You Must Remember This (15 page)

Read You Must Remember This Online

Authors: Robert J. Wagner

All this was too much for Rogers. He sold his house on North Beverly Drive and bought a ranch that encompassed several hundred acres at the far reaches of Sunset Boulevard in Pacific Palisades, where he lived for the rest of his life, and where he built one of the finest polo fields in the West.

Years later, I would buy a place of my own just around the corner from Rogers’s ranch, which by then was the Will Rogers State Park. I lived there with my daughters and Jill for more than twenty years, and that land was a great healing force for me, just as it had been for Will Rogers.

When Rogers bought his property, he was pretty much alone out in Pacific Palisades, which was just the way he liked it, if only because it was a long drive to the studios, which were in Hollywood (Paramount, RKO, Columbia) or the San Fernando Valley (Warner Bros.).

Because of proximity to their workplace, a lot of the people at Warner bought places near Burbank and North Hollywood. Bette Davis bought a two-story redbrick Tudor house behind a wall in Glendale, which was only about ten minutes from the studio. This meant she could sleep for an extra hour in the morning—no small

thing when you have to be on the set, in wardrobe and makeup, by eight a.m.

Relatively rural places like Sherman Oaks, Encino, and Tarzana were mostly barley fields and orange groves, with a smattering of chicken ranches, until the 1950s. For those who liked country living, these were choice locations. Clark Gable and Carole Lombard had a thirty-two-acre ranch in Encino, fronted by a white brick and frame colonial. It was all very homey, with early American furniture and a room set aside for Clark’s collection of rifles—he was an excellent skeet and bird shooter.

By the late 1930s and 1940s, a lot of incredibly opulent houses had begun to be built in Bel Air and, just outside its limits, in Holmby Hills. One of the first stars to move to Holmby Hills was Jean Harlow. Her Georgian mansion was all crème and gilt, and it was also huge—but then, her mother and her mother’s husband also lived with her. William Powell, with whom Harlow had the last serious relationship of her life, thought the house was ridiculous and her relationship with her mother destructive; he urged her to get rid of the place and save some money before her mother drove her into bankruptcy. She followed his advice and rented a much cheaper house, but she died before she was able to put down any roots.

Without question the most opulent house I have ever been in was Jack Warner’s.

It was an immense Georgian mansion, more than thirteen thousand square feet, sitting on nine acres of property. It had two guesthouses, terraces and gardens, three—count ’em,

three

—hothouses, a nursery, and a nine-hole golf course. Harold Lloyd, Jack’s next-door neighbor, also had a short nine-hole golf course on his

property, and Jack built a bridge between the two properties so guests could play eighteen if they so desired.

The interesting thing about Jack’s estate—“house” doesn’t begin to cover it—was that Jack put it together piece by piece over a ten-year period. He originally bought three acres in 1926 and built a fifteen-room Spanish mansion. But three acres felt insufficient, so Jack added another parcel of land, and then another.

The grounds were completed in 1937, at which point Jack turned his attention to his house. He hired Roland Coate to enlarge and completely redesign the old Spanish mansion into a new Georgian mansion, and Coate went to town on the assignment.

When he was done, besides the house itself and the guesthouses, there were gas pumps and a garage where repairs could be done on Jack’s fleet of cars. But everybody agreed that the pièce de résistance was the golf course. The holes were on the short side—pitch and putt, really—but that wasn’t the point. The point was that Jack had enough power and money to customize a golf course on some of the most valuable real estate in the world.

If you didn’t already know that Jack was a rich and powerful man, the entrance to his mansion would have told you. Past the iron gates was a winding driveway lined by sycamores. You ended up at a brick-paved motor court by the portico—all white and classical. Across the way was a fountain, and beyond that were landscaped terraces decorated with statues and urns.

Needless to say, the interior of the mansion maintained the same impression of grandeur. Jack hired William Haines to do the decoration. Haines liked big houses.

Billy filled the house with antiques befitting the setting—authentic George III mahogany armchairs, writing desks,

eighteenth-century Chinese wallpaper panels. (At this stage of his career, Haines liked French and English antiques with chinoiserie accents—a weird kind of Regency effect. In later years, he modernized his style to something more aerodynamic and Scandinavian looking.)

