Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants (47 page)

Read Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants Online

Authors: Claudia Müller-Ebeling,Christian Rätsch,Ph.D. Wolf-Dieter Storl

Albrecht Altdorfer (c. 1480–1538), one of the most important representatives of the Donau school, placed his witches in a dramatic wooded landscape such as the one in the drawing at right from the beginning of the sixteenth century.

14

Only one of the women depicted in this early drawing by Altdorfer wears the clothing of the time; the others are sparsely covered in scarves. With exalted expressions they seem to be influencing the boiling thunderclouds, which are being led to the sky by four witches riding on goats.

In the middle of the forest the witches surrender to the inebriating side of nature with ecstatic gestures and bared bodies during the witches’ sabbat. (Albrecht Altdorfer,

Hexensabbat,

white-highlighted pen-and-ink drawing, Paris, Louvre, Cabinet des Dessins, 1506.)

Hans Baldung Grien (1484–1545), who more than any other artist made the witch the protagonist of various drawings and even painted an oil on the theme, also depicted a dramatic and unleashed nature where the clouds race across the sky, lichen-hung trees are whipped by the wind, and steam rises like explosions from cauldrons or pots. Like Hans Weiditz, Hans Baldung, a painter from the Upper Rhine region who since his youthful entrance into the painting studio Grien had been called “the younger,” was also a student of Albrecht Dürer and was acquainted with the Strasbourg botanist and preacher Otto Brunfels.

15

Witches are the embodiment of nature. With their steaming bodies and long flowing hair, which Baldung has depicted like electrical streams of energy, the women arouse the forces of nature and liberate themselves from earth’s gravity during the witches’ sabbat. They were not bound to human form and were able to transform themselves into animals, usually cats, which the reading cat in the lower half of the picture suggests. (

Hexensabbat

, copy from Hans Baldung Grien, pen and ink, Strasbourg, Musée de l’ Oeuvre Notre Dame, c. 1515.)

In Baldung’s earliest chiaroscuro from 1510 (see color plates)—one of the first examples of this subject matter and the technique of connecting dramatic light and dark shades with the picture’s content—three naked witches crouch on the floor around a lidded pot decorated with perplexing symbols. A fourth rides backward through the air, sitting on a goat. She uses a pitchfork to transport a jug that has bones jutting out of it. In the clouds above left are two more witches who are being carried away by the storm, and another witch participates behind the central group of women. Bones and skulls lie on the ground along with a tassel and a hat, which is known to have been the headgear of the pilgrim monks.

16

A cat with its back to us and a hidden billy goat accompany the event.

The scenery in this chiaroscuro is determined predominantly by its nocturnal nature and atmospheric suggestions, as well as by the mimicry and dramatic expressions of the two young witches. The old witch, who while conjuring throws a plate into the air on which an animal-like cadaver is faintly recognizable, contributes to the dramatic atmosphere. Perhaps the animal lost its life in the cauldron. An inexplicable steam seethes from the cauldron despite the fact that a lid covers it and there is no fire beneath. The steam clouds that give dynamism to the picture emanate from the witches, who seem to be melded together as if by centrifugal force, their arms raised and legs stretched out.

In later drawings by Hans Baldung the plump bodies of the women, whose unified energies cause the atmosphere to surge, dominate the picture. In a copy of a drawing by Baldung dated 1515 and owned by the Strasbourg Musée de L’Oeuvre Notre Dame, the women themselves clearly create the dramatic thunderclouds with their body steam and unruly hair. Using magical formulas Baldung’s witches handle rose garlands, as a perverted symbol of their normal role in Mary iconography, with pitchforks reminiscent of Neptune’s (or Shiva’s) trident. Usually an old witch assists a younger one in anointing her body, or the elder helps the youth escape gravity. Cats howl or peek out from the edges, and remains such as arm bones and skulls let the viewer guess what the disgusting ingredients of the potion, which is usually located in the center of the activities, might be.

Images such as these are the polar opposite of the serene and stately settings painters chose for depictions of the Virgin Mary. The wild and chaotic images of the witches created by painters in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries would later assist in inspiring the fear that drove the witch hunts, a central feature of European life following the Reformation.

