words: ‘I bind you / with my heart I break you / your blood I drink / I call you to my love / come to me and stay / bound on hands and feet” (Millones, 1996: 44).

The Andean Indians handled countless problems and illnesses successfully with coca leaves in a variety of preparations: weakness, depression, painful hemorrhoids, nose-bleeds, headaches, migraines, skin tumors, colic, stomachaches, diarrhea, itchy throat, fevers, coughs, colds, sinusitis, rheumatism, arthritis, ulcers, altitude sickness, and

The Nutritional Value of Coca Leaves

8

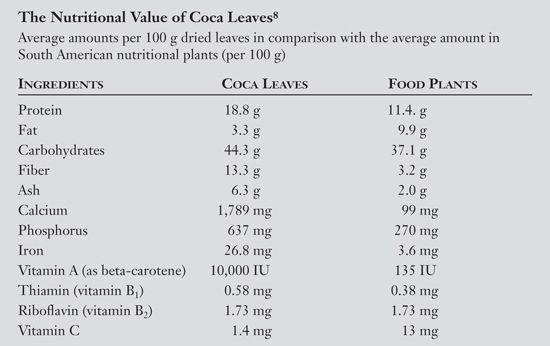

Average amounts per 100 g dried leaves in comparison with the average amount in South American nutritional plants (per 100 g) diabetes. Coca is therefore often called “aspirin of the Andes” (although it works better than the salicylic acid preparation). Native Americans regard coca as a food; indeed, the leaves have very high nutritional value (see box on page 202).

Poppy and Opium

The opium poppy (

Papaver somniferum

L. or

P. setigerum

L.), the Oriental poppy

(Papaver orientale

L. or

P. bracteatum),

and the opium obtained from these plants, as well as the alkaloids found in them, have been forbidden by the drug laws, but doctors are still allowed to prescribe them (Körner, 1994: 164).

As early as the sixth century B.C.E. among the pre-Roman cultures in Daunia, Italy, the opium poppy enjoyed respect as the “tree of life” and a sacred plant (Leone, 1995). The poppy was

thes

acred plant of the great goddess Deo or Demeter (Kerényi, 1976 and 1991).

Opium is the best and most important pain remedy humans have ever discovered in nature. It was the only reliable narcotic for centuries or even millennia (Kuhlen, 1983). Opium has also been a beloved aphrodisiac and intoxicant since the Stone Age (Höfler, 1990: 92f.).

Although the poppy was considered a witches’ plant, and despite the fact that both the poppy and opium are attributed as ingredients in witches’ salves, the Inquisition could not put a stop to their use: it was too widespread. Opium was first forbidden during a period when synthetic opiates were taking over the market. So who benefits from the prohibition? Those who make money from it!

9

“The light appeared in the darkness, and the darkness didn’t know it.”

—R

OBERT

A

NTON

W

ILSON,

M

ASKEN DER

I

LLUMINATEN

[M

ASKS OF THE

I

LLUMINATES

] (1983)

Mescaline and Psilocybin: The Forbidden Souls of the Gods

“Shall I perhaps persuade the men not to taste of the sweetest apple that the garden of our earthly paradise can produce?”

—G

IORDANO

B

RUNO (1585) IN

ON THE HEROIC PASSIONS,

1995

The peyote cactus (

Lophophora williamsii

[Lem. ex S. –D.] Coult., syn.

Anhalonium lewinii

Henn.) and the San Pedro Cactus (

Trichorcereus pachanoi

Britt. et Rose, syn.

Echinopsis pachanoi

[Br. et R.] Friedr. et G.D. Rowl.) are not expressly forbidden in the drug laws; however, their “soul,” mescaline, is (Körner, 1994: 164).

The peyote cactus has been used by Native Americans and worshipped as a god since prehistoric times. Archaeological finds from the Pecos region of Texas pay witness to the fact that peyote was used as a ritual plant for more than seven thousand years (Boyd and Dering, 1996).

