Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants (34 page)

Read Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants Online

Authors: Claudia Müller-Ebeling,Christian Rätsch,Ph.D. Wolf-Dieter Storl

Everything snakelike now evoked, she then

prepares her fruits of evil, heaping them

into a pile: all that the wilderness

near Eryx grows; produce of Caucasus,

those ridges smothered in endless winter,

splattered with Prometheus’ blood

[Ferula communis].

83

The fighting Mede, the flighty Parthian,

the wealthy Arab: she employs toxins

into which they dip their arrowheads

[Aconitum spp.].

She uses juices Uebian ladies seek

Amid the dankness of their black forests

Under an ice-cold sky.

Her hand harvests whatever earth creates in nesting spring

Or when brittle frost balds trees’ beauty,

Forcing life inside itself with cold:

Grasses virulent with dead flowers

[Helleborus niger],

Harmful juices squeezed from twisted roots

[Mandragora].

Mount Athos brought her those particular herbs.

They came from the massive Pindus. That she cut

on a high ridge of Pangaeus; when it lost

its tender, hair-like crown, it left traces

of blood on the sickle blade.

a

Medea is still entirely the shaman, the archaic magician who has a thorough knowledge of botany, medicine, and magic (magical songs).

84

She is not yet the “evil witch” of later eras. She used her knowledge and abilities to protect and heal her friends and allies, and also to harm and destroy her enemies. Those who were afraid of her had reason for their fear; whenever she desired, she could use the “evil eye” (Apollonius,

Argonautica

IV.1670f.). In Euripides’ plays she is addressed as a “lioness” (

Medea

1316), which is possibly an indication that Medea was a skilled shaman who could transform herself into a big cat. During her invocation she bared her breasts,

85

gave her hair a lively toss, and held a snake in each hand (Seneca,

Medea

). Thus she completely resembled the Minoan snake goddess of Crete. Later she became immortal and ruled as queen of the witches and the bride of Achilles over the Elysian fields (Ranke-Graves, 1984: 577).

Medea’s beauty—Hesiod called her the “pretty-footed Medea” or the “pretty-eyed”—and her erotic skills and magical arts had already fascinated the ancient poets. But she also inspired fear and disgust. Euripides dedicated an entire tragedy to her. Ovid did as well, and also voluptuously described some of Medea’s feats in

The Metamorphoses;

from his play

Medea,

however, only one verse remains (Binroth-Bank, 1994; Heinze, 1997). The poetry of Euripides was used as the model for countless Medea workings in world literature. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries many operas were written that took on the Colchian sorceress. The allure of Medea still radiates today. For example, she has become a current topic in women’s literature. Not without reason did Ursula Haas produce a

Freispruch für Medea

[Aquittal for Medea] (1991), which Rolf Liebermann set to music as an opera (1995).

86

Medea, the blond Colchian woman with a “godlike head,” came from a country inhabited by “black faced” barbarians (Apollonius,

Argonautica

III.828ff.). Her grandfather was Helios,

87

the great demiurge who cracked open the Orphic world egg (cf. Ranke-Graves, 1985). This genealogy had already been reported by Hesiod. Medea, Circe, and Hecate belong to the clan of Helios/Sol.

88

In other words, witches are the children of the sun! According to Hesiod, Medea bore a son named Medeios from her liaison with Jason the Argonaut, “who was raised in the mountains by Chiron” (

Theogony

1001). Thus the mother who was well versed in magic had her child trained from birth in the healing arts by the shamanic centaur Chiron, who also raised Hercules.

The Magic Salve of Medea

The “all magic mediator” Medea was a famous healer: “And with oil medicating simples against stark pain [she] gave them for his use” (Pindar,

Fourth Pythian Ode

221f.). Medea apparently learned the art of making salves from Prometheus: the

Promethion

, the “Prometheus plant,” is one of the most important magical substances

(pharmaka)

of Medea. This “plant of Medea” was intriguingly identified by Clark (1968) as mandrake

(Mandragora).

The “substance, which, as people say, is named after Prometheus,” had wonderful powers.