The front door opened into a two-story hall with a parquet floor. Sweeping up the side was a curving cantilevered staircase. On the wall as you ascended the staircase were paintings by Arcimboldo, the eccentric artist—well,

I’ve

always thought he was eccentric—who made portraits out of fruit and vegetables.

The library was where Jack spent the most time, because it had been converted into a screening room where he watched movies with his executives. When you twisted the head of a Buddha, paintings would rise and a screen would emerge.

The library, which also held a collection of scripts from Warner Bros. films, was largely decorated in orange, from the couches to the curtains. Because of the color scheme and the low furniture—so heads wouldn’t get in the way of the projector’s beam—it had a more modern feel than the rest of the house, except for some Louis XV–style panels that broke up the walls and drapes.

Somewhere in the house over a mantel, I recall a portrait of Ann Warner painted by Salvador Dalí. The bar had a large wooden floor and more orange accents, with Tang dynasty pottery and a couple of huge candlesticks that I seem to recall came from a Mexican cathedral. Behind the bar were statues of the Buddhist deity Guanyin, which Ann had insisted reappear in various places throughout the house.

I always wanted to ask Jack what he thought about Buddhism. Maybe he figured a little Buddhism on the side amounted to

hedging his bets, but the truth is I don’t think Jack Warner ever believed in anything except Jack Warner.

Overall, the house was more like an architectural museum than a place you’d actually want to live. When you had the privilege of dining at Jack’s house, the silverware wasn’t silver but gold, and a footman stood behind every diner at the table.

Ann Warner was a very upbeat lady, vivacious and full of life, even though theirs was a difficult marriage. In the silent days, she and Jack had had an affair, which eventually resulted in his divorcing his first wife and her divorcing her husband Don Alvarado, one of the many actors who vied for Rudolph Valentino’s public after Valentino died. (To give you some idea of the incestuous nature of Hollywood, Don Alvarado later went to work for Jack at Warner Bros., using the name Don Page.)

Ann had at least one other serious affair after that, with Eddie Albert. As for Jack, monogamy was not part of the marital deal as he understood it. Yet he was mortally afraid of his wife. I’ve never understood why, but there it is. Whatever their private compromises, they stayed married for the rest of their lives.

There was an intense clannishness on the part of the Warners. For that matter, that same clannishness played a part in the character of almost all the men who formed Hollywood. That, and an extreme competitiveness.

For instance: In the 1950s, Jack euchred his brother Harry out of the studio. Jack had suggested to Harry that they sell out and retire to enjoy their families and the fruits of their labors. TV had rolled in, the audience was declining, they were both getting older, and it wasn’t fun anymore. The argument was convincing, and Harry went along with it.

But Jack was bluffing—he had no intention of retiring. After their combined shares were sold to financier Serge Semenenko, Jack bought back all the shares in a prearranged sweetheart deal. (Semenenko had a coarseness all his own; my wife Natalie once told me that when she met Semenenko for the first time, he stuck his tongue down her throat. Even Jack wasn’t that crude.)

Warner Bros. was now the sole possession of Jack Warner. Harry had a stroke soon afterward and was never the same man. When Harry finally died, Jack didn’t go to the funeral, but then he probably would not have been welcome. Sixty-odd years later, Harry’s side of the family rarely, if ever, speaks to Jack’s side of the family.

Clan loyalty dies hard.

I played a lot of tennis at Jack’s house. The tennis court was professionally lit, so you could play at any hour of the night. He didn’t look like it, and God knows he didn’t act like it, but Jack was a very good tennis player, as was Solly Baiano, his executive in charge of talent. But you had to be wary of Jack on the court—his calls about a ball being in or out of bounds could be highly questionable.

Did Jack cheat? I wouldn’t put it like that. But I would say that his competitive nature led him to make consistently dubious decisions. Let’s just say that after playing tennis with Jack Warner, you had an increased respect for what Bette Davis, Errol Flynn, and Jimmy Cagney had to go through for all those years.

After Jack died in 1978, Ann stayed on at the house until her death in 1990. At that point, David Geffen purchased the estate and the furnishings for $47.5 million. Jack’s house was the last entirely intact estate to be sold in Beverly Hills, and the money Geffen paid set a national record for a single-family residence.

