You Must Remember This (12 page)

Read You Must Remember This Online

Authors: Robert J. Wagner

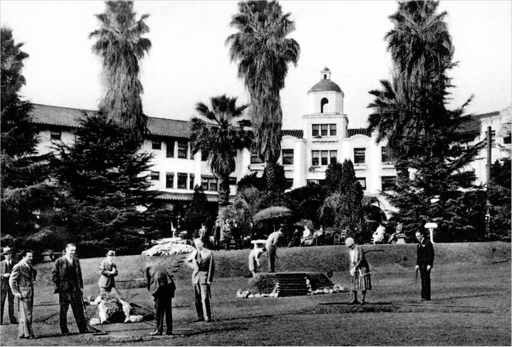

Harold Lloyd in the garden of Greenacres, his palatial Spanish-style villa in Beverly Hills.

Getty Images

All the furniture in the house was custom made, but Harold was from a small town in Nebraska and, believe it or not, was far from a spendthrift. Harold had a sunroom that had trompe l’oeil vines painted on the walls. The painter did a great job on the vines, and they looked quite lifelike. But he was very slow, and after a year or two the vines were still in progress. One day Harold had had enough and he told the painter he had exactly three weeks to finish the job. This explains why the small, carefully painted leaves suddenly got about five times as large in one corner of the room.

Me with Harold Lloyd’s daughter Gloria, at a costume party at Harold’s Palm Springs home.

Courtesy of the author

I met Harold Lloyd around 1948, when I began dating his daughter Gloria. Harold approved of the potential match, and I have to admit that his approval meant a great deal to me. At that point, Greenacres was only slightly more than twenty years old, but the upkeep on the place was huge, and Harold was no longer making a million dollars a year. He was economizing. The house had never been redecorated—the drapes were getting ragged, the furniture was frayed. Nothing had been replaced.

One year he got too busy to take down the Christmas tree, so there it stayed. Finally, he made up his mind to have a Christmas tree all year round, so each year he would install and structurally reinforce a fifteen-foot-tall tree, and then take two weeks to hang a

thousand ornaments out of the ten thousand he owned. It was beautiful and eccentric—but mostly beautiful. I’m very proud that one of the ornaments on the tree was a gift from me. I also had an autographed picture in what Harold called his Rogues’ Gallery, a subterranean hallway lined with signed photos from everybody from Chaplin to DeMille.

Harold’s famous Christmas tree. I’m proud to say that somewhere in there is the ornament I gave him.

Harold was one of those men who had to be busy all the time. In most respects, he was a sweet man. He was passionate about photography, passionate about the movie business. Like Fairbanks and Chaplin, Harold owned his own films, which was highly unusual for the period . . . or for any period, come to think of it.

Harold’s retirement was more or less enforced by a cumulative lack of success in talking pictures, and it must have been difficult for him. He channeled all his energy into hobbies, but the problem with hobbies is that they’re more about filling time than producing something that will stand through time—as Harold’s films have.

But Harold kept busy. He collected old cars. He prided himself on his stereo system—the living room featured thirty-six speakers when he really cranked it up gold leaf would drift down from the ceiling like snow. Harold also became fascinated by the theory of color and started painting, and he even took up 3D photography. He ended up with more than six thousand 3D photographs. He was, in short, very interested in life. He was loyal to his staff; there were a few people he kept on salary that had been with him since the 1920s.

But in some respects, Greenacres was a strange house. Harold was consumed by his hobbies . . . and by young women. Everybody else was left to more or less fend for themselves. Mildred Davis, his wife, quietly drank. His son Harold Jr. was gay, and had a strained relationship with his father. It was a huge place for only five people,

and it would have been possible to go for days without seeing anybody.

Harold died in 1971, but I retain a soft spot for both him and his unparalleled home; I shot episodes of

Switch

and

Hart to Hart

there—my way of staying in touch with my old friend. Harold’s granddaughter Suzanne has shepherded Harold’s movies—the most valuable part of her inheritance—with great diligence and care, so that future generations will always be able to appreciate what a great comedian and producer Harold was.

Harold, his family, and Greenacres will always be in my heart.

