You Must Remember This (27 page)

Read You Must Remember This Online

Authors: Robert J. Wagner

Red Skelton mugs it up while Spencer Tracy carves a Thanksgiving turkey for the soldiers at the Hollywood Canteen.

Everett Collection

In other areas patriotism stopped at the studio door. The war years meant many sacrifices for the rest of the country, but they were comfortable for Hollywood. Although “rationing” became one of the keywords of the war, when it came to the stars and the people who presented them, those restrictions didn’t apply. Within the studios you could get nylons, gas, filet mignons, and other goods that the rest of America could only dream about.

Movie attendance during this era exploded, reaching as high as 90 million people a week—this in a country whose total population was about 135 million. Everyone was going to the movies.

Bette Davis serving cigarettes to the boys.

Everett Collection

After the war, the Hollywood social scene slowly began to change, although many nightclubs remained on and around the Sunset Strip. Ciro’s, Billy Wilkerson’s other great success, was still

a place to go in the 1950s. It opened at 8433 Sunset, the heart of the Strip, at the end of January 1940 and immediately became a magnet for stars and heavyweights in the industry. As always, Wilkerson gave his nightclub a luxurious setting befitting a Hollywood movie. The walls were draped in ribbed silk dyed a pale green, and the ceiling was painted the muted red of an American Beauty rose. There were sofas along the walls, with silk coverings dyed to match the ceiling. The lighting fixtures were custom made in the shape of bronze columns and urns.

Ciro’s was less of a spectacular dining experience than it was a place to be seen, and it remained that way for the duration of its existence. Billy Wilkerson wasn’t there very long; he had a low threshold of boredom and bailed out after a couple of years, but Ciro’s lived on. It was at Ciro’s that I saw Kay Thompson and the Williams Brothers—the best nightclub act I have ever seen in my life. Andy Williams was more than good by himself, but with his brothers, Dick, Bob, and Don, he was great. I miss Andy—he was a good friend.

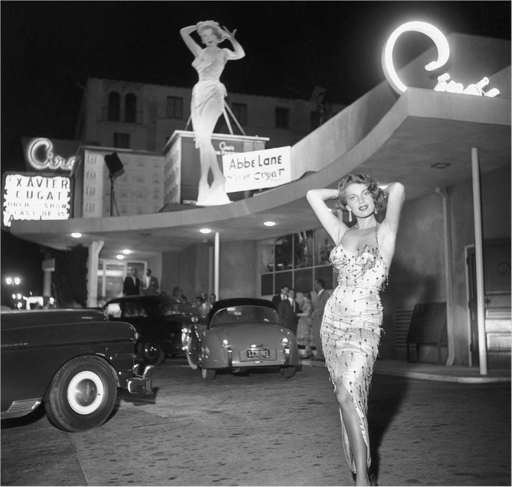

Abbe Lane outside of Ciro’s nightclub.

Michael Ochs Archives/CORBIS

In that era most nightclub acts were basically static; the performer stood at the microphone or sat at the piano, and that was that. But Kay and the Williams Brothers were in constant motion, which was made possible by a series of overhead microphones. Their chemistry was palpable, and the act was precisely staged and choreographed by Robert Alton, who had worked with Thompson at MGM.

Then there was the Mocambo, which was a few doors down from the Trocadero on the Sunset Strip. The Trocadero had a great view of the lowlying area south of the Strip, but the Mocambo, which opened at 8588 Sunset on January 3, 1941, had that and a little bit extra besides. Its décor was commonly described as a cross between a somewhat decadent Imperial Rome, Salvador Dalí, and a birdcage.

The swanky Mocambo nightclub on the Sunset Strip in June 1951. The table in the center hosts a dinner party thrown by gossip columnist Louella Parsons.

Getty Images

The color scheme was soft blue, terra-cotta, and silver, and along the walls were paintings by Jane Berlandina, as well as huge tin flowers. The columns were a flaming red—that sounds like Dalí—covered with paintings of harlequins. As for the birdcage, that referred to a long glass aviary that was alive with dozens of brilliantly colored parrots and macaws. To my knowledge, it was the only public aviary in Los Angeles, and it attracted a lot of attention, although initially local animal lovers petitioned to have the birds protected from all the nightclub noise. Charlie Morrison, one of the owners, agreed to install thick curtains around the aviary during the day so the birds could get some rest. The Mocambo, along with Ciro’s, was one of the premier nightspots for twenty years—a very long run in a transient business.