Because woman is closer to nature than man due to her physical cycles and her ability to create life, the reasons why Eve—the seducer of Adam—and her daughters became characterized over history as conflicting, ambivalent, disease-bringing, and opaque become obvious. The development of this negative projection is mirrored in the way the meaning of the words

hag

and

Hexe

(witch) have changed over time—both words can be traced back to

hae,

which means “hedgerow” or “grove.” At one time

hag

and

Hexe

simply meant “lady of the hedge” or “lady of the grove.”

17

But the wilderness will always grow over cultivated gardens—the witch will always threaten the realm of Mary. Thus, from a monotheistic or Christian perspective, the activities of the lady of the hedge could be understood only as destructive. This cultural underpinning informed the editor of Jacob Grimm’s 1877 edition of the German dictionary when he decided that the definition of a witch was “she who destroys the crops, fields, and soil.”

The devil is held responsible for the existence of all plants that the educated believe belong in the hedgerow. These include not only the so-called weeds, but also the plants that have the ability to alter consciousness. In the foreground of this painting, called

The Devil Sows Weeds,

the devil has even planted mushrooms in the fields. (By Jacob de Gehyn II [1565–1629],

Der Teufel sät Unkraut

, 1603.)

Plant Classification in the Visual Arts

| MARY (Cultivated plant) | WITCH (Wild plant) |

| lily | thistle |

| rose | henbane |

| strawberry | nettle |

| lily of the valley | mandrake |

| primrose | belladonna |

A biblical passage from Matthew underscores the opposition between the good and cultivated plant world and the wild and untamed one:

But while every one was asleep his enemy came, sowed darnel [weeds] among the wheat, and made off. … The sower of the good seed is the Son of Man. The field is the world; the good seed stands for the children of the Kingdom, the darnel for the children of the evil one. The enemy who sowed the darnel is the devil. The harvest is the end of time. … As the darnel, then, is gathered up and burnt, so at the end of time the Son of Man will send out his angels (Matthew 13: 25–40).

Thus the witch became identified as the “weed between the wheat,” so to speak.

The witches and the devil stand in alliance in the untamed world. The majority of art devoted to the image of the witch depicts her as the devil’s henchman more frequently than her masculine colleague, the warlock, is depicted as such. According to concepts borne in the early Renaissance, women were more often visited by the devil than men because women—as Hermann Wilcken, who was elected rector of Heidelberg University in 1569, believed—were more easygoing, forward, and vindictive than men. Women’s talkativeness also contributed, for it helped quickly disseminate the devil’s information; for this reason the devil was more likely to teach women his black arts than men. And women were associated more with the idea of seduction, which men, in their fear of impotence and physical inadequacies, have always confronted in a rather apprehensive manner. As far back as the fifteenth century the authors of the disastrous

Hexenhammer

[

Malleus Malificarum,

or Hammer of the Witches]

b

had written that the heresies of witches must be addressed, yet those of warlocks, whose numbers were said to have diminished, were not as important.

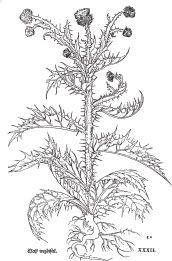

The plumeless thistle (

Carduus acanthoides

L.) is one of the few identifiable plants found on images of witches from the early modern era. A decoction of the roots was drunk as a remedy for poison. (Woodcut from Fuchs,

New Kreüterbuch,

1543.)

While the time of the Renaissance and Reformation brought about great cultural advances, it was also a time in which traditionally more tolerant attitudes toward witchcraft changed drastically. Following the devastation of the Black Plague in the fourteenth century, Catholics and Protestants alike became convinced of the existence of malign conspiracies seeking to destroy the Christian realms through magic and poison, both areas in which the witch was alleged to be proficient. The insecurity caused by the rapid changes in European culture found a ready target in the demonized figure of the witch, and thousands of women were persecuted even into the eighteenth century.

During the witch trials women were repeatedly accused of assaults on the physical and spiritual health of others in the community, on the cultivated plants, and on neighbors’ domestic animals. But the first offense the Church accused people of was hanging on to their heathen practices and leaving the path of the true believers in order to bring destruction to society. The 1484 papist bull

Summis desiderantes affectibus

[Desiring with the greatest anxiety] by Pope Innocent VIII, whose name is nothing if not ironic, fanned the flames of fear and hate against warlocks and witches. This papist bull accused “many persons of both sexes” of activities that directly threatened the rest of the citizenry as they struggled to maintain their farms and homes by cultivating nature in order to survive. In it he said: