Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants (22 page)

Read Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants Online

Authors: Claudia Müller-Ebeling,Christian Rätsch,Ph.D. Wolf-Dieter Storl

I’ll teach you lore for helping women in labor, runes to release the child; write them on your palms and grasp her wrists invoking the disir’s aid.

—

FROM

T

HE

L

AY OF

S

IGRDRIFA

The wise woman placed a bundle of mugwort in the pregnant woman’s left hand, because the guardian of mothers, Frau Holle or Artemis, is present in this aromatic woman’s herb. In addition, she burned soothing herbs and herbs that fended off evil influences in the room and the storage rooms. Mugwort and Saint John’s wort were included in this incense.

If the baby lay wrong and a breech birth threatened, the wise woman pushed and massaged the abdomen of the mother until the baby lay right. This method was favored by nearly all primitive peoples.

Although the midwife took care of the important practical aspects, she was also in an ecstatic state: She offered herself as a soul-guide to the baby, which found itself on the threshold of the earthly world. She talked with it, gave it courage, took it by the hand (so to speak), and guided it, while the contractions carried it through the birth canal. In South Africa the midwives often smoked hemp, which eased their way into the transsensory realms.

For many modern women birth is a traumatic experience that requires anesthesia and manipulation by an elaborate medical apparatus—an apparatus that, however unintentionally, causes stress and fear. Often the mothers are not even conscious of the birth of their child. In the so-called primitive societies, on the other hand, birth is an experience of the greatest ecstasy. The woman giving birth does not fight against the pain but rather—under the guidance of a wise woman—gives in to the labor and transcends her mortal ego. She is no longer in the everyday world but is “beyond the hedgerow.” In this way the midwife reveals herself as the Goddess. Indeed, the woman giving birth has become divine herself, bound to the most profound instincts, bound to the feminine archetype. Groaning, panting, sweating, leisurely moving her weight from one leg to the other, she dances the birth dance of wild Artemis until the contractions begin.

We hear over and over that for the primitives—

primitive

actually means “close to the origins”—birth is swift, uncomplicated, and nearly painless. The ease with which Native American women brought their children into the world amazed white researchers. “It has often been reported to me that the pregnant squaw simply goes somewhere remote, delivers the baby by herself, washes the child in the stream, and walks again afterwards. They do not stay in bed for a whole month (like civilized women do), but make no more out of pregnancy and birth than a cow does” (Stiles, 1761: 149).

Missionaries and Christian zealots were not so certain that the devil did not have a hand in the easy births of these “godless” savage women. Did God himself in the sacred texts not personally damn Eve, the sinful mother of man, in Eden before he banished her, saying, “I prepare much difficulty for you as soon as you are pregnant. You will bear children with pain” (Genesis, 3:16).

Herbs that the midwife uses if the labor takes too long or other complications arise grow everywhere. Native Americans have passed down many. Katawba women drank decoctions of the bark of the poplar, cherry, and Cornelian cherry bark. The Cheyenne women drank bitterroot tea

(Lewisia rediviva),

which a respected old woman whose life had not been plagued by bad luck had gathered. To shed the placenta the Navajo and Hopi drank a tea made from broomweed

(Getierezia sarothra)

and the Cherokee drank skullcap

(Scutellaria laterifolia)

(Vogel, 1982: 234). Examples such as these could fill entire books.

European midwives also had a masterful knowledge of the plants—above all mugwort—that encourage birth, relieve cramps of the perineum (with a compress made of cramp bark,

Viburnum opulis

), and minimize blood loss (for instance, ergot,

Claviceps purpurea,

which is administered in precise doses beginning with the third set of contractions). The Inquisition, during which almost all midwives were sacrificed, and the Enlightenment, which made a clinical illness out of birth and thus it had to be entrusted to a doctor, nearly destroyed this native gynecological tradition. Complicated and fatal births became problematic only after the ancient traditions had been eradicated.

The

Hebe-Ahnin

and the Men’s Childbed

The father was included in the birth even if he was not immediately present. He also found himself in an unusual state of consciousness and often lay on the ground with no energy—like the Amazonian Indian, who lay for days in his hammock, completely exhausted, while the mother was already up and walking around. This postpartum exhaustion of the man is defined by ethnologists as the

couvade,

or “men’s childbirth bed,” and is considered “sympathetic magic.” Radical feminists talk of the “sign of the beginning of the rights of the father.” In reality, however, the man was exhausted because he had sent the woman and the child as much power, as much etheric energy—

orenda,

or whatever one wishes to call it—as they required. During the Middle Ages, the Christian man prayed fervently during labor; today’s father numbs himself with alcohol and chain-smoking.

Among the Germanic peoples a ritual took place following the birth in which the midwife was the priestess. As mediator (

midwife

means “mediating woman”) between the world beyond and this world, the midwife laid the newborn on the straw-covered earth. Thus she consecrated it to the Earth Mother, to Frau Holle, who is our mother as well. She circled the child three times and inspected it. If it was healthy and viable, she lifted it up—that is where the German word for midwife,

Hebamme

(from Old High German

Hevanna

=

Hebe-Ahnin

),

b

comes from. As she was the embodiment of the goddess of fate and the ancestors, she prophesied the child’s destiny and welcomed it with a blessing. She sprinkled water, the life element, on the baby or bathed the child in it. Then she put the baby on the father’s lap. He called the child by its proper name. Usually he had dreamt or “heard” the name—humans bring their names with them; they are not named unintentionally. Often it is the name he had before reincarnation, as in the case of the great-grandfather or the great-grandmother that is being set on the father’s lap as a newborn. The wisdom of the language betrays this:

Enkel,

the German word for grandchild, means “little ancestor.”