Geffen is a man of taste, so I’m sure he’s maintained it as Jack

and Ann would have wanted, but somehow I can’t imagine that house without those two around to liven it up.

In stark contrast to Jack’s house was that of Lew Wasserman, the head of MCA Universal. Lew was of a different generation than Jack and had very different politics—Lew was a Democrat, while Jack was a conservative Republican—so it’s not surprising that he had a very different temperament as well. If he liked you, he was warm and accommodating, but to those people toward whom he was indifferent, or simply in business with, Lew could be one cold fish.

Lew’s house was quite modern, and was an authentic reflection of his personality. It featured stark lines, but also art that he understood, including paintings by Vlaminck and lots of Impressionists. Lew would usually entertain at Chasen’s, but he would also occasionally invite guests to his home. In either case black tie was called for, because that’s the sort of couple that Lew and Edie Wasserman were.

Interestingly, the homes of the great movie moguls didn’t seem to have much direct relationship to their personalities as reflected in the movies they made. The contrast between Jack Warner’s house and Jack’s films, for example, was staggering. Warner Bros. movies typically featured snarling mugs like Cagney, Bogart, and Eddie Robinson and tough women like Bette Davis, but his home was the height of rarified style. If I had to take a guess, I would say that his movies represented Jack as he actually was—dapper, energetic, and cracking cheap jokes—and the house represented him as he wished to be.

Joe Schenck ran United Artists and was the chairman of 20th Century Fox. Yiddish has a word for Joe Schenck:

haimish

. Joe was a rabbi to everybody in the movie business. He was round, unassuming, unpretentious, and wise.

After Norma Talmadge divorced him because she was having an affair with Gilbert Roland (later, she would marry George Jessel—there’s no accounting for taste), Joe built a neoclassical mansion on South Carolwood Drive, just west of Beverly Hills. There he spent the rest of his life entertaining beautiful young women, including Marilyn Monroe. Joe died in 1961, and subsequent owners of the house included Tony Curtis and Sonny and Cher.

Darryl Zanuck, who gave me my career, built one of the last great homes to be constructed along the Santa Monica stretch of beach. Darryl’s movies were evenly divided between light entertainments in garish Technicolor (such as Betty Grable’s films), grim film noirs (

Nightmare Alley

,

Call Northside 777

), and westerns that could have been film noirs (

My Darling Clementine

,

The Ox-Bow Incident

). Darryl was always an innovator, a ceaselessly active man—I can barely remember him standing still

.

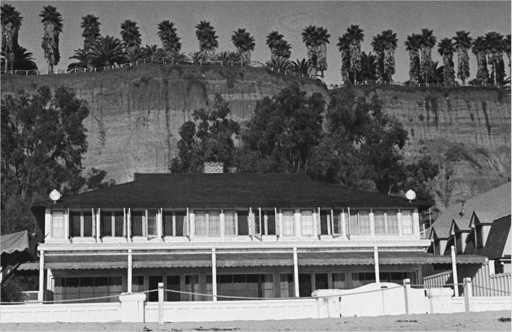

Darryl’s house at Santa Monica beach, 546 Ocean Front, was a three-story white clapboard house that could have been transplanted intact from New England or upstate New York. Darryl and his wife Virginia Fox hired Wallace Neff to design the house; when the job was finished in 1937, Virginia hired Cornelia Conger to do the interiors.

You would never know that it was the home of one of the most dynamic moguls of his time, for there was nothing theatrical about it. Virginia’s collection of Staffordshire dogs and English china was displayed over the fireplace, and the whole house had a restrained English feel to it. The furniture was Chippendale and Old English, the wallpapers were hand painted—Virginia had excellent, refined tastes.

I suppose you could characterize the style of the Santa Monica beach house as predominantly Virginia’s, but Ric-Su-Dar, Darryl’s other residence (which he named after his children, Richard, Susan, and Darrylin), in Palm Springs, was not really any more in keeping with his own personal style—which was, in a word, swashbuckling. Darryl was a man’s man, a ladies’ man, and extremely competitive at everything to which he turned his hand.