Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants (38 page)

Read Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants Online

Authors: Claudia Müller-Ebeling,Christian Rätsch,Ph.D. Wolf-Dieter Storl

A northern Peruvian healer (curandero) sets up his table, or mesa, for a healing ceremony. During colonial times practitioners of this ceremony were persecuted for using witchcraft. This form of ritualistic healing has been preserved in spite of the Inquisition. (Photograph by Christian Rätsch.)

The buds of the poplar (

Populus

spp.), called balm of Gilead in the United States, yield the aromatic tacamathaca resin. In the early modern era this was the main ingredient in the recipe for pharmaceutical poplar salve

(Unguentum populi),

a preparation similar to witches’ salves. (Photograph by Christian Rätsch.)

The threefold “witch goddess” Hecate sits next to her book of magic and invocations, surrounded by her familiars, or animal spirits: ass, owl, lizard, and bat. (Hand-colored print by William Blake, 1795.)

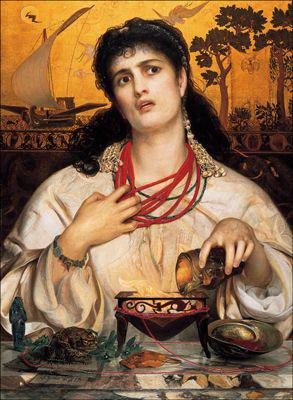

In this pre-Raphaelite painting by the English symbolist Frederick Sandy (1829–1904), the “primordial witch” Medea is depicted executing a magical ritual. For this purpose she makes use of copulating toads, belladonna (

Atropa belladonna

L.), a blood-filled abalone shell, and a censer, and she adds a libation to the compound. Her expression shows that she has already entered another reality. Directly behind her is the garden of Medea. Three of the most important witches’ plants can be clearly recognized (from left to right): snakeroot, belladonna, and monkshood. (

Medea,

oil painting, 1866–1868, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery.)

The Mother of the Witch’s Egg

In the early modern era some mushrooms were also included in the plants of Circe.

101

So it was said of the deer truffle (

Elaphomyces granlutatus

L. ex Pers.) by Matthiolus:

Of the deer truffle the ancients wrote nothing, but indeed it had the power to strengthen unchaste members and Venus-veins, for this purpose one takes a half an ounce of the powder and drinks it with a drachma of long pepper [

Piper longum

L.] mixed in. This drink also increases the milk in women. Burning the mushroom as incense and letting the smoke cover the person from the bottom up quiets the mother in its ascent. The women of Circe also do business with it and use it in love potions (1626: 387).

The witches’ dance took place in a clearing in the woods. In the foreground is an object that can be interpreted either as fly agaric or a covered table. On the left is a

tumulus,

a door to the other world, and above, right, in the tree grins a Dionysian leaf face. (Woodcut from an English chapbook, 16th to 17th century.)

This mushroom, usually called

Hexenei

(witch’s egg) in the vernacular, was used into our era by “evil women” in the preparation of love potions (Aigremont, 1987: vol. 1, 157).

Other mushrooms were also called witch’s egg, such as the fly agaric (

Amanita muscaria

[L. ex Fr.] Pers.) and the stinkhorn (

Phallus impudicus

[L.] Pers.).

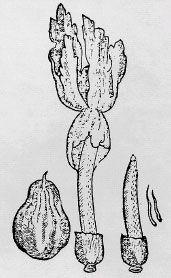

It pushes out of the earth like an egg (devil’s egg, witch’s egg), then the penis rises from this vulva. When it breaks through a horrible odor is released that entices the flies, who then get stuck in the sticky stuff and must lose their life. The penis grows into the shape of a small pillar with a round head (glans) of dirty green color, while the stalk is gray. The final shape resembles precisely an erect penis with the foreskin pulled back. The mushroom has such a shape to thank for its early reputation as an aphrodisiac (Aigremont, 1987: vol. 1, 156).

The witch’s egg of the stinkhorn was also called gout mushroom and was used medicinally. “The gout mushroom was cherished as a remedy for gout in the Middle Ages. It was used in sorcery primarily for love potions, sometimes to create love, sometimes to allay the consequences of illegal love” (Gessmann, n.d.: 49).

The Witches’ Herbs of Linnaeus

In the sixteenth century the French botanists Dalechamp and Lobel had already designated

Circaea lutetiana

as the magical plant of Circe. From there Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) took the name and entered it into his botanical nomenclature. Linnaeus described two species:

Circaea lutetiana,

enchanter’s nightshade

(herbe des sorcières, Circée de Paris, erba-maga comune),

which was distributed throughout Eurasia; and

Circaea alpina

L.

,

alpine enchanter’s nightshade

(Circée des Alpes, erba-maga delle Alpi),

which was native to the Alps.

In addition, there is a natural hybrid:

Circaea

x

intermedia

Ehrh. (

C. alpina

x

C. lutetiana

), intermediary enchanter’s nightshade

(Circée intermédiaire, erba-maga ibrida).

The stinkhorn (

Phallus impudicus

[L.] Pers.) grows out of the “witches’ egg” like an erect penis. The foul-smelling mushroom was considered an aphrodisiac and was once an ingredient in forbidden love potions. (Woodcut from Gerard,

The Herbal,

1633.)

These plants of the Onagraceae family grow in remote shaded places and flower from June to the end of September. Other common names for

Circaea lutetiana

include great witches’ herb, Walpurgis herb, common witches’ herb, Parisian witches’ herb, and magic herb. In Silesia the herb is hung as protection against witchcraft and cattle rustling (Marzell, 1943: 1006ff.). In English the plant is known as enchanter’s nightshade or bindweed nightshade, and the plant has been associated with magical rites (invocations, curses) from very early on. Gerard (1633: 351) had already commented on Lobel’s botanical classification and considered it a mistake, because the effects, which are attributed to the ancient

Circaea lutetiana,

have the same qualities as black nightshade (

Solanum nigrum

L.).

“Hear me, revered goddess, many-named divinity,

You aid in travail, O sight sweet to women in labor;

you save women and you alone love children, O kindly

goddess of swift birth, ever helpful to young women,

O Prothyraia.”

—

FROM THE

O

RPHIC HYMN TO

P

ROTHYRAIA

(A

RTEMIS

E

ILEITHYIA

)

The Garden of Artemis

Artemis was an ambivalent goddess; she could bestow sickness as well as health (Asselmann, 1883: 4). She was a foreign sorceress in the Hellenic world. She was also the goddess of the underworld, as Theocritus noted in a prayer: “You, Artemis, you who also moves the gates of Hades and all which is as strong as that.” Artemis was often identified with Hecate and compared to the Italian Diana. Ephesus was a religious center of Artemis. Once when the opulent city was beset by a plague the oracle of Apollo informed the people that a cult for Artemis Soteira, the “savior,” should be dedicated. In addition, a statue of Artemis with a torch in each hand was to be worshipped. This would cause the wax dolls, through which the plague had been instigated via witchcraft, to melt; thus the illness could be chased away (Graf, 1996: 150).

In Ephesus a many-breasted Artemis was honored. There were also ecstatic mystery cults in Ephesus, whose followers were called

mágos.

The early Christian author Clement of Alexandria polemicized against these heathen rites.