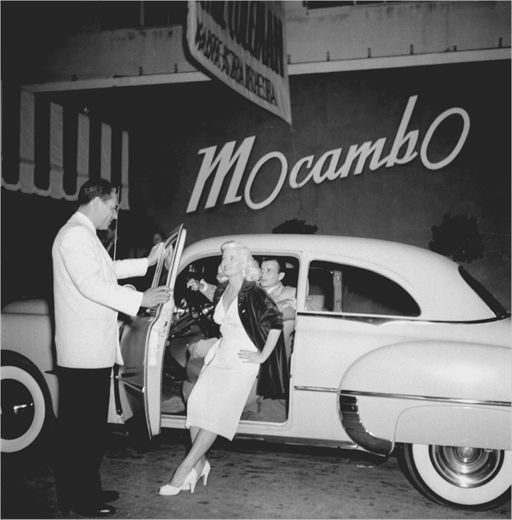

A pretty girl excited for a fun night at the Mocambo.

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

In all the first-class Sunset Boulevard nightclubs, jackets and ties were required for the men, and slacks weren’t allowed for women. Likewise, unescorted men and women were discouraged, probably to minimize the presence of hustlers. Which is not to say that nothing untoward went on. A lot of women would arrive with a bevy of male escorts, and often one man would enter with several women. They would then split up, and it was every man and woman for him-or herself.

The Mocambo had a bandleader named Emil, who would

always strike up “That Old Black Magic” whenever Bogart and Bacall walked in. Interestingly these clubs were integrated long before the rest of America, at least as far as the entertainment went. Hazel Scott played the Mocambo for years, as did the Nat King Cole Trio.

The heyday of the Trocadero—at 8610 Sunset or, as Billy Wilkerson’s ads had it, “Boulevard de Sunset”—was in the thirties and forties. When I started going there in the 1950s, it was still a special place, as were all of the fabled clubs on that part of the strip.

Certainly, it was full of special people. Everybody went to the Troc, from moguls like Sam Goldwyn and his wife, to the invariably unattached Joe Schenck, to directors like William Wellman and stars like Bing Crosby and William Powell. Marlene Dietrich was a regular, as was Louis B. Mayer, who liked to go dancing there in the interim between divorcing his first wife—a pleasant, slightly dull woman he had married in Boston decades before—and marrying his second—the glamorous widow of a William Morris agent.

The Troc was one of the few clubs where Fred Astaire would be seen. Fred didn’t go out much, because his wife Phyllis was shy and didn’t like what Satchel Paige referred to as “the social ramble.” Since Fred adored Phyllis, he was perfectly happy to stay close to home. Avoiding nightclubs was also a good way of avoiding the women who would beg Fred to dance with them. Just as mail carriers aren’t enthusiastic about taking walks on their days off, Fred didn’t particularly care for social dancing.

The Trocadero certainly didn’t look like much from the outside, but Harold Grieve successfully converted the interior into a stylish French café, and in keeping with the décor, the menu was French as well.

The walls were painted cream, and there was a touch of gold in the molding and the striped silk chairs. Many people in the industry believed that the Troc kicked off Hollywood’s great period of off-screen glamour.

A rare shot of Mr. and Mrs. Astaire, photographed along with Robert Montgomery, during an evening meal at the Trocadero.

Bettman/CORBIS

I remember that one of the highlights of the place was a wall-size mural of Paris as glimpsed from the Sacré-Coeur. In front of the mural there was a real railing on which rested a pot of fresh flowers. The illusion, especially in dim light, was quite lovely.

The Trocadero was expensive—drinks began at sixty cents and went all the way up to a dollar fifty for something called the French 75 (which sounds like a condom). The house special was the Trocadero Cooler, which cost seventy-five cents. (For context, two filet mignons at the Cocoanut Grove would set you back $14.50 in 1937 dollars, or not much less than the average weekly paycheck.)

Billy Wilkerson had a showman’s knack for innovation. Sundays were traditionally a dead night in the nightclub business in

Hollywood, because people had to be at work early on Monday morning. So Billy started what amounted to an open-mike night, where young talent could perform. The result was that Sunday night at the Troc ultimately became nearly as popular as Saturday, as movers and shakers began to feel obliged to attend, lest some other studio sign a brilliant young comic or dancer.

The Trocadero was enormously influential, and other clubs tried to get in on its success by opening on or around Sunset Boulevard. At the height of the Sunset Strip—just before, during, and after World War II—Mocambo, the Trocadero, La Rue, and the Crillon were all within a few blocks of one another; if you went to one, chances are you’d go to a couple of others for a drink or a nightcap.