Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants (15 page)

Read Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants Online

Authors: Claudia Müller-Ebeling,Christian Rätsch,Ph.D. Wolf-Dieter Storl

The Buck: The Divine Dispenser

In addition to Frau Holle, the witches were conscious of a further primordial Paleolithic deity when they looked over the hedgerow: namely, the buck, the horned companion of the Goddess, who dispenses pleasure. For the people of archaic cultures the buck, particularly the stag, embodied the divine powers of creation. The relationship is repeatedly demonstrated in the Indo-European languages: The Vedic Indians call God, the dispenser of life and creator of souls, Bhag or Bhagwan.

2

Bog

is the general Slavic word for God. The

boogeyman

was not only the “black man” who scared children but also the

Waldteufel

(wood devil), the “spring-in-the-field” who jumped on the shepherd maidens or young farm girls when they were collecting berries. The

boggard

was a well-known, unpredictable nature spirit in British folklore.

Boogie-woogie

is the strange, seductive, erotic music of black Americans, which seemed suspect and satanic to the puritanical white Americans. Böögg is still the name of a scary ghost of Alemannic lore, and

Bockert

is the traditional mask worn for Fasching (Shrove Tuesday). In the Himalayas the archaic horned god is still worshipped as Pashupati, “the lord of animals and souls.” He is identical to Shiva, the lord of the cave, the possessor of the phallus (lingam) who rides the wild steer. He wears the waxing and waning moon as horns in his long matted hair. His trident, which actually represents a World Tree (among other things), was reinterpreted as the devil’s pitchfork by the Zoroastrian priests (Storl, 2002: 142).

The Chinese remember the archaic horned god in the figure of the primordial emperor, Fu Hsi, who taught the first people how to hunt, fish, and read oracles with yarrow sticks for the I-Ching, and as Shen Nung, who was the first human to teach the people about rituals and ceremonies, herbalism, and agriculture. The Great God revealed himself as a virile steer in Southwest Asia and North Africa. In Egypt he fertilized the sky goddess Nut daily, while as Zeus he fertilized Europe in the form of a steer. The roaring stampede of the heavenly steer embodied thunder, rain, and fertility. The archaic lord of the animals also lives on in Pan, the Arcadian shepherd and hunting god. He has goat’s hooves and horns. He lustily chases the nymphs. All nature spirits dance to his flute.

The primordial God mainly appeared to the Neolithic Europeans as a stag with brilliant, radiant antlers. The stag was considered to be the sun in animal form. As the sun he fertilized the earth, the womb of the Goddess, so that vegetation would sprout and grow. His life-bringing light penetrated the deepest corners of the human heart just as it penetrated the dark ravines of the forest. With the advent of Christianity, the sun-stag was transformed into the stag of Hubert or Eustatius. Now it is the light of Christ that radiates from the antlers. Today the stag ekes out an existence on the label of a popular herbal liquor (Jägermeister), which comes in a forest green bottle.

The Celts knew the god with the stag horns as Cernunnos. He is depicted sitting cross-legged like Buddha or the proto-Shiva from pre-Aryan India. He is surrounded by forest animals and rules over all sentient beings. Like Shiva, Cernunnos holds a serpent—the symbol of wisdom and of ever-regenerating life—in his hand. The name Cernunnos comes from the Indo-European root

ker,

which means “growth” or “to become big and hard.” Thus he embodies the principles of growth, copulation, and fertilization. He was also the possessor of the phallus that impregnated the Great Goddess.

The Neolithic farmers of Europe noticed that the yearly growth cycles of the stag’s antlers—from the time they were shed in February or March to the scraping off of the velvet from the antlers in August—coincided with the stages of the growth of the grain, as well as the sowing and the harvest (Botheroyd, 1995: 160). Thus they had a tamed stag pull the wagon of the Goddess, and sometimes a tame stag pulled the plow that pushed into the earth and opened it up for the seeds, like a phallus. At harvesttime they danced a stag dance. The stag dance, a tourist favorite, is performed on September 3 at Bromley Abbey in England, during which the young boys carry a huge stag head in front of them. It is a last remnant of the Neolithic harvest festivals. Here and there, the last sheaves harvested are made into stag forms that are still called stag or harvest buck. They are triumphantly driven into the village on the harvest wagon (today they use a tractor). The roots of medicinal herbs, which are sacred to the Goddess, were in archaic Europe naturally dug with an antler, a horn that was possibly worked with gold. Gold represents the sun stag in mineral form (Storl, 1997a: 182).