By the time I started going to the Beverly Hills Hotel in the late 1940s, there were already legends about the place, and there would be more in the future. Here are some that I know to be true:

Will Rogers and Spencer Tracy did play polo in what used to be a bean field behind the Polo Lounge. Clark Gable and Carole Lombard did have trysts there while waiting for his divorce to become final. “We used to go through the God-damnedest routine you ever heard of,” Lombard recalled. “He’d get somebody to go hire a room or a bungalow somewhere. . . . A couple of times the Beverly Hills Hotel. . . . Then somebody would give him a key. Then he’d have another key made, and give it to me. . . . Then all the shades down and all the doors and windows locked and the phones shut off. . . . But would you believe it? After we were married, we couldn’t ever make it unless we went somewhere and locked all the doors and put down all the window shades and shut off all the phones.”

That was Garson Kanin reporting what Lombard had told him, and I think it’s accurate until the end, when she claims that Gable had performance anxiety unless the place was locked down tight. I knew Clark, and I can assure you that, while he would have made sure the door was locked, that would have been the extent of his paranoia.

The pool at the Beverly Hills Hotel.

Photofest

Guests playing mini-golf on the grounds of the Beverly Hills Hotel.

Photofest

In other romances, Marilyn Monroe and Yves Montand did carry on their affair in bungalows 20 and 21 while making

Let’s Make Love

, and Elizabeth Taylor did spend several of her honeymoons in the bungalows.

Howard Hughes kept three bungalows rented at a time. For around thirty years beginning in 1942, Bungalow 4, which had four rooms, was for Hughes’s personal residence. Bungalow 19, which he kept for Jean Peters, his wife, had three rooms. (It should be mentioned that Bungalows 4 and 19 were far apart.) Bungalow 1C was for his bodyguards.

There were times when Hughes would have as many as nine of the bungalows rented, a couple of which would be occupied by girls he had signed for RKO. The rest would be empty.

He also would occasionally book the Crystal Room on thirty minutes’ notice. The Crystal Room held a thousand people, but Hughes’s meetings usually involved only four. Once, Hughes’s Cadillac was parked at the hotel for two years without ever being moved. The tires all gradually flattened, but nobody inflated them and nobody moved the car.

Were any average hotel guest to leave his Cadillac on the grounds to deteriorate, the car would be towed and the owner would be presented with the bill. But Hughes was too good a customer for the hotel to take any such drastic measures.

By 1948, Hughes’s injuries from his Beverly Hills plane crash were beginning to overwhelm him. He would stay inside Bungalow 4 for months at a time. I remember the staff at the hotel mulling over Hughes’s eccentricities—the way he would order roast beef sandwiches (the hotel went so far as to designate a “roast beef man,” who was the only one who had been able to master Hughes’s careful instructions about how to prepare them) accompanied by pineapple upside-down cake. He would tell the staff to stick the sandwiches

in a tree, then retrieve them when nobody was around, so no one would know in which bungalow he was staying. He also liked Hershey chocolate bars and Poland Spring water.

In 1949 John Steinbeck met his last wife at the Beverly Hills Hotel. He was in town working on

Viva Zapata!

and a friend offered to fix him up with Ava Gardner. Gardner wasn’t interested, so the friend fixed him up with Ann Sothern instead. They hit it off, and he invited her to visit him in Monterey. She brought along a friend named Elaine Scott, who was married to Zachary Scott. But not for long—Steinbeck and Elaine hit it off to such an extent that both Ann Sothern and Zachary Scott faded into the distance. Supposedly Sothern never forgave Steinbeck . . . and quite probably never forgave Elaine Steinbeck, either.

Other bungalows had other famous guests. Bungalow 5 was the favorite of Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, and Paul and Linda McCartney liked it as well. Bungalow 9 was the home of Jennifer Jones and Norton Simon for five years. Bungalow 11 sheltered Marlene Dietrich for three years, including her custom-made seven-by-eight-foot bed. Bungalows 14 to 21 were known as “Bachelors Row,” and were the favorites of Warren Beatty and Orson Welles among many others.

By the 1950s, the Beverly Hills Hotel was synonymous with Beverly Hills itself. But in fact, in 1933 the hotel had closed because of the Depression and stood vacant for two years, until the Bank of America reopened it a year later.

In 1942 the hotel was purchased by Hernando Courtright, who was a vice president at the Bank of America. He had no experience in the hotel business, but he knew a good opportunity when he saw one, so he raised one hundred thousand dollars from Harry Warner, Irene Dunne, and Loretta Young

*

—notice the pedigrees. Then he borrowed another seventy-five thousand dollars to remodel the place.