If a man should anoint his body therewithal, having first appeased the Maiden [Persephone], the only begotten [of Demeter], with sacrifice by night, surely that man could not be wounded by the stroke of bronze nor would he flinch from the blazing fire; but for that day he would prove superior both in prowess and in might. It [this plant] shot up first-born when the ravening eagle on the rugged flanks of Caucasus let drip to the earth the blood like ichor

b

of tortured Prometheus. And its flower appeared a cubit above ground in color like the Corycian crocus, rising on twin stalks; but in the earth the root was like newly-cut flesh. The dark juice of it [the pharmakon], like the sap of a mountain-oak, she had gathered in a Caspian shell to make the charm withal, when she had first bathed in seven ever-flowing streams, and had called seven times on Brimo [Hecate], nurse of youth, night-wandering Brimo, of the underworld, queen among the dead, in the gloom of night, clad in dusky garments. And beneath, the dark earth shook and bellowed when the Titanian root was cut; and the son of Iapetus himself groaned, his soul distraught with pain (Apollonius,

Argonautica

III.843ff.)

Medea gave precise instructions on how to use the magical salve—just like the witches’ salves. “She said to Jason the Argonaut, ‘And at dawn steep this charm in water, strip, and anoint thy body therewith as with oil; and in it there will be boundless prowess and mighty strength, and thou wilt deem thyself a match not for men but for immortal gods’” (Apollonius,

Argonautica

III.1042ff.).

Thus strengthened, the hero Jason could confront his duties to carry out the initiation into the mysteries of Hecate. Only conquering the dragon who guards the tree of knowledge remained, and here the priestess of the Great Goddess stood effectively at his side. “But she [Medea] with a newly cut spray of juniper [Arkeythoy,

Juniperus phoenica

L.], dipped her substance

[pharmaka]

into a mixture

[kykeon]

and sprinkled it undiluted in the eyes [of the dragon] using the magical formulas, and the enveloping intensive aroma lulled him to sleep” (Apollonius,

Argonautica

IV.156ff.).

The kykeon was the key to the mysteries of the Great Goddess (Wasson et al., 1984). The kykeon was a mixed drink

89

that was prepared from the pharmaka of the goddess—from opium, for example.

The Plants of the Atonement Sacrifice

Medea burned a funeral pyre as an incense in order to practice her magical arts; the magical smoke consisted of juniper wood,

90

kedros (

Juniperus oxycedrus

L.)

,

91

rhamnos (buckthorn), and poplar—all plants that were already growing in Hecate’s garden (Dierbach, 1833: 203).

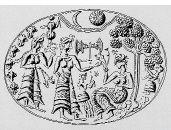

The Great Goddess, Deo or Demeter, sits bare-breasted beneath a sacred tree and offers her followers or priestesses an opium capsule. (Copy of a Minoan gold insignia ring from Mykonos.)

Alkanet (

Anchusa tinctoria

L.) is one of the magical plants of Medea. (Woodcut from Gerard,

The Herbal,

1633.)

In the early modern era the ancient magical plant ephemeron was equated not only with autumn crocus but also with loosestrife (

Lysimachia ephemerum

L., Primulaceae). This plant was cooked in wine and recommended for toothaches. (Woodcut from Gerard,

The Herbal,

1633.)

For their atonement sacrifices, in order to ritually cleanse themselves, participants used the following additives.

The experienced Medea also brought to me many magical plants,

which she picked from the soil of the sacred shrine,

Then I quickly prepared a joyous image beneath the veil,

threw it up to the woods, and finished the sacrifice of the turning point,

Three very dark offspring of the she-dogs worshipped the gods.

With the blood was I mixed chalkanthos herb with strouthejan,

Knekos also, and onions too, along with the red anchusa,

Also the potent psyllejon and chalkimos.

Then with the mixture I filled the stomach of the dog, and laid her on the funeral pyre.

—

O

RPHIC

S

ONGS OF THE

A

RGONAUTS

(958FF.)

All of these plants, the “magical plants of Medea,” were important medicines in antiquity.

The Elixir of Youth

Since time began humans have harbored the desire for eternal youth, even for immortality. The people of antiquity also shared these desires. In Sparta the love goddess Aphrodite is called Ambologera, “the one who dispels age” (Kerényi, 1966: 66). The abilities of being able to cure disease, make the old young again, make rain, forge pacts with the dead, and write poetry were attributed to the ancient magoi shamanic figures, for example, Orpheus, Pythagoras, and the brilliant figure of Empedocles (fifth century B.C.E.) (Luck, 1990: 20). Particularly famous in the ancient literature is the drink of youth, or, more precisely, the “rites of Medea.”

92