You Must Remember This (28 page)

Read You Must Remember This Online

Authors: Robert J. Wagner

Although they presented some of the same acts, these clubs were not really analogous to the nightclub culture of New York City. They had a different clientele, and I found them more personalized than the clubs of New York. Mainly, they seemed less formal. On the Strip you could just drop in after dinner to catch a wonderful act; most of the places had a cover charge, but it was often waived for celebrities.

There were, of course, clubs that offered more than a meal and conventional entertainment. On Harold Way was a place called Club Mont-Aire, which offered pleasures of the fleshly variety. Several doors away from the Mont-Aire was a house run by one of Hollywood’s legendary madams, a lady—I have been assured by several of her loyal customers that she was, in fact, a lady—named Brenda Allen, whose outfit was finally closed down by the vice squad in 1948.

Radio had become increasingly important to the local economy in the early 1930s, and both NBC and CBS built large radio studios within a few hundred yards of each other. NBC was

at the intersection of Sunset and Vine, and CBS was on Sunset east of Vine.

The hundreds of people who worked for the two companies meant that there was a surge of restaurants around the area. The Brown Derby was already there, but it wasn’t long before it was joined by Sardi’s, the Coco Tree Café, Mike Lyman’s, La Conga, and a couple of fast-food drive-ins.

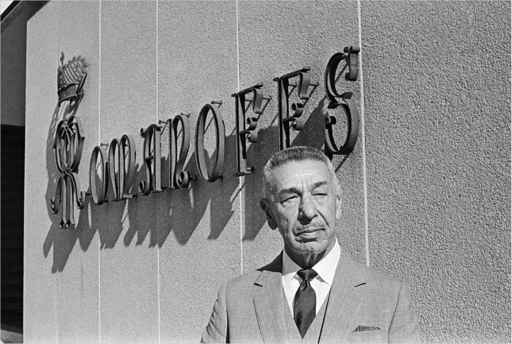

Of all the restaurants that opened around World War II, I remember Romanoff’s most fondly. It was run, of course, by the man who called himself Prince Michael Romanoff. Everybody knew that he wasn’t really “a cousin of the late Czar,” as he liked to proclaim (though not too insistently), but nobody seemed too sure about who he really was. Apparently Mike Romanoff was actually Harry Gerguson, the son of a Cincinnati tailor, although the mystery of his origins persists to this day. In any other town but Hollywood, that sort of impersonation would be considered reprehensible, if not actionable, but in Hollywood it’s called . . .

acting

.

Mike was such a charismatic man! The story went that he enlisted Harry Crocker, a very well-connected friend of Charlie Chaplin’s and a columnist for the Hearst papers, to finagle seventy-five hundred dollars each from a bunch of movie people as seed money for a restaurant. Among the investors were Robert Benchley, Cary Grant, Darryl Zanuck, and John Hay Whitney, the latter of whom had also bankrolled Selznick International. Supposedly, Jack Warner also put up some money, and Jack and Darryl were not exactly bosom buddies.

By the time I met Mike in the late 1940s, he was a prince of the realm—impeccably trimmed mustache, with spats and a cane. He lived in hotels, he borrowed money from everybody, usually paid it back, and was incredibly charming. Despite his name, he didn’t attempt a fake Russian accent but actually spoke in a vague mid-Atlantic one that might have been an attempt at stage British. As a nobleman, Mike was a total fraud, but he acted as if he believed it. We all played along.

Mike Romanoff in front of his eponymous restaurant.

Bettmann/CORBIS

Mike opened Romanoff’s in 1941, at North Rodeo Drive, and by 1945

Life

magazine had called him “the most wonderful liar in 20th-century U.S.” Someone else would have sued, but Mike just smiled, and the customers kept coming, so much so that in 1951 he had to move to larger quarters at 240 South Rodeo Drive.

For Romanoff’s décor Mike put on the imperial pretensions befitting a man known to his friends as “The Emperor.” The place had a roof garden, a ballroom, a small private dining room, and the large dining room, which held twenty-four booths. The wallpaper was orange, green, and yellow. There were no secluded corners, and

the entry had a short flight of stairs, situated so that everybody in the dining room could see who was coming in. Or, to put it another way, everybody coming into the dining room could make an entrance.

As you walked in, the first seven booths on the left were reserved. One was for the proprietor, who also favored his own food but seemed to prefer to eat alone, accompanied only by his two large dogs, Socrates and Confucius, whom I recall as being large bulldogs.

If Mike liked you, or if you were a regular, you could hang around as long as you wanted. You could play gin rummy, some backgammon, or just talk. Mike put a premium on familiar faces, and if he didn’t like you or if you were unfamiliar, you didn’t have to do much to get kicked out. The place of honor was usually occupied by Humphrey Bogart—second booth on the left, as marked by a plaque, which also carried the names of Robert Benchley, Herbert Marshall, Sir Cedric Hardwicke, and a few others who were allowed to use it. Other Romanoff regulars were Jack Benny, Frank Sinatra, and Gary Cooper. Dinner regulars were Louis B. Mayer, Darryl Zanuck, and Harry Cohn.

