You Must Remember This (16 page)

Read You Must Remember This Online

Authors: Robert J. Wagner

Darryl F. Zanuck’s Santa Monica beach house.

Time + Life Pictures/Getty Images

Darryl raised his family at the Santa Monica house, and some of his favorite employees were nearby—Ernst Lubitsch, for one, had a place a little farther down the Pacific Coast Highway. It was a perfect place for entertaining, and Virginia hosted many elegant Sunday afternoon buffets. She was a very gracious woman—that seems to have been a job requirement for the wives of the moguls—and I liked her tremendously.

The house at 546 Ocean Front clearly meant a lot to the Zanucks. Darryl’s son Richard—who used to be handed over to me to babysit, and who grew up to be a great producer in his own right—eventually bought the house from his mother and lived there for years with his own family.

Dick Zanuck was a remarkable man in so many ways—the obstacles he had to overcome in order to carve out his niche! He once told me the story of how he took over Fox. It was after

The Longest Day

, and the studio was in the doldrums. Dick went to Paris to be with his father, who was thinking of coming back and taking over the studio . . . again.

“You know all these young people,” Darryl told him. “Do you know anybody who could run production? Here’s what I want you to do. At dinner tonight, bring me a list of people who could run the studio.”

That night, Dick handed his father a note. On it was just one word: “Me.” And that was the beginning of Dick’s reign as a studio head.

Dick sold 546 Ocean Front some years before he died in 2012, but I’ll always remember it as the Zanuck house. And Darryl and Dick Zanuck will always be in my heart.

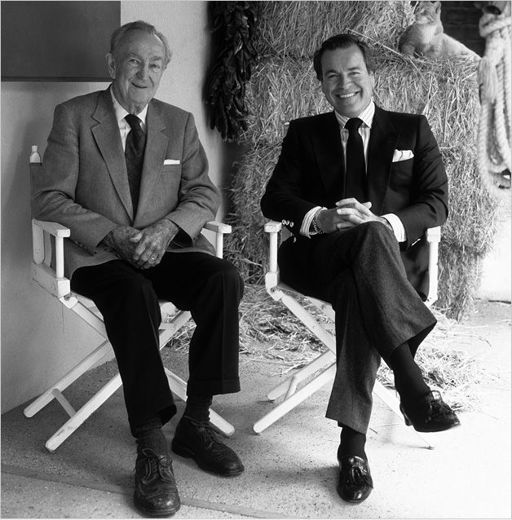

Me with my young friend Richard Zanuck and his first wife, Lili.

Courtesy of the author

As my own career began to flourish and I began circulating among my fellow movie stars in areas full of money, I encountered a number of surprises. For instance, James Cagney’s house on Coldwater Canyon.

The house itself looked like an unpretentious Connecticut farmhouse. It had two stories—the exterior of the first story was finished in fieldstone, the second floor in shingles.

It was not large, with only six or seven markedly small rooms, and a warm, rustic interior. Jim’s study was very masculine, with roughly finished boards, lots of books, a card table, and a piano. The house had been completed just before World War II, and that’s where Jim lived when he was making a movie in town. Otherwise, he was in the east, at either of his farms in Dutchess County or on Martha’s Vineyard.

The Beverly Hills house wasn’t exactly a cottage, but it seemed incomprehensible as a residence for a great star like Cagney. But then Jim wasn’t your typical great star. He always felt that Jack Warner was taking advantage of him, but he was never really successful away from the studio. He broke away a couple of times—once, briefly, in the thirties, and later, during the war and after, when he set up Cagney Productions with his brother Bill.

But the pictures Jim made for himself showcased him not as his fans wanted to see him—snarling, taking on the cops and the world with a gun in his hand—but as he wanted to see himself: in literary material such as

Johnny Come Lately

or

The Time of Your Life

, in which he played a quiet, reflective man in transition. Those pictures would disappoint, and he would troop back to Warner, grumbling the entire time.

There were very few personal touches in Jim’s Hollywood house. One of them was a track that he had constructed right on Coldwater Canyon—his property encompassed ten acres—where I would jog his trotters when I was a teenager. I got the job through the Dornan family, who were good friends of his. There weren’t a lot of grooms around Hollywood at that point, so I lucked into the job.

I was just a kid at that point, so he didn’t have to be nice to me, but he always was. That’s the kind of man Jim Cagney was. He liked people, he was very open, and he was very compassionate about animals. If you cared about animals, Jim was your friend. Since I was young and loved horses, I was one of his people. Ten years later, I died in his arms in

What Price Glory

—one of the great thrills of my life.

Inside Jimmy’s house was a dance studio with a wooden floor and a record player where Jimmy would practice, either to make sure he could still do the steps he’d been doing since his days as a chorus boy in New York or to lose weight for a movie. Dance was Jimmy’s main exercise.