In Germanic mythology aspects of the archaic god live on in Thor, the favorite god of the farmers. While hurling thunder and lightning, he drives over the land in a wagon drawn by billy goats. The goddess Freya is not resistant to him either: Occasionally she is said to take on the shape of a white goat in rut. The magical animals that are harnessed to the hammer-bearer’s wagon are identical to the black thunderclouds. They are rain bringers whose waters make the meadows and fields green and fill the barrels and vats of the farmers. The clouds that swell and rise on hot summer days are still called “storm bucks.”

There is a saga that tells how the great thunderer Thor once visited a farm with Loki. As usual, Thor was friendly to the farmer. He slaughtered his goat, skinned it, cooked it in a great kettle, and invited the whole family—husband, wife, and children—to eat it. However, he warned them to carefully collect all bones and to throw them on the goatskin when they were through. The next morning Thor swung his hammer over the skin and there stood the goat, alive again, but lame in his hind foot. The farmer’s son had split a thighbone with his knife in order to suck out the marrow. Thor’s eyes flashed with rage, and he would have killed the family immediately if their crying hadn’t made him take pity on them. As punishment he took two of the children with him, and they served him loyally from then on (Golther, 1985: 276).

Following the example of the much esteemed Thor, the heathen Germanic peoples sacrificed billy goats to the earth goddess. These animals were also visibly resurrected and transformed into corn, wheat, rye, legumes, hemp, or flax—the unhampered and dynamic growth of the agricultural bounty. And when the wind blew through the undulating cornfield it was said that “the goat is racing through the corn!” But this goat, this “vegetation demon,” also had to be sacrificed: When the mower is cutting the last row, the Swabians say, it is “cutting the goat’s neck.” In many places the last sheaves of grain are still called bucks. To thresh is to kill the buck. Often goat is served for dinner during threshing time. The horns of the sacrificed goat are hung on the door to protect the house and barn from black magic and lightning. For a long time people still believed in the protective power of Thor’s goats. A few years ago a Swiss farmer told me that he let a billy goat run free around the barn so that if the devil came into the barn, he would take possession of the goat first and leave the other animals alone.

Thor and his goats embodied cosmic sexuality in the imagistic thinking of rural farmers. But Thor’s animals could also dispense potency and health to the human root chakra: He who rubs his member with goat tallow will be favored above all other men by the women. The smoke of goat hair was used for the relief of pain in the sexual organ. And the western Slavs believed that a man who was bewitched by a woman could be freed by smearing goat blood on himself.

If we inadvertently think about the billy goat when we hear the word

buck,

it corresponds to the medieval fantasy of the animal that was nourished by a Germanic belief in Thor that later melded with the Pan myth of classical antiquity. The witch hunters believed that at the nocturnal witches’ sabbat the devil held court in living form as a lusty, stinking black billy goat. Their spies reported that the sabbat participants danced around in a circle turning to the left, with their faces outward. This is definitely correct, for all archaic round dances turn “with the sun.” Music was allegedly made with dead cats, and they drummed on the heads of pigs (Bächthold-Stäubli, 1987: vol. 1, 1427). Enormous amounts of food were eaten and drunk. The witches sat on grassy banks and devoured apples, pears, and the flesh of freshly slaughtered roasted ox. The devil himself served the unsalted roast, the

Bockbier

(buck beer), and the wine. From an ethnological standpoint, this relates to a typical archaic Thanksgiving festival: Among primitive people, the “big man” or the chief divides the meat according to strict ritual rules. The tribal kings of the Celts and the Germanic peoples also divided and shared the meat that had been consecrated to the gods, and in this way ensured the good spirits of their followers. In America the head of the household still ceremoniously carves and serves the turkey on Thanksgiving (the third Thursday in November) (Storl, 1997b: 34).

