Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants (23 page)

Read Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants Online

Authors: Claudia Müller-Ebeling,Christian Rätsch,Ph.D. Wolf-Dieter Storl

After the Birth

The midwife received eggs, flour, flax, and other utilitarian and symbolic offerings. Money was also given to her. It was once the custom to thank the fairy of the farm or village tree for the blessed birth of the child by offering it the umbilical cord or the first bathwater. In certain East African tribes the father plants the baby’s umbilical cord with a sapling behind the house. The little tree is lovingly cared for, as it is forever bound to the recent arrival. Christian Rätsch reports that among the Lacadonians in the Chiapas jungle the father plants the dried umbilical cord near the house with some kernels of corn. “When the corn is ripe, then he takes the ears and hangs it near the place where his wife and child sleep. From then on the ears protect the child from Kisin, the lord of death” (Rätsch, 1987: 36). The midwife wraps the afterbirth in leaves and places it in a hollow tree that only she knows about.

Our heathen forefathers knew similar customs. The northern Germanic peoples buried the “shirt” (placenta) of the newborn and the umbilical cord beneath a tree, or they hung it on branches as an offering to Woden’s ravens. For this purpose the trees and shrubs sacred to Freya, such as linden, wild rose, birch, and fruit trees, were used. The fruit trees would then bear a particularly great amount of fruit, and the child would grow and mature like the trees. Sometimes it was the duty of the midwife, or sometimes the father, to bury the afterbirth while silently saying or speaking aloud charms.

This custom has not yet died out in places where home births are still common. The bloodred bathwater is still poured under the rosebush “so that the child will have red cheeks.” In many places a birth tree, usually a linden, oak, pear, apple, or nut tree, is planted. The grandfather of Goethe, for instance, planted a pear tree at the birth of little Johann Wolfgang. A vegetative “double” that shares the etheric field with the human during its life is still seen in such trees today. If something happens to the human, the tree will become ill. Likewise, if the tree is harmed—no matter where he is—the human will also suffer.

Just as the wise woman “goes out” to guide the child being born to this side of the harbor, she accompanies the dying in their journey over the threshold as the mother of death, or

Leichenwäscherin

(literally, “corpse washerwoman,” the woman who tends to the dead). She usually knows in advance when someone is going to die because the dying process begins long before the afflicted has taken his last sigh. Long before anyone else, she notices when someone has been touched by the withered, cold fingers of death and must dance the dance of death. She is able to perceive death because she has gone over the threshold beyond the hedge and come back again. She has this gift by virtue of birth, through initiation, or by calling.

“Now, oh Mother, after you have fortified me with hope, you have cut my bonds and placed me on the top of the tree.”

—I

NDIAN

P

OET

R

AMPRASAD

S

EN

(1718–1775)

After the human heart stops beating and the person has taken his last breath, he slips out of his physical skin. He will take the same way back through the cosmic spheres that he descended through before his birth. But at first he is clumsy and insecure; he is like a moist, fragile, thin-skinned butterfly that has slipped out of its cocoon. He has barely become aware of the ancestral spirits, angels, or demons that have come to meet him from the other side. He is still a part of the world on this side. The traditions of all peoples report that the dead person can still see and hear what is happening around him. He requires help establishing orientation. He requires loving attention, just as does the child when it is born. He requires the care of Leichenwäscherin, who takes him in her arms, lovingly caresses his pale skin with her hand, and soothes his fears and confusion with gentle encouragement. “Look, my dear, at how beautiful I am making you! Look what a beautiful new shirt I am putting on you. We will have a lovely party for you, there will be lots to eat and drink!” The Leichenwäscherin even combs the hair and trims the nails of the dead person.

It is understandable that during the time of the Inquisition, the Leichenwäscherin, like the midwife, was in danger of being accused of being a witch or a necromantic, or of making pacts with the dead. She had to be careful to cloak her work in Christian garments. Usually she was deeply faithful anyway; she was Mary Magdalene, who lovingly cared for the corpse of the

Ecce Homo.

In many societies it was she who sang the laments.

After the passing, the family and close friends held a wake. For three days they stayed awake with the dead because the dead remained by its body for three days. During this time the dead person was still very close. He could reveal himself to those to whom he had been connected throughout his lifetime. Even when age, illness, and fatal blows marked him, he appeared in a radiant, beautiful, youthful form to those who were perceptive, for the etheric body remains unmarred, untouched by external influences.

During the three-day death watch, the dead person could still send important messages and give his blessings to those left behind. The light of the candles (the light of death), the smoke of aromatic herbs and resins, and songs and fresh flowers offered the deceased protection from negative influences during this important transitional phase, during this time of metamorphosis. In the Andes the natives played dice games during the wake

(velorio);

it was the dead who steered the dice and thus made apparent their preferences or indifference.

Flowers for the Dead

Flowers and evergreens play an important role in most festivals of the dead, for the plants are the ambassadors between the worlds—not just between the Earth’s darkness and the light of heaven or between the mineral and animal realms, but also between this side and the other. Plants have, as Goethe said, a “sensory” and a “super-sensory” dimension. They have their living bodies in the physical-material world, but as spiritual-sentient entities they also dissolve into the spiritual spheres beyond physical manifestation (Storl, 1997a: 91). Plants are ecstatic (standing outside themselves) in the truest sense of the word. What we call

spirit

or

soul

floats freely around plants in the macrocosmic nature, in the world where the ancestors and gods are also found. To speak with the plant spirits, the gods, and the ancestors, the shaman must also be able to travel outside the body and become ecstatic.

Nowhere is the soul of the plant more tangible in the incarnated world than in the flower. The soul of the plant is best revealed in its color, its scent, its delicacy, and sometimes in the measurable warmth of the flower. Because it is a sentient being, it can touch not only our souls but the souls of the deceased as well. Flowers are the road signs for the dead in the macrocosmic dimension.

