Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants (44 page)

Read Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants Online

Authors: Claudia Müller-Ebeling,Christian Rätsch,Ph.D. Wolf-Dieter Storl

The word sabbat … has absolutely no connection to the biblical sabbat or to the number seven, but rather it is, as Summers thought, most likely derived from Sabazios, a Phyrgia god who is often compared to Zeus or Dionysos and is considered the patron deity of orgies and obscene practices (Castiglioni, 1982: 34).

In the late Middle Ages, and particularly in the early modern era, the heathen dance cults became such a thorn in the side of the Church and the rulers that the groups were totally defamed with the help of broadsheets, papist bulls, and the

Hexenhammer

(hammer of the witches, or

Malleus Maleficarum

). The written testaments—similar to what might be found in the

National Enquirer

—manipulated popular opinion.

During the Inquisition people who were under suspicion of having taken part in “diabolic orgies” were tortured and murdered. The state, for its part, sanctioned the consumption of heathen intoxicants. In particular, the “beer purity laws” of 1516, written by the Bavarian duke Wilhelm IV, represented an attack on the heathen nature religions and witchcraft medicine (Rätsch, 1996b: 170 f.). With this ordinance, which is often misunderstood today as nutritional laws, the use of the dangerous witches’ plant henbane was forbidden.

Some early authors mention that witches’ wine was used as a sexual stimulant: “On the witches’ sabbat beer, apple wine, pear wine and water in which witches’ wort [henbane] had been soaking, brought the people to dance … but in a smooth, pleasant way, demonstrating no trace of epileptic or violent movement.” Father Sebastian Michaelis declared that the witches favored drinking a wine that had been stolen from the wine cellar in order to stimulate sexual desire. … The witches’ wine was often described as dull and with little taste (Wolf, 1994: 451).

The Sabbat on the Allmend

“In the canton of Lucerne the forbidden dance of the night took place on the Allmend. The Allmend is an area that belongs to the villagers communally and that is used by them according to a specific law. Animals are grazed there, and hemp and flax is cultivated in unfenced gardens. Different forms of love magic demanded a visit to the flowering hemp fields. This often caused states of aphrodisiac intoxication. The forbidden dance on the Allmend, and the ingestion of the consciousness-altering plants that grew there, encouraged illicit intimate relations between the youth. Nightly dancing outside the village, aphrodisiac plants, and erotic sentiment went against the dominant moral codes. The happenings outside of the village were demonized and forbidden as being witches’ sabbats” (Lussi, 1996: 115f.).

Witches’ wine has moved the soul throughout history and continues to do so today. Because wine was known to be an aphrodisiac, it was assumed to be the foundation of the love potion made by the Celtic “herb witch” Isolde, whose history can be read in the countless early and late workings of the story of Tristan and Isolde. Wine was identified as a love potion and therewith automatically belonged to the alleged repertoire of witchcraft medicine. In the opera

L’Elisir d’Amore

[The Love Potion], by the Italian composer Gabriel Donizetti, the magical drink is nothing more than red wine. Although wine was associated with the outlawed machinations of witches, it has never been—except during Prohibition in the United States—truly forbidden. To the contrary, the Church lifted the sacred use of wine from the Dionysian orgies and used it as the wine for their Mass. However, they forgot—or maybe they left them out on purpose?—to add the psychoactive ingredients of the Dionysian drink to the Mass wine. Wine is also the preferred food in cloisters, and it is one of the most beloved intoxicating drugs of the upper classes. But just as wine can have ambivalent effects, like a true pharmakon, it was always viewed with ambivalence by society and politicians.

Even champagne was considered a “satanic wine” as late as the seventeenth century! That was perhaps the inspiration for one of the most spiritually moving novels of the early German Romantic era. In 1815 E. T. A. Hoffmann—a well-known alcoholic and laudanum drinker—wrote a classic of the Gothic novel genre with the multifaceted title

The Devil’s Elixirs

. This book refers to a historical wine from the writings of Saint Anthony

127

that is supposed to be like Syracuse wine in appearance, smell, and taste. Those who taste this wine, “the wonderful drink with spiritual strength,” will have their minds strengthened and will be bestowed with the “joy of the spirit.” The aroma of the wine is said not to be “numbing, but more pleasant and benevolent”—in other words, not narcotic but stimulating and uplifting.

Hoffmann described the effects of the wine of Saint Anthony as if it were a psychedelic like LSD: “I gripped the box, the bottle, soon I had taken a powerful swallow!—Embers streamed through my veins and filled me with an incredible feeling of happiness—I drank once again and the desire for a new, beautiful life rose up in me!”

The cloister brother who could not or would not resist tasting the drink, which was kept in the reliquary, broke out of the cloister afterward, out of the stern structure of hierarchical power, and stumbled like a modern anarchist into the chaotic sensations of the world. Were it not for his conscience, had he not been caught sleeping in his own cell, and were he not bound by horrible feelings of guilt he would have had a beautiful life, free from all societal demands—Dionysian through and through. E. T. A. Hoffmann convincingly demonstrated in his novel how a Christian upbringing leads to spiritual uncertainty and schizophrenia.