Frank Sinatra was one of Romanoff’s biggest fans—Frank liked to eat, and he had very good taste in food. The problem was that all those years of singing in nightclubs meant that Frank liked to eat at odd hours. He couldn’t sing on a full stomach, so he got used to dining after his shows, very late at night. This would have been awkward for other people, except that other people tended to calibrate their clocks around Frank. When he was in the mood, Frank was also an excellent cook—mostly Italian. Frank would cook fine meals for special friends, and I had a lot of meals at his house with Spencer Tracy.

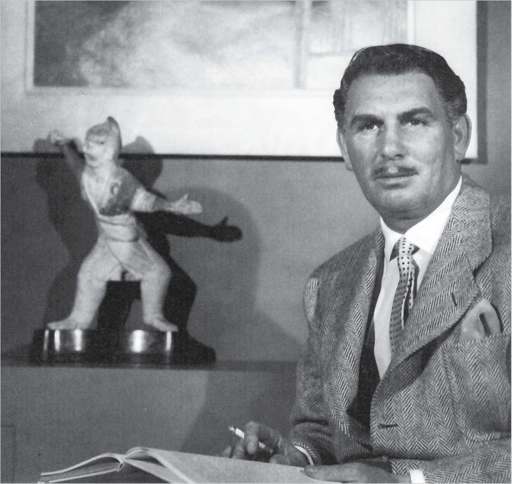

Another Romanoff’s regular was Charles Feldman. Hollywood was the home of great characters, and I don’t mean great character actors. I mean people who really made the town work but who were not public in any sense—people who preferred to work quietly, out of the eye of publicity.

Dean Martin, Prince Mike Romanoff, and Frank Sinatra having a good time.

Bettmann/CORBIS

Agents, for example.

The cliché image of agents as cigar-chomping clods has an element of truth to it, but the broader truth was considerably more varied. Charles Feldman, known as the Jewish Clark Gable because he had the same hairstyle and mustache as Clark, happened to be my own agent. He was an elegant, dapper, unruffled man who always gave the impression that he had the upper hand in whatever negotiation he was engaged in—because he always did have the upper hand. He was also a gentleman who was reputed to have never won a game of gin yet never complained when he lost. A lot of Charlie’s business was done over a table at Romanoff’s. That way, even if the deal didn’t work out, he was at least assured of a good meal.

The legendary Hollywood agent Charles Feldman.

Courtesy of Cathy Phillips

Feldman was a hugely influential man in the history of Hollywood, but also one who has been underappreciated, because he preferred to work behind the scenes. I believe that Charlie invented what came to be known as the package deal. In the mid-thirties he realized that the problem with agenting was that you were effectively like a child raising its hand hoping that the teacher—the studio head—would call on you and hire your client. The balance of power was tipped entirely to the side of the studio head.

Feldman reasoned that the agents had to create some leverage for themselves, which he did by creating jobs for clients. He would

take one of his own writers and have him develop either an original or adapted screenplay, for which Charlie would front the money himself. He would then cast the project with a couple of his own actors and finish off the package with one of his own directors. He would present the entire package to a studio, which could buy it at a hefty profit for Charlie but for less than it would have cost the studio to produce it themselves if it had to hire all the talents individually.

Because this took most of the work off the backs of the studios and the resulting picture would represent something of a bargain, a lot of studios went for the deal. And since Charlie had a premier group of clients—including John Wayne, Howard Hawks, Irene Dunne, Marlene Dietrich, and so forth—he could mix and match them in various enticing combinations. It was Charlie who put together

Red River

with Hawks and Wayne, for instance, although his name never appeared on the screen. The screenwriters for that independently made picture were also his clients, and Charlie even helped round up the money for it. Ditto

A Streetcar Named Desire

, although he took a producer’s credit on that one.

By the time Charlie sold his agency in 1962, he was grossing around twelve million dollars a year. He produced a few more pictures and died, far too young, in 1968.

Charlie and the rest of the town liked Romanoff’s because the food was special, often excellent. Mike flew in sole, and I remember an excellent charcoal-broiled steak for two, which was sliced and came with a very fine mustard sauce.

Mike specialized in French cuisine—he prepared a wonderful bouillabaisse, and a saddle of lamb as well. I also remember the steak tartare, the cracked crab, and the wonderful vegetables. Dessert was not for the faint of heart, or for anybody whose belt was on its first hole: cherries

jubilee, crêpes suzette, and the house specialty: individual chocolate soufflés. Mike’s banana shortcake was famous, and it deserved to be.

Mike was a great bon vivant. He always called me “The Cad,” which has kept me laughing for more than sixty years. Mike’s only real problem was that the expansion to South Rodeo became a challenge. The restaurant was simply too big—a lot of the time it looked underpopulated. Another problem was that Hollywood was, and is, always in flux—new people are always displacing the old, and those new folks want places of their own.

Romanoff’s began to seem slightly old and musty, and Mike only made things worse by allowing his politics a place in the restaurant, actually distributing Republican campaign literature to his patrons. I don’t care what your politics are, no one wants to be harangued over a meal.

The final nail in the coffin came when Mike opened a satellite restaurant in Palm Springs, ominously called Romanoff’s on the Rocks. I was there for the opening of the new venture, along with Frank Sinatra and Jimmy Van Heusen, the songwriter whose real name was Chester Babcock and who was Frank’s role model. Jimmy was a total original and an extremely funny man. He once called a bunch of apartments in a New York skyscraper and asked them to all put their lights on at an appointed hour. When they did, the name “JIMMY” was spelled out. Like I said, an original.