The custom of bedding the dead in flowers is ancient and was first practiced more than sixty thousand years ago by the Neanderthals, who buried their dead in a cave in what is currently Iraq. Pollen analysis clearly shows that they laid their dead on beds of bushels of medicinal herbs—yarrow, centaurea, ragwort, grape hyacinth, mallow, ephedra, and others. The ground around the bed was strewn with mugwort. It is possible that mugwort was already considered a plant of Frau Holle and was consecrated to the grandmother of the Earth.

The Mexicans believed that the dead could see the color yellow in particular. For this reason they made a flower carpet out of marigolds

(Tagetes)

that stretched from the house to where the wake was taking place to the table piled high with the dead’s favorite food and with cigars,

pulque

(agave wine), fruit, and incense censers with copal (Cipolletti, 1989: 207).

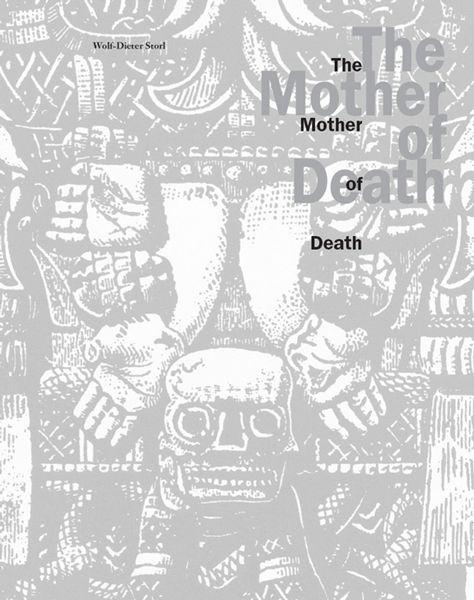

The Earth Goddess not only bestows a new life, but she also snatches away the old one. This trait of the cosmic mother of death is particularly apparent in the Aztec statue of their earth goddess, Coatlicue (Snake Mother). Her head is made from two snake heads and she wears a necklace of human hearts, hands, and a skull. Her skirt is woven from snakes.

The Festival of the Dead

The custom of having a party along with the wake is nearly universal. Feasting, copious drinking, singing, and dancing mark these celebrations. The dead are invited to celebrate, and when the festivities are over they are thanked for the fun. The celebrants “lift off”; they go, so to speak, a few steps into the spirit world. They are “spirited” or ecstatic.

Since the inception of Christianity, the Christian priests had continual problems trying to subdue this festival. The first action the synod of Litninae forbade was the “blasphemous customs at the graves of the deceased.” In the year 1231 the council of Rouen outlawed dancing in the graveyards and in church. In 1405 another council forbade musicians, actors, and jugglers to practice their crafts at the cemeteries (Raiber, 1986: 9). The Church also damned tearing out the hair, scratching the face with the fingernails, and ripping off the clothing as expressions of grief.

In countries not influenced by Christianity, where alcohol is not used to help soothe the mourning, another spirit-moving substance is often used. The Huichol shamans ingest peyote so that they can guide the dead. Iboga plays this role in Africa. But above all, hemp

(Cannabis sativa)

is the sacred herb of death ceremonies. In the

Pen T’sao

of Shen Nung, the most ancient herbal with roots dating to the Chinese Neolithic period, hemp is said to make the body light and enable the human to speak with ghosts. The Scythians, a mounted nomadic people of the West Asian steppes, reportedly placed their dead in a tent with dried hemp burning on glowing stones. The inhalation of the smoke relaxes the soul enough from the physical construct of the body, making it possible to accompany the deceased part of the way into the regions beyond. In India hemp is considered the herb of Harshanas, the god of the death ceremony

(shraddha).

Those who are left smoke ganja at the funeral pyre or eat it spiced with pepper as a delicacy. Those in mourning cut their hair and sacrifice it, as is done for a birth or other important ritual of transformation. With the help of hemp they meditate on the dissolution of the five physical shells of the body (

Pancha Kroshi).

They watch as Shiva, swinging the trident, frees the deceased from his material chains in the wild dance of the flames.

1

They see the demons and the elemental beings who dance with Shiva, and they take delight in the flow of life energy.

In Neolithic China it was the custom for participants of the festival of the dead to wrap themselves in hemp garments. The

Codex Leviticus

of the ancient Hebrews stipulates that the last clothes of the dead be made from hemp fibers. The idea could have come from Egypt, as the bandages of the mummies contain many hemp fibers, and in the mouths of the mummies archaeologists have found hemplike resin mixtures (Behr, 1995:33). Undoubtedly the hemp seeds that have been found in Germanic graves were thought of as food of the dead. Hemp was, as were all other fibrous plants, sacred to the goddess of fate, the “spinner” Freya or Frau Holle. Hemp seeds are still food for the dead among the Slavs and the Balts of eastern Europe: A hemp soup is cooked and eaten at Christmas or the Epiphany, when the dead visit their families.

Departing gifts are still given to the deceased before he is festively carried to the grave, bound to a tree in the grove of the dead, burned on the funeral pyre, or thrown into the sea from a ship of the dead. Russian women write their men farewell letters. Usually the dead person gets his favorite things. These are also “killed” by being broken or burned so that they can be used on the other side. Even medicinal salve is pressed into the dead’s hands so that he can heal himself in the realms beyond. Among the Germanic peoples the

Totenfrau

a

put good shoes on the dead person’s feet for the long walk to the realm of Frau Holle. This ancient custom has been kept alive by the cowboys, who wear their best or often new cowboy boots in their caskets.