You Must Remember This (17 page)

Read You Must Remember This Online

Authors: Robert J. Wagner

Mary E. Nichols /

Architectural Digest

May 1987

Our bedroom on Old Oak Road.

Mary E. Nichols /

Architectural Digest

May 1987

The signature Cliff May bird tower at our house. He gave us six pairs of Slow Roller pigeons that gave us so much pleasure.

Mary E. Nichols /

Architectural Digest

May 1987

I was honored to buy a house that Cliff had designed for his own family. Architectural historians refer to it as Cliff May House #3, which was built in the late 1930s on Old Oak Road, right off Sunset Boulevard. Cliff and his family lived there for fourteen years; then, in 1949, he added another 3,200 square feet, very nearly doubling the size. After I bought it in 1982, Cliff remodeled it yet again for our family.

It’s a low, rambling house, a brilliant solution for fitting a horse ranch into what was a suburban lot. It had a shake roof and a stable on the property for the horses that he, my wife Jill, my daughter Natasha, and I loved to ride. Originally it had three bedrooms, a maid’s room, three patios, a stable, a tack room, and a paddock. Over the years both the house and the horse areas were enlarged. The remodels made it one of Cliff’s California ramblers; it ended up designed like a wagon wheel, with the central living space in the center and several corridors leading out from there to the bedrooms and offices.

In 1947, Elizabeth Gordon of

House Beautiful

called Cliff’s #3 “the most significant ranch house in America,” an honor I had no concept of when I bought the place. I just thought it was an ideal place to raise my kids after a terrible tragedy, and I was proved right.

We rode horses there; we had countless meals there; we healed there. Jill and I were married there; my daughters, Natasha and Kate, and my son, Peter Donen, were all married there. It holds a special place in all our memories and always will.

It was less than a mile off Sunset Boulevard, but it felt as if you were a million miles away from the hurly-burly of Hollywood. I lived in Cliff May House #3 very happily for twenty-five years. Cliff once told me that people who don’t live in ranch houses “don’t know how to live.”

There was an interesting way of determining social standing in the parties of that era. Contrary to cynical popular belief, if your box office popularity fell off, you weren’t suddenly dropped from A-list parties; once you were in the group, you were in the group. If you were coming off a long list of flops, you might not be seated at the A table, but you’d still be in the A group. In that respect, I don’t think the movie business is really much different from any other business.

The great hostesses of Hollywood were more domestic entrepreneurs than they were chefs. Very few of them would spend much time in the kitchen; most contented themselves with planning and executing their soirees, or perhaps making a special hors d’oeuvre that they knew they could do well.

But there were a few exceptions. Connie Wald, Jerry Wald’s wife, did most of the cooking for her parties herself, and Jerry took a lot of pride in his wife’s abilities in the kitchen. Jerry, of course, was a huge promoter, and had a great ability to put the pieces of projects together.

Jerry didn’t make great pictures, but rather commercial ones that were solid entertainment. He was supposedly Budd Schulberg’s inspiration for

What Makes Sammy Run?

, although that implies a guy with more hustle than talent, and I always found Jerry to be a genuine hands-on producer. Connie, who was always at his side, lived to a very ripe old age, and when she died in 2012 she left instructions that she didn’t want a funeral; instead, all the people who loved her were to have a great dinner—at Connie’s expense.

Another couple who were among the greatest party givers of

that period were Bill and Edie Goetz. After World War II, as a young producer Bill Goetz started a production company called International Pictures. A few years later, he merged International with Universal and became a wealthy man.

From the outside there was nothing special about the Goetzes’ house. It was two stories, was painted a light gray, and had a wrought-iron porte cochere—just another house in Holmby Hills with interiors by William Haines, one of dozens in the neighborhood.

It was only when you stepped inside the house that you realized you were someplace special, for the walls were covered with the most spectacular display of Impressionist art outside the Musée d’Orsay. Bill and Edie had one of the finest private art collections in America. That was why Edie always entertained at home—it gave guests a chance to appreciate the collection, and it gave her a chance to show it off. Bill and Edie’s attitude toward their extraordinary assemblage of art was low key. They weren’t so presumptuous as to offer a guided tour, but if you had half a brain you’d ask them about some of the paintings—and how they’d gotten their hands on them. They wanted to share their objects of beauty with people.

The living room alone featured Cézanne’s

La Maison du Pendu

, Bonnard’s

Portrait of a Young Woman

, Manet’s

Woman with Umbrella

, Renoir’s

Nature Morte, Fleurs et Fruits

and Picasso’s

Maternité

. A Degas bronze ballerina sat on a table. I remember touching its skirt with awe, and hoping nobody noticed me.

