Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants (32 page)

Read Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants Online

Authors: Claudia Müller-Ebeling,Christian Rätsch,Ph.D. Wolf-Dieter Storl

As far back as the Middle Ages the Thessalian witches have been endowed with cannibalistic tendencies.

70

It was said that they had an enormous appetite for human flesh, used body parts for making love potions and death drinks, and even gnawed on corpses.

71

That is why there were cemetery guards who prevented the witches access to the dead. Eating human flesh or human entrails should—as Plato and after him Pausanias (

Itinerary of Greece

8.2, 6), reported—lead to one’s transformation into a wolf (Burkert, 1997: 98ff.). Petronius described how a man transformed himself on the night of the full moon.

When I looked back at my companion, he stripped off and laid all his clothes by the side of the road. … He pissed round his garments, and suddenly changed into a wolf. … He turned into a wolf, and then he began to howl, and then he disappeared into the woods (

The Satyricon

62).

“The plant Basilica grows on such places where the snake Basilicus is found. … those who carry [the plant] with him will have domain over this snake, and no evil eye nor any problems will ever harm them.”

—

M

EDICINA ANTIQUA,

FOLIO 117R

The Thessalian witches had further traits of a scatological nature. They allegedly consumed excrement and used all sorts of animal feces and urine for the preparation of their magical and medicinal remedies (their

pharmaka

or

venena

)—an early form of the so-called

Dreckapotheke

, the “filth pharmacy.”

72

In the descriptions passed down from antiquity Thessalian witches are even said to “piss long and hard in the face” of a man in order to bewitch him (King, 1988: 17). Today such behavior would be condemned to the realm of bizarre pornography or discussed in the context of urine therapy.

However, the Thessalian witches could also, thanks to their magical arts, produce brews that filled the drinker with Dionysian joy. Ovid described how a drink of this kind was prepared.

The three-faced and six-armed Hecate with her serpents. (Copy of a classical Gemme.)

Then [Tisiphone] yanked two snakes from her hair and with a toss of her filthy hand threw them at the pair. They slithered inside the garments and down the sheets of Ino and Anthamas and breathed their morbid breath upon them, but did not wound their bodies: It was their minds that felt the savage blows. Tisiphone [the fury] had also brought a monstrous mixture of deadly poisons: from Cerberus’ mouths [henbane, monkshood], venom from the monstrous Echidna [the mother of Cerberus], the wandering blankness of darkened mind, crime, tears [resin, amber], and an insane craving to kill, ground up together, mixed with fresh blood, boiled in a bronze vat, and stirred with a green stick cut from a hemlock tree” (

The Metamorphoses

IV.495ff.).

The saga about the founding of Eritrea through the conquest of Knopos and the Kodriden reports of such a drink.

Knopos had brought a priestess of Hecate from Thessalia, who in light of the enemies, the former Eritreans, prepared a bull sacrifice. The horns of the animal were gilded, it was decorated with rushes and led to the altar. But he had been given a substance which drove him mad and suddenly the bull broke loose and ran snorting raucously over to the enemies. They caught him and sacrificed him and had a party with his meat. Then all were seized by insanity and were easily taken by the attacking Kodriden (Burkert, 1997: 181, following Polyainos,

Stratigimata

8.43).

In short, the image of the Thessalian witch was that of a humanized Hecate.

73

Ancient Chinese symbol of rebirth, with serpents and a sun wheel.

The emblem of the Sumerian physician-god Ningizzida shows two serpents wrapping around a cosmic pillar or the trunk of the World Tree, flanked by two fantastic hybrids. (Illustration from Heuzey,

Catalogue des Antiquités Chaldéenes,

1902.)

From the Snakes of Hecate to the Staff of Asclepius

Many snakes lived in the garden of Hecate. They were sacred to the goddess. For snakes are as ambivalent as Hecate herself; with their poison they can heal and they can kill. That is why the two snakes are one of the most important attributes of the witch goddess. One symbolizes healing and health; the other sickness and death. Snakes, which were protected in the temple, were also used for divination and prophecy. Perhaps the famous bare-breasted snake goddesses of Crete were forms of Hecate or her priestesses. The oldest oracle of Delphi, the “navel of the world,” was Pythos, a female serpent or dragon. Her spirit lives on in Pythia, the prophetic priestess in the temple of Apollo. According to a Delphic myth it was a smoke that rose from the rotting corpse of the python killed by Apollo that Pythia inhaled in order to fall into a prophetic trance (Rätsch, 1987b). Snake handling and snake charming were already part of the witches’ arts of late antiquity. “The people of Absoros could not cope with an endless number of snakes. At their entreaties Medea [who flew to Colchis on dragon’s wings] gathered them up and put them in her brother’s [Abystros] tomb. There they still remain, and should any go outside the tomb, it pays with its life” (Hyginus,

Myths

).

