Writing the Breakout Novel Workbook (26 page)

Read Writing the Breakout Novel Workbook Online

Authors: Donald Maass

Conclusion:

For a novel to feel big, big things must happen: irrevocable changes, hearts opening, hearts breaking, saying farewell to one well loved whom we will never meet again. Create these moments. Use them. They are the high moments that make a novel highly dramatic.

Bridging Conflict

D

id you ever arrive early for a party? It's awkward, isn't it? The music isn't yet playing. Your host and hostess make hurried conversation with you while they set out the chips and dip. You offer to help, but there's nothing you can do. You feel dumb for getting there too soon.

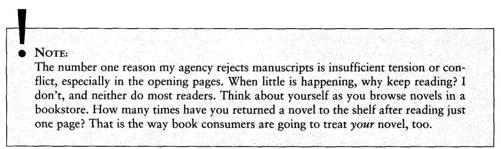

That's how I feel when I read the opening pages of many manuscripts. Pieces of the story are being assembled, but nothing is happening just yet, and often the guest of honor, the protagonist, hasn't arrived. In fact, no one I like has shown up yet. Later on the story will be in full swing, but for now I wonder why I bothered to accept this invitation.

Bridging conflict is a story element that takes care of that. It is the temporary conflict or mini-problem or interim worry that makes opening material matter. There are thousands of ways to create it. Even the anticipation of change is a kind of conflict that can make us lean forward and wonder,

What is going to happen?

Brian Moore is one of our more reliable novelists, having brought us

The Statement, The Emperor of Ice-Cream,

and

The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne,

among many others. In

The Magician's Wife,

Moore spins the story of Emmeline Lambert, who in Second Empire France is married to a stage magician and inventor, Henri, who is recruited by the government to so dazzle an Algerian marabout (living saint) with his illusions that, outclassed, the marabout will be unable to wage a holy war. That, anyway, is the plan.

However, Emmeline does not immediately know that. Her husband tells her only that they have been invited by the Emperor to attend a weeklong

series,

a lavish royal house party. Emmeline, who is from a modest middle-class background, is terrified by the prospect and raises objections: "A week? What are we going to wear? We don't belong in that world."

She also worries that Henri is being asked in order to perform, that she has no ladies maid and he no valet. Her husband overrules all her objections, stating that it is an honor to be invited, that they can afford the clothes, and in any event the Emperor has summoned him on a matter of national

importance. This simple argument nicely supplies the tension that holds our attention until the next stage of the game.

I hate most prologues. Typically, they are "grabber" scenes intended to hook the reader's attention with sudden violence or a shocking surprise. Mostly they do neither, not because they lack action but because the action is happening to characters about whom I know little; indeed, it is common in prologues for novelists not to name the players. When a nameless victim is killed by a faceless sicko . . . well, honestly, why should I care? I can see that twenty times a night on television.

And then there are prologues like that in Steve Martini's courtroom thriller

The Jury,

which opens with the introduction of a beautiful and ambitious ex-model turned molecular electronics researcher (yeah, I know) in San Diego named Kalista Jordan. As she relaxes one evening in a hot tub at her apartment complex, she hears unusual sounds in the courtyard around her. A killer is creeping up on her.

Many authors would be content with the low-grade suspense that generates, but Martini doesn't leave it at that. He adds tension by taking us inside Kalis-ta's head to reveal the difficulties she is having at her research lab:

This evening she'd had another argument with David. This time he'd actually put his hands on her, in front of witnesses. He'd never done that before. It was a sign of his frustration. She was winning and she knew it. She would call the lawyer and tell him in the morning. Physical touching was one of the legal litmus tests of harassment. While she was sure she was more than a match for David when it came to academic politics, the tension took its toll. The hot tub helped to ease it. Enveloped in the indolent warmth of the foaming waters, she thought about her next move.

It emerges that Kalista seeks to be the director of the lab and its twenty-million-dollar annual budget. To reach her goal, she has undercut her boss's authority on part of the funding and has developed allies in the chancellor's office.

What will be the downfall of Dr. David Crone (the David mentioned above), though, is his complete lack of tact. When Kalista is murdered, the police seize on him as the suspect with the best motive. Crone does himself no favors with his poor social grace. It is up to Martini's crack attorney, Paul Madriani, to clear the name of this difficult client. The first chapter picks up the trial midstream, but meanwhile Martini has held our attention and simultaneously has won sympathy for the defendant by showing us the victim's true colors while she was alive.

One of the most sustained examples of bridging conflict in recent fiction can be found in Daniel Mason's tour-de-force debut novel

The Piano Tuner.

This historical tale tells of a London piano tuner, Edgar Drake, who specializes in rare Erard grand pianos. Drake is recruited to journey to upper Burma to tune an Erard that was transported to the far jungle at the insistence of an eccentric army Surgeon-General and naturalist, Anthony Carroll, whose whims are tolerated by the army only because he is able to keep the peace among the local tribes. Drake is intrigued by Carroll's reputation and the challenge of getting there.

He sets off, but it is almost two hundred pages before Drake reaches Carroll. The trip from London, across the Mediterranean by steamship, over the Red Sea, though India by train, by ship to Rangoon, then on to Mandalay, there to languish for many days due to bureaucratic delays, should, by rights, be nothing but boring travelogue. Mason, however, fills the journey with bridging tension of every type.

There is Drake's longing for his wife, and his long letters home telling of his maladjustments to the strange conditions he meets. He meets strangers with mysterious stories, embarks on a tragic tiger hunt, and encounters friction in the barracks. His adventures escalate tales of Carroll—from both those who hate him and those who venerate him—and at last, in Mandalay, he meets Khin Myo, the mysterious Burmese woman who becomes his guide and with whom he becomes—tragically, it turns out—infatuated.

Mason does not indulge in mere travelogue; instead, he turns Drake's journey into a series of mini-stories. The dread and fascination Drake feels about meeting Carroll gradually builds, too, making the trip itself one that I, for one, thought could only end in a sense of anti-climax. I was wrong. Carroll proves to be every bit as large as anticipated.

How do you bridge from your opening page to your novel's main events? Do you just get us there, filling space with arrival, setup, and backstory? Or do you use the preliminary pages of your manuscript to build tension of a different sort?

_____EXERCISE

Developing Bridging Conflict

Step 1:

Does your novel include a prologue that does not involve your protagonist, or one or more opening chapters in which your hero does not appear? Move your hero's first scene to page one.

Yes, really do it. See how it feels.

Step 2: |

|

Step |

|

Step 4:

Open your manuscript to page one. How can you make that bridging conflict stronger at this point?

Make a change that makes the conflict more immediate and palpable.

Step |

|