When the first Europeans started to crowd into the New World they encountered shamans, which they disparagingly referred to as witches,

10

sorcerers, or black magicians. Their gods or helping spirits were disparaged as idols and devil’s workmanship; their sacred plants and drinks were defamed as witches’ brews. In a letter of the Mexican Inquisition by Don Pedro Nabarre de Isla (enacted on June 29, 1620) it says:

What the introduction of the use of the herb or plant called peyote … for discovering thieves, foretelling other occurrences, and prophesying future events, has thus to do with superstition is to be condemned, for it is directed against the purity and perfection of our holy Catholic faith. That is certain, for neither this nor any other plant can possess the power or the intrinsic property of being able to bring forth the claimed effects, nor can they cause the mental images, fantasies, or hallucinations on which the divinations mentioned are based. In the latter the influences and interference of the devil are clearly recognizable, the true source of this vice, who first makes use of the Indians’ natural gullibility and tendency toward idolatry, and then afflicts others who do not fear God enough and who did not possess enough faith.

11

The Spanish missionary Hernando Ruiz de Alarcon left behind the most detailed reports of the late colonial times about the Native Americans’ use of psychoactive magical plants—such as ololiuqui (

Turbina corymbosa

[L.] Raf.)

,

peyote, and picietl (

Nicotiana rustica

L.). His writings were published in 1629 under the title

Treatise on the Heathen Superstitions that today live among the Indians Native to this New Spain

. This work became a kind of

Malleus Maleficarum,

the legal foundation for witch persecution in the New World. In this text the following is said about the use of peyote.

Finally, whether it is the doctor himself or another person in his place, in order to drink this [ololiuqui] seed or one named peyote, which is another small root and to which they demonstrate the same trust as to the former, they close themselves in a room, which is normally a prayer room. No one is allowed to enter during the entire time of the questioning, which lasts as long as the questioner is not in his senses, for that is the amount of time in which, as they believe, will ololiuqui or peyote reveal that which was desired. As soon as the intoxication or the withdrawal of the power of judgement is over, the afflicted tells two thousand lies, among which the devil has usually strewn a few truths, so that he has completely confused or deceived them. … They also use the drink in order to find things that were lost [or] misplaced and to find out who took them or who stole them. … It should be precisely observed how much these poor people hide their superstitious beliefs in ololiuqui and peyote from us, and the reason for this is, as they admit, that he who questions them ordered them not to reveal it to us (Ruiz de Alarcon I: 6).

The prohibitionists of today would make a similar argument. But the question arises: Who is subservient to the “deception of the devil”?

Just as the use of peyote in Mexico was persecuted by the Inquisition, in Peru the medicinal and ritual use of the achuma, guachumar, or San Pedro cactus, which also contains mescaline, was forbidden and punished.

[Circa 1730, in Cajamarca] two witches were discovered on a mountain. They had spread a colorful cloth out on the earth in front, on which they had placed mollusks, jugs, and various herbs, tobacco, and a number of small stones. Between the mollusks were two jugs, one on the fire with an herb which they call

guachumar,

the other empty … [The accused testified that] the stone with a hole in the middle was called San Pedro, and that he brings it to the sick in order to purify them [and that he] because of his idol worship took care to pray to Our Father, the Ave Maria and the Creed and in the middle of his tools he placed the image of the crucified Christ and later gripped the rattle, in order to dance and to sing in his language. [Then he said] that he constantly spoke with demons who appeared to him in the form of a man with a colorful dress, but that he sometimes did not appear although he called to him, which was a sign that he was not allowed to find the lost thing again (Andritzky, 1987: 558).

“The Indian Incubus: We can read in the ‘Histories of the Occidental Islands’ that the native people take it for certain that their god Concoro sleeps with their women; for the gods in this land are nothing more than the devil.”

—J

OHANNES

P

RAETORIUS,

B

LOCKSBERG

V

ERRICHTUNG

[T

HE

P

ERFORMANCE AT

B

LOCKS

M

OUNTAIN

], 1668

Despite colonial rule, the Inquisition, and state persecution these rituals

(mesas)

in northern Peru have been retained and today are an important element in the health of the people.

In ancient Mexico the magic mushroom (

Psilocybes

pp.) played a role similar to that of the peyote cactus. The mushrooms were ritually ingested in order to receive religious visions, to enter into contact with the gods, to bestow shamanic healing power, and to prophesy. The Indians were able to keep the use of the sacred mushroom secret through the colonial period and the Inquisition. The traditional use of the mushrooms was first discovered in the middle of the twentieth century by the Wassons (Wasson, 1986). The active components of the Mexican magic mushroom were first isolated by Albert Hofmann, the man who discovered LSD. At first the active ingredients were used—just like LSD—as an aid in psychotherapy (Ott, 1996). Today they are forbidden by the drug laws.