It is significant that the ox meat was served without salt. During the initiation of the youth in the remote “bush schools” of traditional peoples, the food is almost always salt-free. Many shamans—including the farmer-philosopher Arthur Hermes—do without salt because it causes the soul to bind to matter.

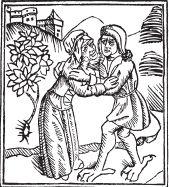

Demon as a witch’s lover. (From Ulrich Molitor,

De laniis et phitonicis mulieribus

, 1489.)

A fertility orgy, which was not very different from other archaic peoples’, became connected with the witches’ festival. When it is said that the participants copulated with goats, wolves, and other animals, it merely emphasizes the unburdened, orgiastic character of fertility festivals. The horned one himself engaged in coitus with the witches. But they—as it says in the trial records—experienced the embrace as rather uncomfortable, for the large, eternally erect penis was ice-cold, possibly because it was an artificial member that was used in fertility magic.

The devil also instructed the participant in all kinds of black arts—weather making, the learning of spells

(maleficii),

the making of magical potions

(veneficii),

and other “evil doings.” Every witch was given a witches’ name and the sign of the devil, which he burned with his goat’s hoof on her back, either on her left shoulder blade or in the small of her back. This was almost certainly a tattoo or brand that had to do with an initiatory test of courage, as was customary in earlier times for the Celts.

For a long time after the conversion to Christianity, the followers of the ancient religions probably still gathered in remote areas, in moors with difficult access, or on mountaintops for Walpurgis Night, Midsummer Day, and other magically loaded times (solstice, equinox, quarter days). The authorities had reluctantly endured these rural fertility rituals until the twelfth century, when the fanatical Cathar sects, with an orientation toward Manichaeism, challenged the Church and made it very insecure. The Cathari (from

catharoi

, meaning “the pure”) taught a stern asceticism and a dualism between God and Satan. Against these heretics Pope Gregory IX initiated the Inquisition, whose agent was the Dominicans. Many suspicious people were made to confess by torture and were punished by the seizure of their property, imprisonment in dungeons, and burning at the stake (Heiler, 1962: 699). Although the Church brutally tortured the Cathari, they took on elements of their adversaries as well—for instance, the concept of Satan as a powerful opponent to God. A machine was set in motion that brought to light the ancient cults and persecuted them as the products of Satanic oaths.

The World Tree

Another Paleolithic concept that still lived on in the inner life of so-called witches was the image of a powerful tree, a World Tree, or a pillar that holds up the sky. From its branches hang the planets and stars. Its roots reach deep down into the bright regions of Frau Holle, into the spring of life, which the world serpent guards and where the mothers of fate (the Norns) sit spinning. The tree is the ladder to the beyond. The gods, ancestors, and ghosts roam up and down the ladder, and sometimes a shaman flies through the branches, crowing like a raven, or like an eagle reaches all the way to the treetops and looks down upon the entire breadth of the universe.

The participants of the witch cult danced circle dances around the ancient oak, ash, or birch tree, which represented the World Tree. The initiates were probably hung from the trees or bound to them so that their souls might travel up and down into the worlds beyond and encounter deities, ancestors, and helpful magical animals. Native Americans and Siberians still bind initiates to such trees. The Plains Indians pierce the flesh of initiates with hooks and bind them to the World Tree while they dance and play eagle pipes and fly into the extrasensory world. As a shamanic god, Odin demonstrated this for the Germanic peoples: For nine days he hung in the tree, starving, thirsty, and sleepless, and drew the wisdom of the runes from Mimir’s well (in the primordial memory). In India it was the king’s son Siddhartha Gotama who fasted for forty days beneath a mighty pipal tree and discovered enlightenment when his spirit spread out in the crown and root regions of existence. Jesus, known as Christ, also hung on a cross-tree on top of Golgotha, the mountain in the middle of the world. In Christian mythology it was the same place where the tree of the fall of man once stood.