In the sitting room over the fireplace was Van Gogh’s

Étude à la Bougie

, and the dining room contained a Sheraton table and Georgian silver. The walls featured Degas’s

Two Dancers in Repose

and a Bonnard called

Le Dejeuner

. Another wall featured a Monet, a Sisley, and, if I remember correctly, a Toulouse-Lautrec, which were all mounted on a wall that rose to reveal the projection room that was a standard feature for producers of Bill’s stature.

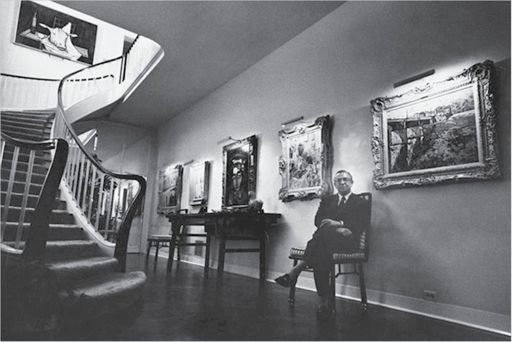

William Goetz seated with a portion of his art collection.

Courtesy of Victoria Shepherd—Bleeden

It was the screening room that drove people up the wall—to raise a Monet to watch a crappy movie, or even a good movie, struck some as the height of nouveau riche behavior. Irene Mayer Selznick, Edie’s sister, would tell everyone what poor taste she thought it reflected, even though the art itself was beyond reproach—well bought, and well displayed.

Edie and Irene were the daughters of Louis B. Mayer and they never really got along, mostly because they were extremely competitive. Each of them married an aspiring producer—Irene to David Selznick, Edie to Bill Goetz. David achieved greatness, Bill achieved success. There was, needless to say, a great deal of tsuris in the family, of jostling and unease.

Irene would eventually divorce David over his affair with Jennifer Jones, while Edie and Bill stayed married—quite happily, I believe. I met Irene only once or twice, just long enough to sense

how very different the sisters were. To put it in a nutshell, Irene was intellectual and Edie was social. Each of them understood the movie business backward and forward, although in different ways—Irene creatively, Edie in terms of politics and power.

I found Edie to be a very open person—if she liked you. If she didn’t, she simply didn’t bother with you. But it would be unfair to call her a snob; I always found her to be a gracious and generous woman, in attitude as well as spirit.

Frankly, with the art the Goetzes owned, the food and the company could have been drawn from Skid Row and it wouldn’t have diminished my appreciation. But Edie and Bill were strictly A-list—their guests were the Gary Coopers, the Jimmy Stewarts. Edie’s invitation would tell you whether the event was black tie or just to wear a business suit. The atmosphere was formal but not stiff. That is to say, if you knew Edie and the other guests, you’d be fine. If you didn’t, I imagine it would have been intimidating.

Edie’s staff was up to the standards of her guests. She always let it be known that her butler had once buttled for the Queen Mum at Buckingham Palace. Edie always had the finest of everything—food, wines, crystal, china.

Edie Goetz was

the

hostess of her generation—her only true competition was Rocky Cooper, Gary’s wife—and the women who came to Edie’s parties knew it. The women would trot out their best clothes, predominantly from couturiers. I remember a lot of Jimmy Galanos dresses, and I remember a lot of stunning jewelry—the real thing, not replicas.

Edie and Bill’s house was no place for false fronts. The paintings were real, the success of the guests was real, and so were the accoutrements of that success. The women wore their finest because they were part of an evening of special people, and they were proud to

show off their best. (In line with that, drinking was rarely a problem at A-list parties of this period. People were expected to know their limits and behave accordingly, and if they didn’t, they would very quietly be steered in a different direction or, in extreme cases, steered home. Unseemly behavior was rare.)

Bill Goetz was a funny, jolly man, with a deep, throaty voice like Ben Gazzara’s. He was a Democrat, although politics wasn’t what drove the wedge between him and his ardently Republican father-in-law. In 1952 Bill cosponsored a fund-raiser for Adlai Stevenson with Dore Schary, who had deposed Louis B. Mayer from MGM, the studio he had founded and that carried his name. Mayer begged his daughter to intervene and prevent what he felt to be further crushing humiliation at Schary’s hands, but she felt she had to remain loyal to her husband.

Mayer never forgave either of them. By the time he died five years later, he’d cut Edie and her children out of his will.

After that, the temperature between Irene and Edie never got much above freezing; it was the divided halves of the Warner family all over again. These men could forge empires, but the forging of functional families did not seem to be in their skill sets.

Bill Goetz died in 1969, and Edie hung on for nearly twenty years after that, although the parties gradually dried up. When Edie died in 1988, most of her estate consisted of the art collection on the walls. It was auctioned off for eighty million dollars—more than the estates of her father and sister combined.