Surprisingly, the witches’ wine, the former “blood of Dionysus,” can still be enjoyed these days. In Baden the late-season Burgundy red wine Hex von Dasenstein can still be found.

128

Countless modern types of German beer are named after witches and devils: Halloween Pumpkin Ale, Hexenbrau, Satan, Lucifer, and so forth. But because they all are brewed according to the purity laws, they are all legal drugs.

Wine As Medicine

Since antiquity wine has been known as an intoxicant, an aphrodisiac, a medicine, and a poison—in short, it has been known as a pharmakon. But in medicine wine serves primarily as a carrier for other ingredients.

Ananamide has been discovered in red wine. This substance is made into a neurotransmitter. Ananamide binds to the same receptors as THC, the active ingredient in hemp, and transports the person to a pleasant feeling of contentment. Ananamides are also found in chocolate and cocoa (Grotenhermen and Huppertz, 1997: 58ff.).

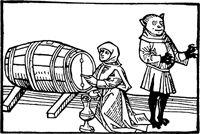

A witch taps the wine with the help of a nail while a demonic helper spirit protects her. During the early modern era wine was demonized because of its intoxicating, medicinal, and destructive properties. (Woodcut from Hans Vindler,

Buch der Tugend

, Augsburg, 1486.)

Ingredients of the “Witches’ Brew”

The three witches in Shakespeare’s

Macbeth

, who fell under the protection of Hecate, prepared a “charmed cauldron” whose ingredients are precisely listed (act 4, scene 1). In the kettle, which is surrounded by elf spirits, the first witch placed the first ingredient, a toad.

129

The second witch added more ingredients:

Fillet of a fenny snake

In the cauldron boil and bake:

Eye of newt, and toe of frog,

Wool of bat, and tongue of dog,

Adder’s fork, and blind-worm’s sting,

Lizard’s leg, and howlet’s wing.

c

The third witch had still more to offer:

Scale of dragon, tooth of wolf,

Witches’ mummy, maw and gulf

Of the ravined salt-sea shark,

Root of the hemlock, digged i’th’ dark;

Liver of blaspheming Jew,

Gall of goat, and slips of yew,

Slivered in the moon’s eclipse;

Nose of Turk, and Tartar’s lips,

Finger of birth-strangled babe,

Ditch-delivered by a drab,

Make the gruel thick and slab.

For the finale, Pavian’s blood is added. Unfortunately, Shakespeare does not reveal how the witches’ gruel is used.

In this recipe two plants are named directly: henbane

(Hyoscyamus niger)

130

and poison hemlock

(Conium maculatum, Cicuta virosa).

The other ingredients seem to be parts of animals, but these designations were probably secret or ritual names of plants. The

rat’s blood

is called “slips of yew,” and

wolf’s teeth

is a folk name for ergot (Golowin, 1973: 42). The author, who dabbled in herbalism and alchemy, probably did not write down a general recipe for the witches’ potion, but preserved for eternity a preparation of ingredients whose names were kept secret (cf. Tabor, 1970). These plants belong to the pharmacologically active ingredients of the witches’ drink.

The Image of the Witch

Books about witches overflow with illustrations and pictorial manifestations of the witch’s legendary existence. Yet even with close scrutiny it remains difficult to find any reference to witchcraft medicine in such pictures; identifiable plants are depicted all too rarely and rarer still is any evidence of the witch-women as herbalists or healers. Before the greatly obscured connection between women healers and the herbs and plants they used can be traced through culture and art history, it is essential first to visualize the image with which the witch has been branded and to seek out different aspects of the activities of the witch.

This reconnaissance mission will first lead us to the woman who is the healer of humanity, the one employed and validated by the Church; naturally, she is not the witch. Then we shall travel into the depths of a demonized nature, where the path leads to sensuousness and finally to the woman who mixes poisons and is a healer. But she left no written records to explain the practices of this tradition, and reports on witches by the Inquisition, which sought to exterminate them, while of interest, are obviously biased. How then are we to proceed with our mission?

Renaissance painters may provide the best documentation of the witch and the powers attributed to her by her contemporaries. The works of Bosch, Dürer, Grien, and other artists of the time hold significant clues for reconstructing the actual religion of the witches and its practices involved with healing, weather control, and divination. Though we cannot know if an individual painter’s inspiration was prompted by Church propaganda or a secret sympathy for the tradition, the consistent use of various elements and motifs in these works provides a valuable portrait of the spiritual tradition these women inherited from Europe’s pagan past. Furthermore, there is another special role played by pictorial works that I will examine below that makes these works particularly relevant to our mission.

A witch whose demonic helping spirit lurks in her blowing hair approaches a wounded man with gestures of invocation and healing. (Detail of a woodcut illustration from Cicero,

Officia,

Augsburg, 1531.)