Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants (60 page)

Read Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants Online

Authors: Claudia Müller-Ebeling,Christian Rätsch,Ph.D. Wolf-Dieter Storl

Let us recall the witch allegory of Dürer once again (see illustration page 176). This provides us with another reference to pre-Christian pagan times that explains why Aphrodite was transformed into an old woman by medieval Christians. Namely, Dürer, influenced by the humanist, astrological explanation of Saturn, interpreted the planetary position of the god in the allegory. It is in the god’s honor that Saturnalia is celebrated in Rome around the time of the winter solstice. This festival makes it possible to annul strictly defined societal order and hierarchies in permissible ways. During this period in December slaves could dance on the heads of their masters, women had a say, and subordinates could mock their rulers without punishment. It was a truly upside-down world, and this tradition continued into the modern era in boisterous carnivals in the northern regions of Europe. However, religious sects fought this celebration with lectures on morality; later, educated secular theorists—like Sebastian Brandt in

Narrenschiff

[Ship of Fools]—contested it.

Allegories of the “world turned upside down” found a wide range of opportunity in the art of the fifteenth century; one might think of pictures by Pieter Brueghel the elder, for example. The witch allegory by Dürer has been interpreted as the “allegory of the upside-down world,” a title that offers a key to interpreting this unusual engraving.

79

The witch appears as a “planetary child” of Saturn—as a person who, like hermits, artists, and the crippled, stands mainly under the influence of this planetary god of time and age. In this context the goddess Venus would be an embodiment of the astrological sign of Capricorn, which is ruled by Saturn. To depict the witch as a planetary child of Saturn and to show Venus as an old witch is explained less by way of the symbols of antiquity and more from a humanist standpoint, which often interprets antiquity from a Christian perspective.

In light of this classification it seems logical that Saturn, with his astrological symbol of the goat, became “patron saint” of witches. At the end of the sixteenth century Crispin de Passe depicted Saturn (based on Martin de Vos) as a hunched, if muscular, old man. He swings a sickle and his wagon is pulled by dragons—animals that are associated with him.

Because the believed influence of the stars and planets on the meteorological and political events in the years preceding, during, and directly following Dürer’s life were seen as wholly negative by his contemporaries, a Dürer image such as this one depicting a witch riding in a rage is totally explicable. The prevailing belief in these kinds of influences and their unwholesome nature are corroborated by contemporaries of Dürer. In 1470 the noted Kartäus monk and reform theologian Werner Rolevink from Cologne (1425–1502) published in a chronicle that in the year 1472 Halley’s comet would cast a shadow over the world, after which would follow “wars and plagues in different countries.” Johannes de Undagine, called Rosenbach (c. 1467–1537), was a clergyman and astrologist who worked in the Frankfurt region. He was in contact with Matthias Grünewald as well as with Otto Brunfels, the clergyman and botanist. In 1522 Rosenbach’s portrait was drawn by Dürer’s student Hans Baldung for a woodcut.

Plants of Saturn

80

| Belladonna | Atropa belladonna L. |

| Black hellebore | Helleborus niger L. |

| Black nightshade | Solanum nigrum L. |

| Celandine | Chelidonium majus L. |

| Celery | Apium graveolens L. |

| Cinquefoil | Potentilla erecta (L.) Raeusch. |

| Coffee | Coffea arabica L. |

| Cypress | Cupressus sempervirens L. |

| Elm | Ulmus glabra Huds. (Ill. 11) |

| Enchanter’s nightshade | Circaea lutetiana L. |

| Hemp | Cannabis sativa L. |

| Henbane | Hyoscyamus niger L. |

| Juniper | Juniperus sabina L. |

| Male fern | Dryopteris filix-mas (L.) Schott |

| Mandrake | Mandragora officinarum L. |

| Monkshood | Aconitum napellus L. |

| One berry | Paris quadrifolia |

| Opium poppy | Papaver somniferum L. |

| Plantain, common | Plantago major L. |

| Poison hemlock | Conium maculatum L. |

| Rock brake fern | Polypodium vulgare L. |

| Sage | Salvia officinalis L. |

| Sassafras | Sassafras albidum (Nutt.) Nees |

| Satan’s bolete | Boletus satanas Lenz |

| Shave grass (Saturn’s food) | Equisetum arvense L. |

| Shepherd’s purse | Capsella bursa-pastoris (L.) Medik. |

| Solomon’s seal | Polygonatum multiflorum (L.) All. |

| Spruce | Picea abies (L.) Karsten |

| Tobacco | Nicotiana tabacum L. |

| Violet | Viola tricolor L. |

| Wintergreen | Gaultheria procumbens L. |

| Wolfsbane | Aconitums pp. |

| Yew | Taxus baccata L. |

Rosenbach wrote during the same year of unrest, which was influenced by the Reformation, to Dr. Zobel, the Mainz vicar from Giebelstädt. “I divined from the stars a new condition of the Church, more wars, the movement of many peoples, one regime against the other, pestilence, and many deaths. We see this already partially fulfilled, partially it is still to come.”

