You Must Remember This (23 page)

Read You Must Remember This Online

Authors: Robert J. Wagner

The influence of these publicity men eventually spread over the town. If journalism is all about figuring out who can give you the information you need for a story, the job of head of publicity at a movie studio is about figuring out how to keep the person who has the information from spilling it. Half the time, a press agent is really a suppress agent. In her memoirs Hedda Hopper wrote about how MGM spent nine thousand dollars keeping the reputation of one of its stars intact after he was caught propositioning an underage boy. Hopper didn’t mention his name, but it was William

Haines. On those rare occasions when a star actually did make the papers for bad behavior—Robert Mitchum for smoking marijuana, Robert Walker or Frances Farmer for being drunk and disorderly—it was usually either a setup (Mitchum) or the studio washing its hands of a performer that was just too damn much trouble (Farmer).

Usually, though, every bar patronized by any actor knew that if an actor got drunk and disorderly, proper procedure involved calling the studio, not the cops. A publicist would show up quickly, some folding money would be exchanged, and the offender hustled away. If the star was actually taken in by the police, they in turn would call the studio and the star would be quietly taken home, with a corresponding standing order for a large batch of tickets for the next fund-raiser to the Police Athletic League. Charges were rarely brought.

The studios didn’t believe they were exercising influence; they believed they were simply accepting favors from old friends. For a time Harry Brand even gave the dangerous gossip columnist Walter Winchell an office on the Fox lot, which made it unlikely that Winchell would write anything destructive about any of the stars.

Harry retired in 1962, in the middle of the

Cleopatra

debacle. The studio was pouring all its resources into the Rome location of the wildly overbudget epic, and the Fox publicity department was cut in half. (Not coincidentally, this was also the time when I made the decision to leave the studio, which focused on nothing but getting

Cleopatra

finished. Everything and everybody else had to fend for themselves, and I decided I could do better on my own, which indeed proved to be the case.)

Harry Brand died in 1989. He wanted no service, and requested that people who cared about him make a contribution to the Motion Picture and Television Country House and Hospital in Woodland Hills. It was a typically generous gesture on the part of one of the genuinely good men of the movie industry, one who just happened to also know a great deal of the secret history of Hollywood.

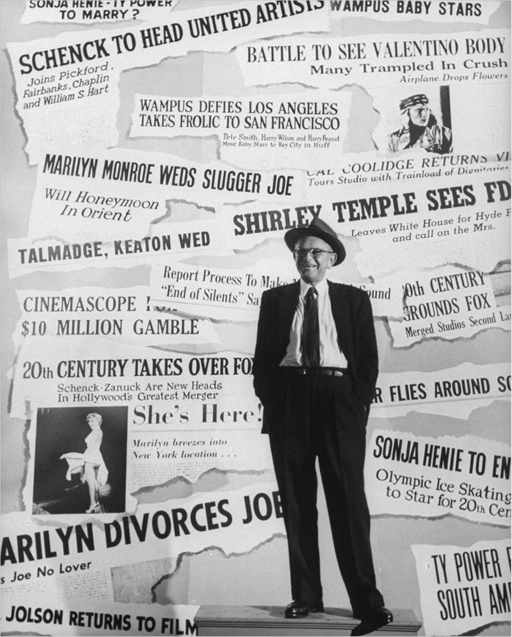

Press agent Harry Brand posing for a picture.

Time + Life Pictures/Getty Images

As for Howard Strickling, he maintained his position with the people at MGM long after they, and he, had retired. It was Strickling who organized Spencer Tracy’s funeral. Spence had left the studio a good dozen years before his death, and Howard was retired by then, but the family knew that only one man could organize the funeral in a way that Spence would have wanted. True to

form, Howard kept the press away in a manner that didn’t enrage them, and managed the entire day masterfully.

(That was typical of the people who had made up the MGM hierarchy: Kay Thompson, the vocal coach, was always on call to help out at MGM for years after she left the studio, and I believe Margaret Booth did a lot of “consulting” long after she was no longer the head of the MGM editorial department and had gone to work for Ray Stark.)

Another subculture that swarmed around the movie business consisted of press agents. One of the longest-serving, as well as one of the best, was Richard Gully. Richard was illegitimate, a cousin of Anthony Eden’s, and extremely British. How he ended up in Hollywood I don’t know, but Richard was involved in higher duties than just placing items in columns or keeping items out of them.

One of his gifts was introducing clients into Hollywood society. He worked for Jack Warner for a long time, and it was Richard who made a lady out of Ann Warner and a half-assed gentleman out of Jack. Richard knew everybody, and knew not only where all the bodies were buried, but what size shovels had been used. Yet he never said a word about any of it. My wife, Jill, adored him, as did most people who knew him.

These publicity men had to have their noses to the wind at all times; at the very least, they were street smart, and some of them were considerably more than that. Roughly speaking, their job could be divided into two parts: the nominal keeping of a star’s name in front of the public, and crazed ballyhoo. The master of the latter was a man named Russell Birdwell, who masterminded David Selznick’s search for Scarlett O’Hara, which made the entire nation even more conscious of

Gone with the Wind

than they would have ordinarily been.

Birdwell was a freelancer, and very expensive; he would charge a client as much as a hundred thousand dollars for a year of his services, plus overhead. He was brilliant but erratic. One day Carole Lombard heard a director complaining about the taxes he had to pay; she told him that, considering how much money she made, she felt that her tax bill was pretty reasonable. Birdwell promptly forwarded the remark to the IRS, which publicized it, and before you knew it Carole Lombard was being praised for her patriotism in being happy to pay her taxes.

It was Birdwell who devised the publicity campaign that promoted Jane Russell in

The Outlaw

, which centered almost completely on her chest, and who also handled the equally over-the-top campaign for John Wayne’s

The Alamo.

He likewise devised an innovative campaign for the Burt Lancaster film

Elmer Gantry

, having “Elmer Gantry was here” written all over sidewalks in Los Angeles and New York. The movie didn’t have anything to do with sidewalks, or even with cities, but Birdwell inserted the movie’s existence into the public’s consciousness in a way that made him worth every penny he got.

In the early 1950s, when I became a star at Fox, the studio protected us very well. If a fan magazine was doing a feature, it was controlled by Fox. Back then, when Natalie and I went to our favorite restaurants, La Scala and Chasen’s, there would often be guys standing outside asking if they could take a photograph. But it was all very well mannered, and we always let them shoot. It was nothing like it is now, with roving wolf packs of photographers and videographers trolling the streets of LA.

By the middle of the decade, though, the publicity business had

begun to change. Before then, the studios wouldn’t muscle Hedda or Louella, because they didn’t have to; rather, they would finesse them. In return for keeping quiet about something the studio didn’t want publicized, the columnists would be given a film for free for some charity show they were involved in. A couple of contractees would also be asked to attend and provide some star power. Between pleasing the studio and pleasing Hedda or Louella, it was a twofer.

Looking back, it was clearly a culture of back-scratching.

Hopper did have her pet hates, which she vented about often enough. She was particularly venomous about Charlie Chaplin’s politics and bent for young girls, but Chaplin was an independent who prided himself on his independence, and didn’t have the protection of a studio. If he had been under contract to a major studio, I can assure you Hopper would have criticized him in a more muted fashion.

But with the mid-1950s came the rise of magazines like

Confidential

, which the studios couldn’t control. On top of that, the business was becoming decentralized, with the studios themselves now less important than the stars—a complete reversal of what Hollywood had been only twenty years before.

The rise of scandal sheets like

Confidential

meant that the studios had to learn to play defense. When

Confidential

was going to print a story about Rock Hudson’s homosexuality, Rock’s agent, Henry Willson, gave them Rory Calhoun instead—Calhoun had been busted for robbery as a juvenile—to protect Hudson, a far more important client. Most people thought that it had been Universal, the studio where both actors worked, who’d acted in this craven manner, but the culprit was even closer.

It was a simple calculation on Willson’s part—10 percent of Rock’s salary meant a lot more than 10 percent of Calhoun’s.

Ultimately, it didn’t make much difference. Willson, who was not only grossly unethical but unsavory as well, died broke. The relevant point here is that, twenty years earlier, or even ten, nobody would have dared print the truth about either actor.

While the monopoly that Jack Warner, Louis B. Mayer, and the rest of the founding moguls had enjoyed was disappearing, television was making serious inroads into movie attendance. This meant that fewer movies were being made, which in turn meant that the rosters of actors, writers, and directors under studio contracts were severely pared. More people began operating as freelancers, losing the protection of the studio as they did so. When both stars and studios lost control over publicity, they quickly discovered that power could disappear very quickly.

In the 1960s Kodak introduced the Instamatic, a light camera that fit in a pocket and used film cartridges that could be quickly switched, making picture taking easier than it had ever been before. I remember talking to Cary Grant once about the proliferation of new cameras, and he paused and said, “That’s the end of celebrities.”

He was speaking about a celebrity’s loss of control of his or her own image. And he was right, although that loss involved a lot more than just the Instamatic.

The transition from an orderly process regarding publicity to the law of the jungle became obvious with Richard Burton, Elizabeth Taylor, and

Cleopatra

. I was in Rome when that film was being shot there, and that’s all anybody talked about. Along the Via Veneto, the paparazzi

ignited

. And suddenly the paparazzi mattered more than they ever had, because for the first time there was real money at stake for the right picture of the illicit lovers together. That was the beginning.

Fifty years later, there are more stars than there used to be. Besides TV, there’s cable, and then there are celebrities who don’t do anything but be famous—the Kardashian sisters are the new Gabor sisters, but less amusing. There are also far more outlets for photographs of celebrities than there used to be, as the Internet has spawned countless gossip sites and blogs.

The shift in attitude is stunning. People used to be happy to see celebrities if they encountered them in public, and they were correspondingly pleasant. Going out to shop or get a meal was not a grueling run of the gauntlet. Very few photographers were allowed into the dining areas of restaurants or into hotels; unless a fan magazine set up a layout in advance at the Beverly Hills Hotel, you were in a zone of privacy.

Now photographers are looking for any opportunity to bust somebody, because that picture is worth so much. They’re desperate to get shots of people drunk or angry, so they bait them, trying to provoke an incident. In so many ways it has become a culture of violation. It’s true not just in show business, but in everything. If you’re in politics, you’re fair game as well.

A year or so ago Jodie Foster wrote an article whose central point was that, if she were a kid starting in the movie business today, she’d get out. According to her, it’s just not worth it. I’ve begun to think that maybe she’s right. If I were a young man today, I might just follow my father into business, and not the movie business.

I think that this adversarial relationship—the way that cameras shadow you every time you leave your house—is why a lot of celebrities have gotten out of Hollywood. George Clooney spends a great deal of his time in Italy; Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie go to New Orleans or a château in France. There, the media are less viperous, and the celebrities have a greater ability to move around.

It’s something I know all about. It’s even worse when tragedy strikes.