You Majored in What? (19 page)

Read You Majored in What? Online

Authors: Katharine Brooks

In Chapter 5 you started creating images of your future—the Possible Lives you might lead. The ideas you developed are not necessarily predictions of what will happen, but rather are probable or possible glimpses into the future based on what you currently know. The quote above from novelist E. L. Doctorow was taken from an interview where he was asked if he plotted out his stories ahead of time. As you can tell, he was content to let the story develop as he wrote. You can plan your life the same way. As you start developing your plans, keep the pressure off and your anxiety level down by remembering a key tenet of chaos theory: the further into the future you’re trying to plan, the less accurate your plan will likely be. So in this chapter you’re going to plan only as far as your headlights will permit, organizing and reducing the chaos. And even better, by the end of this chapter, no matter where you are right now, you will have an amazing answer to

THE QUESTION

.

Planning your future isn’t a once in a lifetime activity. It’s a series of decisions and experiments you’ll be crafting throughout your life. The plans you’re about to develop are designed to help you be focused as well as flexible, not only about your career but also about any other aspects of your life you’d like to change. You will learn to set up your environment to make achieving your goals natural and easy. Through this approach to planning you’ll be able to take advantage of, and be resilient to, any changes.

In order to set up your plan, you need to know two things:

where you are

and

where you’re going.

In this chapter we’re going to assess both. The metaphor I like to use involves a GPS tracking system. Maybe you have one in your car. You enter your starting point and your destination, and the computer guides you all the way. Even if you ignore it and make a turn that’s not in the original plan (notice I’m being very careful here not to say “wrong turn,” because there are no wrong turns), the GPS tracker just resets the plan to get you back on track to your destination. If you change your mind and want to go somewhere else, it will show you how to do that as well. The first section of this chapter focuses on where you are. In this section you’re going to take stock of all the knowledge and information you’ve accumulated up to this point: what you’ve acquired by doing the exercises in the first four chapters.

In the second portion of this chapter, you’re going to examine where you’re going by looking at the Possible Lives you’ve created and mapping out your plan to get to them. If you’ve ever avoided goal planning because it is usually presented in a boring and linear manner with lots of rules, you will find possibility planning and intention setting much more interesting. Maybe even fun. After all, goal setting is not a one-size-fits-all activity. Your experiences are too unique for that. The plan you develop will fit your style, not someone else’s. There are so many ways to get from where you are to where you want to go that it only makes sense to pick a way that you’ll enjoy and will work for you.

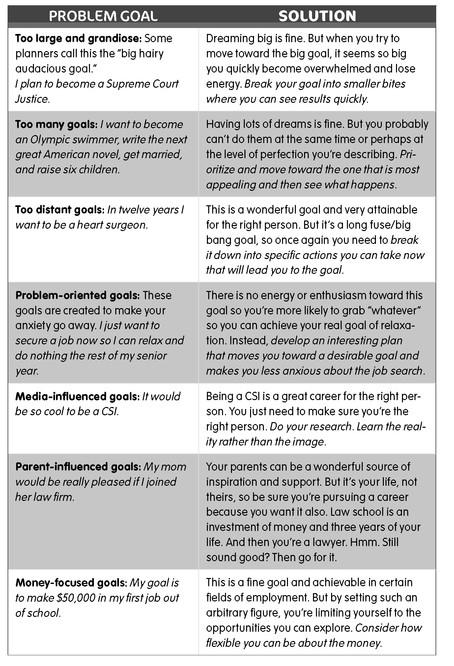

Any type of goal-setting system has built-in roadblocks, so before you set the course for your goals, let’s consider some of the roadblocks that can wreck your plans before you even start. The chart below illustrates the most common goal-setting challenges and some quick ways to avoid or overcome them.

Baby steps get on the elevator . . . baby steps get on the elevator. . . .

Ah, I’m on the elevator.

—BILL MURRAY

AS BOB WILEY IN WHAT ABOUT BOB? (1991)

WHERE ARE YOU? ASSESSING THE PRESENT

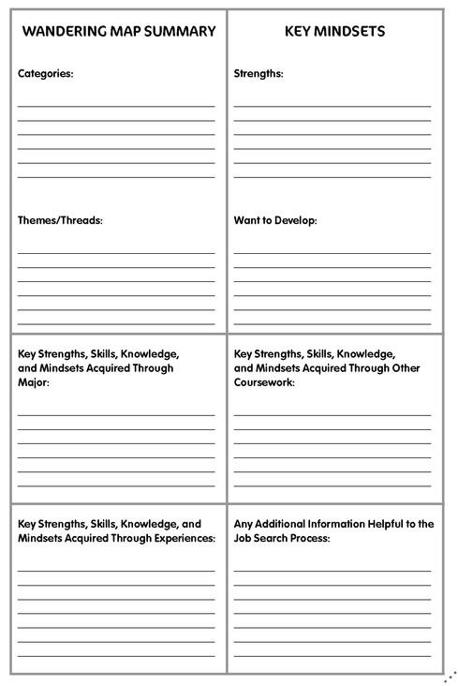

It’s time to compile all the information you’ve acquired so far. You have at least four main sources to consider:

1. Your

Wandering Map

categories, themes, and threads (from Chapter 2)

2. Your

key mindsets,

including the ones that are your strengths and the ones you want to build (Chapter 3)

3. The

strengths, skills, knowledge, and mindsets

acquired through your major, your additional coursework, and your experiences (Chapter 4)

4. The

Possible Lives

you’d like to lead (Chapter 5)

This information is your gold mine; it contains the unique strengths you possess that will interest employers and graduate schools. You will want to keep your gold mine in mind as you go through the rest of the book to arrive at your final destination.