81

The planetary god Saturn (Kronos) as the embodiment of time, about to eat a child—following Hesiod’s description. Behind him to the left is Aquarius, the zodiac sign ruled by him. To the right is a buck, the symbol of fertility and the orgiastic Saturnalia festival, which is celebrated in Rome during the sign of Capricorn (also governed by Saturn).

All in all the time between the second half of the fifteenth century and the first half of the sixteenth—the apex of depictions of witches—was religiously and politically, to put it mildly, a thoroughly unpleasant period. This could be read in the stars, despite the fact that the divine power of the stars had been subject to serious challenge since antiquity. To protect himself against possible accusations of worshipping false powers by the Church, the astrologer would also have emphasized that the stars are the “interpreters of the divine will” and can sometimes indicate what decisions Christ has made regarding the world of humans.

According to certain attributes some plants are also placed under the influence of Saturn.

82

When woody plants show the rings of the years, they remind us of Saturn/Kronos, of the god of time. Gray and dark leaves, bark, and a woody consistency symbolize the god’s old age. Unpleasant and pungent odors, such as that of valerian root, make us think of age and decay.

Also in Saturn’s environment belong the poisonous plants, especially those with mind-altering activity. Many of the plants classified under Saturn correspond to the presumed ingredients of witches’ salves. With the help of these plants one could experience Saint Anthony’s state of altered consciousness, which approached a condition of withdrawal so severe it achieved near total sensory deprivation, causing his inner images to manifest in the form of temptations. Like other outsiders in society, Anthony was under the influence of the planetary god Saturn.

The Painters of Witches

One question remains, and remains possibly unanswerable: What could have moved artists to paint witches, and what was their personal position on this phenomenon? Did they share a secret sympathy for the subjects of their painting or did they feel their work was advancing the good cause? We will end with a look at some of the individual painters whose subject matter included the witch and see what, if any, clues to their personal position in this regard might be unearthed from their works.

Throughout the course of this text we have described a number of pictures of witches and compared them with the ever-present panels of the Virgin Mary, which were commissioned by many ecclesiastical orders and later by the nobility or bourgeoisie. But it requires a longer, more assiduous search for evidence of Mary’s nocturnal sister. Unlike the depictions of the Virgin Mary, which can be found in every collection of early Renaissance art in the world, the pictures of witches are rarer and often in collections that are not readily accessible to the general public.

The image of the witch first entered the Christian imagination in the middle of the fifteenth century; initially only a few artists dared capture the witch fully on paper, and even more rare was a witch image committed to canvas. Equally rare at that time was the witch’s presence in the genre of free art, art that springs from an artist’s personal interest. These artists raised this subject to an independent category of pictures not embedded in an illustrative or mythological context. They primarily used drawing as their medium, only rarely making prints, and in just one instance—by Hans Baldung Grien—was the witch depicted in a “salon-quality” oil painting. Drawings are not made on commission from outside sources; in drawings artists have the possibility of putting to paper their own ideas of motifs and themes that are of personal interest. Therefore such pictures can be used to gain a glimpse behind the curtain at what personally moves an artist and how he interprets these subjects of interest.

Depictions of witches are found in three artistic contexts but rarely in the domain of the self-chosen subject. More often—predominantly in the sixteenth century—these depictions are in the context of commissions from well-to-do circles or are in the realm of the applied arts, including illustrated books.

The drawings of Baldung belong in the first category of artworks done for the artist’s personal interest. The second category of commissioned pieces is represented by such works as the cabinet picture

Hexenküchen

(Witches’ Kitchen) by Frans Francken the younger, who satisfied the desires of his client by making different variations in this romantic “shocking” genre. Also in this category are countless other Flemish and Dutch painters, who embellished the themes of “Vorbereitung der Hexen zum Flug” (The Witches Prepare for Flying) and the “Hexensabbat” (Witches’ Sabbat). These commissioned works reveal information about the tastes of the time and about the secret desires of the bourgeoisie for forbidden things. There are also many pictures of the temptations of Saint Anthony that should be included in this category, beginning with those of Hieronymus Bosch, who around 1470 was the first to make detailed renderings of heretical nonbeings enriched with images of witches (although it has seldom been established for whose commission Bosch’s panels were created). One encounters witches in the third category concerning the realm of the applied arts, where artists place their talents in the service of publishers who surround their moral and theological texts with powerful images. Included in this category are, for example, illustrations for a 1575 pamphlet by Ulrich Molitor called

Von Hexen und Unholden

[Of Witches and Monsters] and the

Compendium Maleficarum

by Francesco Maria Guazzo (1626), in which the authors created a demagogic atmosphere against the witches.

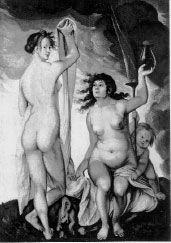

The two weather-witches present themselves to the viewer with self-assurance. Baldung’s picture oscillates between a connection to the classical archetype of Venus Kallipygos, Venus “with the pretty posterior,” and the Christian allegory of lust and sin, which is illustrated by the presence of the billy goat. (Hans Baldung Grien,

Zwei Wetterhexen

, oil painting, Frankfurt, Städel, 1523.)