Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants (48 page)

Read Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants Online

Authors: Claudia Müller-Ebeling,Christian Rätsch,Ph.D. Wolf-Dieter Storl

[These people] unmindful of their own salvation and deviating from the Catholic Faith, have abused themselves with devils, incubi and succubae, and by their incantations, spells, conjurations, and other accursed superstitions and horrid charms, enormities and offenses, destroy the offspring of women and the young of cattle, blast and eradicate the fruits of the earth, the grapes of the vine and the fruits of the trees; and also men and women, beasts of burden, herd beasts, as well as animals of other kinds; also vineyards, orchards, meadows, pastures, corn, wheat, and other cereals of the earth. Furthermore, these wretches … torment with pain and disease, both internal and external; they hinder men from generating and women from conceiving; whence neither husbands with their wives nor wives with their husbands can perform the conjugal act.

18

In the end the witch was more likely to be seen as offering her services as a black magician and weather-demon, as a representative of “unholy” nature who brings disease, than her masculine counterpart. Perhaps the woman witch was more strongly anthematized because of the fears she inspired of being able, like Eve, to coerce and cajole others into doing her bidding. Though not actual embodiments of the devil themselves—he was depicted as in attendence with witches at their Sabbaths—like Eve, witches emerge from the left or sinister side, traditionally viewed as the devil’s realm. Accordingly, her trance journeys, her plant knowledge, and her ability to control the weather were no longer viewed as socially beneficial, as they had been in pagan times, but as devices of the devil to seduce godfearing men from the Christian way.

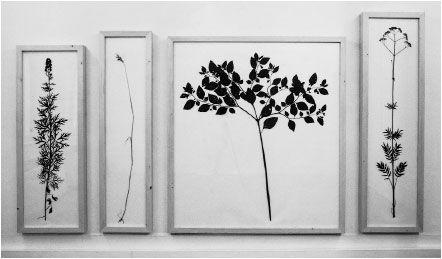

In 1985 Herman de Vries made this four-part work

monumenta lamiae

. It consists of four plants with the reputation of having once been ingredients in witches’ salves. They are (from left to right): monkshood

(Aconitum),

rye with ergot

(Claviceps),

belladonna

(Atropa),

and valerian

(Valeriana).

v (Herman de Vries,

Vierteiliges Monument aus getrockneten Pflanzen;

photo by N. Koliusis.)

The Symbolic Plants of the Witch

MANDRAKE (

Mandragoras

pp.)

During Christian times the root of this herb was called

Hexenkraut

(witches’ wort), Unhold Wurzel (monster root), or Satan’s apple. In German it is called

Alraune

. It was so treasured as a panacea that it was called

Artz-wurzel

(doctor root),

19

and quack doctors even carved fakes out of other roots and sold them for high prices. Into the sixteenth century a wise woman or a witch was called an

Alraundelberin

(mandrake bearer). Golowin (1973: 33) discusses these women and refers to various examples from the fifteenth century and onward in which women were persecuted because they used mandrake for magical purposes. Those who kept mandrake in their homes received information about the hidden connections of the present and the future. A mandrake was even found wrapped in fabric in a very small box under the nuns’ chairs in the choir at the north German cloisters at Wienhausen. The art historian Horst Appuhn explained that such forbidden possessions could be safely sacrificed in such a sacred place.

20

HENBANE (

Hyoscyamuss

pp.)

Hildegard of Bingen mentions henbane oil as an ingredient in a bath that was purported to be a remedy for leprosy. In art henbane has played only a subordinate role. For example, the plant was identified on a panel by Albrecht Altdorfer (Behling, 1957: 126f.) that depicts John the Baptist and Saint John the Evangelist. The painter placed the henbane near the lamb, the symbol of the death of Jesus, and John the Baptist prophetically points to the animal. Henbane was described by Albertus Magnus to be a plant that invokes demons, so we can interpret that the demons are driven out through Christ. Henbane only rarely appears in pictures of witches, although it is referred to repeatedly in literature as an ingredient in the witches’ brews and salves.