There were never any parties at Jimmy’s home; he and his wife kept to themselves, and I don’t remember him socializing much at all, except for the occasional night out with the Irish mafia—Pat O’Brien, Frank McHugh,

etc.

Jim never displayed much affection for the town of Hollywood—he seemed to regard it as a necessary evil, the financial basis for his real identity as a horse breeder and farmer—but he kept that house to the end of his life. Every winter, when the weather back east got nasty, he and his wife would come back to California and get in touch with their small circle of friends. It was something of a pain—Jim wouldn’t fly, so they had to drive across the country—but by that

time the Coldwater Canyon home had become a refuge for an elderly couple.

Men like Jim didn’t usually hop around when it came to real estate. Likewise Fred Astaire—he built his house in 1960, some six years after his beloved wife Phyllis had died, and he lived in it for the rest of his life with his daughter Ava and his mother. When Ava left home to get married and his mother died, he lived there with a housekeeper. And he continued living there after he married Robyn Smith in 1980, until he died seven years later.

Fred’s home was tastefully done, but not what you might expect—classy, but in a slightly bloodless way. It had designer written all over it, which I suspect was a function of Phyllis’s not being around to personalize it. In addition to books, the library had Fred’s Oscar and his Emmys, but it also had a pool table and a backgammon table. Over the fireplace was a portrait of one of Fred’s prize racehorses. (Half the people in my life have loved horses; the other half have loved dogs.) The dining room was done in period English furniture and Georgian silver.

Fred’s artwork was particularly interesting, as most of it had been done by friends or family rather than by professional artists. Over a cabinet in the dining room was a painting by Ava, and Cecil Beaton had contributed a painting of Fred’s beloved sister Adele. I remember a couple of paintings of birds that had been done by Irving Berlin. They were quietly witty and charming, just like their owner.

In thinking about those times, I’ve realized that the watchword for the Hollywood lifestyle then was “diversity.” Whatever one’s taste

in either people or houses, it could be met. My friend Cliff May was one of the men who saw to the latter. Cliff was the primary practitioner of what would come to be known as the California ranch house. Beginning in the early 1930s and continuing until his death in 1989, Cliff designed more than eighteen thousand ranch houses all over America and as far away as Australia.

Cliff looked like a cowboy. He was slender and handsome, with pale grayish eyes, sandy hair, and an ambling walk. And to his dying day he loved the ladies.

He was a sixth-generation San Diegan, born in 1908. When he was a boy, he would summer at his aunt’s Monterey-style adobe in Santa Margarita, but the influence didn’t immediately take. Cliff never studied architecture; rather, he was a musician—a saxophone player. His father thought music was a ridiculous business and nudged him to do something else. That something else turned into various pursuits—piloting, horses, many other things.

In 1931 he left San Diego State without graduating and he needed to make money. As he recounted to me, he started producing Mission-style furniture, and the pieces sold. Then someone offered him a vacant house in which to display his furniture, and the house, which had been on the market for months, quickly sold. He furnished another house that was for sale, which was also snapped up, and then started building his own. Within four or five years, Cliff had built more than thirty houses in and around San Diego. And then he came to Los Angeles.

In Cliff’s early days as an architect, his style looked a lot like nineteenth-century Californian; he called one of his houses a “haciendita,” which gives you some idea of his traditionalist background.

His great motto was “The plan is shaped by the materials.” His

most famous work is probably the Roper house, which he designed on speculation in 1933, a fairly modest place that showcased his basic architectural ideas and a muted color scheme. Cliff had a formula that stayed the same no matter the fundamental style of the house:

- Fit the house to the site; the facade the public sees is often fairly bland.

- Use natural materials (plaster, hand-worked beams, roof tiles, terra-cotta pavers).

- The patio—or courtyard—is key.

The overall effect was gracious and relaxed. Cliff’s houses were built to be enjoyed; with their wide verandas and muted color schemes, they felt comfortable. The breakfast room was always oriented toward the rising sun, the living room for southern exposure.

Cliff designed to the market; it wasn’t unusual for him to simultaneously work on several different houses in completely different styles. In the 1950s he designed several hundred tract houses in Long Beach that, while ranch houses, derived from the International Style and had very little of the historic detail he loved. They were fairly inexpensive, and they relied on open floor plans with a lot of light and private courtyards.

In the second half of his career, Cliff began getting commissions from movie stars and other wealthy clients, and he returned to his love for period details. Cliff could be completely innovative; in 1952 he designed what he called his Experimental Ranch House for his own family. The roof was primarily fabric and was made to roll up; most of the interior walls were on rubber wheels, so the spaces could be reconfigured at will.

Yours truly with my elegant and talented friend Cliff May.