As Hecate was a goddess from Asia,

74

it is very likely that she introduced the tantric symbolism of the snakes into archaic Greece. In tantra the serpent stands for the feminine sexual energy; in this aspect it was called

kundalini

. The kundalini snake is equal in its form to a cobra.

75

At the same time it is a manifestation of the Great Goddess, especially her dark aspect, which is expressed in the figure of Kali. In the Himalayan regions and India, Kali is still considered to be a “witch goddess” (Kapur, 1983). She is still worshipped in secret rituals, invoked by witches, and nourished with blood sacrifices.

76

In general Hecate and Kali have many similarities.

77

Both have six arms, both carry torches as an attribute, and both hold daggers in their hands. Both reveal the dark side of the universe, both have destructive but rejuvenating traits—just like their symbolic animals renew their skin. Both have the power to heal and to kill.

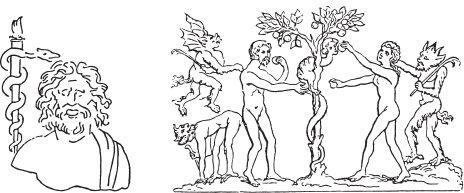

Left: The ancient healing god Asclepius/Asklepios with the asclepian staff made of a torch enwrapped by a serpent. (Modeled after a relief on the ancient harbor wall on the Tiber River in Rome.) Right: Adam and Eve in paradise with the tree of knowledge, which has the diabolic serpent wrapped around it. (Medieval woodcut.)

In the Asian tantra cult a snake wrapped around stone, an egg,

78

a staff, or a phallus represents the feminine energy that is released during the sexual union between god and goddess, man and woman, leading to an altered state of consciousness (Müller-Ebeling and Rätsch, 1986). In ancient India and ancient China the entwined snakes in combination with disks or wheels are a symbol of rebirth and of the eternally regenerating creation. In Mesopotamia the symbol of the Assyrian medicine god Ningizzida (third century B.C.E.) was a snake staff. In ancient Greece the snake wrapped around a staff or a torch became a symbol of the healing god Asclepius, and eventually a symbol for the medical arts in general. “The snake of Asclepius was considered the primordial form of the god and appears many times as his representative in temple healings. From classical antiquity until late antiquity the snakes generally enjoyed great respect and were often kept as house pets” (Kasas and Struckmann, 1990: 22).

Only the monotheists feared and demonized snakes. It was a serpent that seduced Eve, who then seduced Adam to eat the forbidden fruit of the tree of paradise. In tantra humans strive to become like gods and goddesses, to experience the mystery of being, and to receive divine knowledge. This is forbidden to believers of monotheism. Snakes not only were the personification of the devil but also became the primordial image of evil. That is why in many descriptions of witches in the modern era snakes are used as ingredients for magical potions.

The staff of Asclepius was originally the symbol for the tree of knowledge. In the healing cult of Asclepius it became the symbol of ritual medicine. In late antiquity it was considered a symbol of hermetic alchemy and the divine messenger Hermes/Mercury, until ultimately it was reinterpreted as the symbol of scientific academic medicine.

Snakes As Medicine

As is shown in the images on ancient vases, snake venom was taken as medicine or perhaps drunk as an intoxicating additive in wine. In his medicinal teachings Dioscorides wrote: “The flesh of the viper [from

Vipera aspis

Merr. and

Vipera ammodytes

Dum. et Bibr.] cooked and eaten gives one keen eyes; it is also a good remedy for neuralgia and keeps the swelling of the lymph glands down. … Some also say that one can reach an old age by eating it. … Snakeskin cooked in wine is used as an injection against earaches and as mouth rinse for toothaches. It is also included under the remedies for eyes, mainly from the viper [Asclepius snake,

Coluber aesculapii

Sturm]” (

Materia medica

II.18, 19).

Next to opium, viper flesh (in particular from the aspic viper,

Vipera aspis

) became known as a universal remedy and antidote called

theriak

and

mithridatium

during antiquity, late antiquity, and the Middle Ages. The recipe, which included up to sixty herbs, can be traced back to Andromachus, the doctor of the emperor Nero (C.E. 37–68), King Mithridates of Pontos (132–63 B.C.E.), and Celsus (c. first century B.C.E.). Snake flesh is considered an antidote to poison. Theriak can still be purchased in pharmacies, but without either of the main ingredients: viper flesh and opium.