On the next page you will find a form to help you gather the information you’ve acquired in one place. You can fill in the form or create a similar list in your notebook. Note: If you’ve skipped some of the chapters or exercises, this would be a good time to go back and complete them so you’ll have the best information as you start making your plans.

WHERE DO YOU WANT TO GO? CHOOSING YOUR FUTURE

“Ghost of the Future,” he exclaimed, “I fear you more than any spectre I have seen.”

—CHARLES DICKENS,

A CHRISTMAS CAROL

The Wise Wanderings system offers three approaches to planning your future based on the clarity of your vision. One way to determine which system will work best for you is to simply read all three approaches and then select the one you prefer. Or you can base your selection on your response to the following question:

What would you like to do after you graduate?

If you honed in on one Possible Life in Chapter 5, and your answer is something like one of these:

• I am going to law school.

• I want to be an investment banker in New York City.

• I’m going to teach history to high school students.

• I’m going to get my Ph.D. in economics and become a college professor.

• I’m going to medical school.

• I want to work in retail merchandising.

• I’m going to teach English in Japan.

• I want to work with adolescents in a nonprofit center.

then you have developed a clear and reasonably certain goal and can move forward with the Probability Planning (Wandering Strategy 1) opposite.

If your answer is more like the following:

• I’ve got two ideas but they have nothing in common (pendulum attractors).

• I’m going to teach English abroad or maybe work in a kibbutz or do something in the nonprofit area.

• I selected several Possible Lives but I’m not sure which to follow first.

• I want to go to graduate school but I’m also interested in several different jobs.

• I have several career ideas but I want to do something interesting first, such as traveling to South America.

then you will want to try Possibility Planning (Wandering Strategy 2), which starts on page 146.

Finally, if your answer is general or nonspecific, such as one of these:

• I have no idea what I want to do

• I want to work with people.

• I want to work in business.

• I’d like to work internationally.

• I want to work in a nonprofit setting.

then you will want to try Seeking the Butterfly (Wandering Strategy 3) described on page 152.

PROBABILITY PLANNING (WANDERING STRATEGY 1)

Probability Planning is traditional goal-setting planning with a chaos theory twist. Chaos theory tells you that even though your goal may seem etched in stone, as you move toward it you will learn new information and it may change. Probability Planning means you focus on that one option (“I will be at Harvard Law School in three years”), but as you move toward that option, you broaden your search to include other related options. After all, in most decisions or choices, you aren’t completely in control. If you could just will yourself into Harvard Law, then it would likely happen. But chaos theory reminds us of the complexity of the admissions process: how many other students are applying this year to Harvard, their grade point averages, the type of student Harvard is seeking (and are you their type?), the average LSAT score for admission, and so on. You don’t have control over all the variables, and since you don’t have 100 percent control, you will want to develop some secondary options. In this example, specifically, you will want to identify other law schools you’re willing to attend. If you’re determined to attend Harvard and no other law school, then what would Plan B look like? Perhaps a year off after graduation to build experience?

Because here’s an even wilder option: suppose senior year comes along and you suddenly realize you don’t want to be a lawyer? Oops. Now what do you do? No problem. Possibility Planning (in the next section) has you covered. But for the moment you are fairly certain about your decision, so use the Probability Planning method. You can always use a different system if new information or knowledge emerges.

On pages 142-143, you will find a Probability Plan Worksheet that you can adjust to fit your needs. While at first it looks a little complicated, it’s actually very simple to use and easy to follow.

1. Start by brainstorming the key steps you need to take to attain your goal. If you’re having trouble with this step, you probably don’t know enough about the subject. It’s time to research or speak with someone who can help you.

2. Write the steps in the first part of the chart below (or on a separate piece of paper). At this point, don’t try to put them in any particular order. Just write them down as you think of them. The chart has an arbitrary number of twenty steps—you may have more or less, so adjust it as needed.

3. Determine the time frame from now until you plan to achieve your goal. For instance, if you goal is to work for the Peace Corps after graduation and you just finished your sophomore year, you have approximately two years before you will get there. That gives you a lot of time to prepare to be the best candidate for the job. On the other hand, if you’re a first semester senior and your goal is to join the Peace Corps, you only have a few months, so you will need to work quickly to become the best candidate.

4. Review your steps to achieve the goal and renumber them beginning with the first step to the last step. Break the steps into small groupings on the chart and write in a specific deadline when you will achieve the various steps. Again, the grouping of five steps is arbitrary. Only use what you need, or add more if needed. You can start from where you are now and go forward to your goal, or you can start with the goal and work backward on your planning sheet, whichever you prefer.

As you set up your plans, keep your academic calendar in mind—don’t schedule steps toward your career during exam week or when papers are due. Don’t try to crowd too many deadlines into one time period. And don’t set goals for Saturday night (unless they’re fun, of course). You can assume obstacles will come up. Walk around them. You can also assume that you might change your goal, in which case you just go back to pages 138-139, determine where you are, and use the system that best applies to your new thinking about the future.

You know what the best part of Probability Planning is? When you’re asked

THE QUESTION

, you’ll have no trouble saying, “I plan to _ and I’ve outlined my plan to get there.

After the Probability Plan work sheet, you’ll find a sample plan developed by Madison, a sophomore who will be graduating in May 2011. She wants to become a lawyer, but hasn’t decided which school she’d like to attend or what area of law to pursue. She has identified ten steps, so that’s where she’s starting, but she may add more later as she learns more about the process.