THISTLE (various species)

Because rainwater gathers in the leaf bases on the stems of thistles, these thorny meadow plants, of which there are three genera and numerous species, was known as the

Labrum Veneris,

or “the bath of Venus,” during antiquity. (

Labrum Veneris

can also mean “the lips of Venus.”)

Because of its prickly appearance, thistle is a symbol of negative characteristics and their attendant circumstances. Thus thistle was considered a sign of laziness, decay, or corruption, although its prickliness was also thought to guard against demons and witches. If the plant is hung in the barn, the thistle protects against black magic.

In art thistle is found now and again in pictures of witches, and it is also found (along with the goldfinch) on images of the flight to Egypt, in which the thistle symbolizes the salvation of souls.

NETTLE (various species)

Konrad of Megenberg wrote that nettles awaken lust. Thus Albrecht Altdorfer logically placed the plant in a picture of Susanna at the bath in which two lascivious men lie in wait and watch Susanna, though she was able to resist their indecent intentions. Nettle played an important role in pictures of witches because the plant represented the wilderness and weeds. The botanical name for blind nettle,

Lamium album,

is derived from the Latin word for witch, and the herb appears on the Isenheim panel by Matthias Grünewald as one of the components that were being worked into a remedy for Saint Anthony’s fire.

MONKSHOOD (

Aconitum napellus

L.)

The common name of this plant probably derives from the similarity of the flower to a monk’s hood or a knight’s helmet, as it is also called. In German its common names include

Sturmhut

(storm cap) and

Eisenhut

(iron cap). But the name of the Egyptian goddess Isis can also be found in Hieronymus Bock’s 1539 rendition of a picture called the

Isenhütlin

(Little Iron Hat). Heavenly and divine associations also become animated in the southern Austrian names

Himmelmutterschlapfen

(heavenly mother slipper) and

Venuswägelchen

(little chariot of Venus) that Marzell (1935: 80) found in nearby regions. Venus also came to mind for the French when they gazed on this poisonous blue-flowered plant, and thus they call it

char de Venus

(chariot of Venus) (Gawlik, 1994: 14).

The depiction of the Virgin Mary with the baby Jesus derives from the model of Isis with the baby Horus. In ancient Egypt and the tradition of late antiquity, Isis knew about medicinal plants. Isis cults in southern Germany were active until the conversion to Christianity. Over the course of the Christian conversion the love goddess was demonized and transformed into a witch, and monkshood was mentioned repeatedly in her flying salves. The association of the medicinal and poisonous plant monkshood with goddesses that belong to different religious realms is a long cultural tradition.

The Demonization of Nature and Sensuality

In the pictures of witches that we describe here, the elemental violence of nature is depicted. This usually includes a wilderness that has been left alone, without any cultivating or domesticating interference. Storms rage in this wilderness. Life triumphs over transitoriness, and in a countermovement transitoriness triumphs over life: The young witches’ plump bodies, in their prime, are placed in sharp contrast to the skulls and bones on the ground, while animals and, it appears, children are sacrificed in the cauldron. Among the witches themselves the old and the young do not fight. They are not as unininterested in one another as they are in other images in which naked women are grouped together, such as the three Graces, or as representatives of the different stages of life. Quite the reverse is true: The witches are bound together in a communal cult activity in an ecstatic way.

21

Old women with wrinkled skin and drooping breasts anoint the bodies of their younger colleagues, who are in the flower of their life. “Nature” is represented by the forest landscape with trees (often dead trees), and moss and lichen offer a nourishing ground. Unbridled nature is also shown in the untamed, trancelike ecstasy of the women, who, with their obscene farts, coquettish exhibitionism, and blasphemous consecration of sacred objects, reveal that there is more to their actions than a lack of modesty or good behavior.

“The first Christians slandered nature as a whole and in detail, in the past and in the future. They cursed nature in and of itself. They damned it so completely, that even in a flower they only saw evil incarnate—a demon embodied. … Not only were we [the humans] demonized—for goodness’ sake—but all of nature was demonized. If the devil is already found in a flower, then he must really be present in the dark forest.”