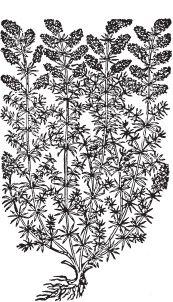

Our Lady’s bedstraw (

Galium verum

L.) is related to woodruff. In folk medicine the herb is used for kidney problems of all kinds and as an alterative. (Woodcut from Tabernaemontanus,

Neu vollkommen Kräuter-Buch,

1731.)

The ritual of the lifting up and name-giving makes the new arrival part of the living community, which it had left a long time ago, again. Weak, inviable, or crippled children were not lifted up; they were sent back behind the fence and set out (Hasenfratz, 1992: 65). However, after the ritual it was considered murder to neglect the infant.

Midwives continued to practice these “heathen” birthing customs, even while veiling them as Christian, into the Middle Ages. They collected birthing herbs and performed the first ritual handling of the child, bathing the newborn with magically powerful ingredients—an extension of the water baptism—and blessing them. They cut off a lock of the child’s hair and threw it to the demons as a sacrifice. This satisfied the monsters, and the demons left the child in peace. The midwives were also valued as bringers of children, for they knew about fertility magic.

All of this pushed the midwives dangerously close to the vicinity of the witches. The clergy and the congregation took a stand against them, among them a Dominican in Breslau in 1494 who accused these women of working with thousands of demons. It was the devil who led the midwives to recite superstitious blessings and other deceptions, according to the Augsburg midwife laws (Bächtold-Stäubli, 1987: vol. 3, 1590). Medicinal law and Church prohibitions determined that a priest must be present at birth to prevent the midwife from practicing superstitious customs. Prayers for bearing down were to replace blessings, and baths and water blessings, which mocked the holy baptism, were to be discontinued.

Bedstraw and Bewitching Herbs

During and after the delivery the mother and child are in particular need of the healing energy of vegetation; thus, they are bedded on scented pillows. The gods and heroes have demonstrated this as well. Ishtar, the Babylonian goddess of love, laid the tiny Tammuz on sheaves of grain. And it is said that in the crèche Mary laid aromatic herbs that had been left over by the oxen and the donkey. Alternatively, the Germanic peoples used the nine sacred plants that were dedicated to Freya to bed down the mother and the infant. When the missionaries of the Gospel converted the heathen lands, these important herbs of Freya quickly became “Our Lady’s bedstraw.”

Which herbs were used as bedstraw? Traditionally the golden yellow, honey-scented inflorescences of the true yellow bedstraw

(Galium verum)

were used. An English legend holds that this herb once had an inconspicuous white flower but, when the Christ child was laid upon it, it transformed into a radiant sunny gold. It comes as no surprise that the midwives not only placed it in the childbirth bed but also bathed the children in a decoction of the herb when they suffered from cramps and convulsions caused by an “evil eye.” In an old recipe book we discovered that a soothing drink was prepared from bedstraw to lessen the pains after birthing.

Common thyme

(Thymus vulgaris),

the aromatic and calming culinary spice that is still reputed by dowsers to eliminate harmful geomagnetic fields, was always included in the mix. The volatile oil (thymol) in the leaves of this Mint family plant is disinfectant and nervine. The Greeks consecrated it to Aphrodite, the goddess of love. Dioscorides prescribed it along with other herbs to stimulate menstruation, birth, and afterbirth.

In general, thyme is considered protective against evil influences. A saga tells of a girl who fell in love with a good-looking foreign traveler. The mother, who did not trust the black-eyed stranger, discovered that her young daughter had arranged to leave with him in the middle of the night. The worried mother fetched thyme and a fern called

Widritat

(from

Wider der Tat

, or “against the deed”) and sewed it into the girl’s dress. At night, when the stranger came to get the girl, he hesitated and, before dissolving into a cloud of fire and sulfurous fumes, he screeched in a devilish voice:

Thyme and fern

Have kept me from my bride!

No less of an antidemonic action is found in the yellow toadflax or flaxweed

(Linaria vulgaris).

The yellow-flowered plant in the Figwort family is supposedly loved by toads—symbols of the womb—and avoided by flies. Like flax, yellow toadflax, which grew as a weed in the flax fields, was considered a woman’s plant and was sacred to Freya for the Germanic peoples. Among other uses, it was added to a sitz bath as a remedy for discharge.

Oregano

(Origanum vulgare)

also protects the woman and the child after birth. The Greeks consecrated this aromatic herb to Aphrodite as well. The red, lightning-deflecting rose bay

(Epilobium angustifolium),

called

Froweblüemli

(“ladies’ little flower”) in Aargau, was also one of the bedstraws, like chamomile, woodruff, sweet clover, ground ivy, and wood betony

(Stachys betonica).

Sweetgrass,

Hierochloe odorata,

which smells like woodruff and was known by the Native Americans, was not to be left out. The Native Americans, who burn sweetgrass at all ceremonies, say that it has less to do with protection than with attracting good energy. To the Germanic peoples the aroma embodied gracious Freya.

Bedstraw herbs were used to strengthen the sick and invalids, to comfort the dying, to encourage relaxation, and to stimulate joyous love.

Most of the bedstraw herbs that belong in the medicinal herb bundle are the ones the women gathered on the days between midsummer and the dog days of August. They are herbs with pleasing, antiseptic volatile oils or—as with woodruff, the Mint family, and sweet clover—with coumarins, which release a pleasant and soothing haylike aroma when they are dried.

Many herbs were used by midwives as bewitching or conjuring herbs. Bewitching was understood as evil-tongued gossip and false friendship, behind which jealousy or maliciousness hid; it was also the secret curse on children who seemed to become sick for no reason or did not grow properly. With a nine-herb bath made from flowers that were usually yellow or purple—the colors of jaundice, the skin color that symbolizes envy—the illness was washed away and rinsed off in a stream or river.