—J

ULES

M

ICHELET

,

L

A

S

ORCIÈRE

[T

HE

S

ORCERER

], 1952

With their ecstatic comportment and naked bodies the witches represent the unruly and intoxicating power of nature itself.

22

However, despite all the fertile lusciousness suggested in witch images, the women do not represent motherly, decent, and charitable femininity but rather the threatening, raging, destructive part of feminine nature that is repulsed not even by infanticide.

When we compare such images of witches in the wilderness with depictions of the environment surrounding the Virgin Mary, we see that in the latter the divine clearly shows itself as a spiritualized form of nature. The wooded landscape of the witch’s scene stands in contrast to the architectural landscape or the enclosed garden in which Mary sits with the baby Jesus and the saints. The naked body stands in contrast to the concealed one, as do the ecstasy and the solemn peace, the unleashing of desires and their subjugation, the wilderness and the world of cultivated plants. The divine sphere is thus understood as a perfect example of the spirit. If humans understand themselves as spiritual beings and the creation of God “in his own image,” as it says in the Bible, then the task is to distance oneself as far as possible from nature and to make one’s separation from nature as distinct as possible.

This path has been argued since the beginning of Christian culture. The more humans, through the strength of their will and their capacity to reason, shield themselves from their inner nature and the nature they encounter in plants and animals, the more those humans can, according to Christian doctrine, participate in the sphere of the spiritual and become closer to God—a masculine god, of course. The spiritual and moral duty of humans to fence themselves off from nature inevitably leads to a polarization of values: Nature is bad, spirit is good. Such a value judgment leads to the spirit becoming “divine” and nature, in contrast, becoming “diabolic.” In this context it is revealing that the medieval paintings of the heavenly spheres depict an abstract gold background (or deep blue arches), and paradise is built up like a kind of heavenly Jerusalem, while lush nature is allowed a presence only in hell. In the cultural sphere of the West (and this is the only one we are speaking about here) animals and plants were discovered very late as suitable subjects for art, and it was not until even later that they were depicted as the sole feature of a composition.

The human’s desire to distance himself from nature leads not only to a liberation of the forces of nature, which the heathens saw embodied in gods and elemental spirits and whose forces the human allegedly felt surrendered to (as authors still emphasize today), but also to distancing, to an alienation from nature—and ultimately to its destruction, which, as we know, has had devastating consequences.

Places where the untamed forces of nature manifest became, in the Christian perspective, workshops of the devil. These were predominantly the white-water rapids, mountain ponds, high ridges, deep mountain ravines, and steep cliffs. In these picturesque places nature spirits once revealed themselves to humans. The high mountains were where the Rübezahl—the mountain spirit, weather god, and herb spirit—lived, and such wild places were called “Rübezahl’s gardens” or “Rübezahl’s pulpit.” These places were later renamed “devil’s ground” or “devil’s pulpit.”

People’s enduring belief that nature beings live in cliffs where the weather has left its traces or in ancient knotty trees that the powers of imagination have turned into bizarre images and faces recently became clear to me. On a trip to the Massa Marittima in Tuscany I came to a small village called Magliona. There stands an olive tree (

Olea europaea

L.) that is called

olivo della Strega

—the “olive tree of the witches.” If one believes the families who live there, who can date the olive trees in their own garden four hundred years back, then the olivo della Strega, which is found near an old church, is nearly six hundred years old. Out of its totally hollow, knotty, enormous trunk grows a new trunk that still bears green leaves and olives. When you walk around the tree, which is fenced in as if it were a shrine to nature, the hooked-nose profile of an old woman can be seen in the twisted, overgrown bark. However, this imagistic association with the witch is not why the tree got its name. When asked why this tree is called the olive tree of the witches, an old native olive farmer explained that tree nymphs still live in such ancient trees, and over time they have become witches. Thus not only did the farmer know the philosophy of his ancestors, but also he knew something about the wondrous transformation from nymph into witch.