You Must Remember This (11 page)

Read You Must Remember This Online

Authors: Robert J. Wagner

Just as Joe Schenck had cosigned a house loan for Valentino, so Louis B. Mayer gave Joan Crawford an advance so she could buy a house on North Roxbury in Beverly Hills. The moguls thought that such loans were a good investment in rising stars they believed in, and might also provoke a feeling of gratitude that could only work to the studio’s advantage. A few years later, in 1929, Crawford was an even bigger star, so Mayer OK’d a loan of forty thousand dollars so she could buy a ten-room mansion at 426 North Bristol Circle in Brentwood.

Crawford’s favorite room there was the sunroom, which had windows on three sides and shelves filled with dozens of dolls—Crawford had been a deprived child and saw no reason not to pamper herself with the things she hadn’t had when she was a little girl.

I heard Joan talking about how Billy Haines convinced her to get rid of her collection of hundreds of dolls and dozens of black velvet paintings of dancers. There was no way, he told her, that he could do anything to transform her house into a glamorous environment if she was going to cling to such junk. Joan valued class more than she did her collections, so she gave her dolls and paintings away.

All the prevalent architectural styles were replicated in the palatial movie theaters that were going up across the country. Some were designed as Moorish palaces with ceilings full of twinkling stars; others were Chinese, or Egyptian, but they were all wildly ornate, selling a fantasy that was way beyond the financial reach of 99 percent of the audience that flocked to them. Hollywood was embodying an oversize sense of scale that was an echo of the showmanship that was making the movies. The great sets of the silent era—Fairbanks’s castle for

Robin Hood

and his even vaster sets for

his Arabian Nights fantasy

The Thief of Bagdad

—provided a creative impetus for people within the movie industry and fueled the fantasies of their audiences. Why have a house when you could have a castle?

Right about this time Los Angeles also saw a proliferation of buildings whose forms imitated their functions. A ten-foot-tall orange held an orange juice stand; a huge donut housed a donut shop. There was a place called the Tail of the Pup that looked like a hot dog encased in a bun—you can guess what they sold.

The building that always intrigued me was the Utter-McKinley Mortuary on Sunset and Horn. There was a large clock mounted on top of the building, but it had no hands. Beneath it was a sign that read “24-Hour Service.”

I always thought a clock without hands had a certain ominous “ask not for whom the bell tolls, it tolls for thee” significance that went far beyond undertakers, who never got a full night’s sleep.

Entrepreneurs such as Sid Grauman and Max Factor had their buildings designed to resemble movie sets, and as these buildings were displayed in movies and newsreels, their styles influenced other buildings all over the world, both for and against. It’s possible that without the glamorous excesses of buildings exemplified by Grauman’s Chinese Theatre, the subsequent and—to my mind—overly severe architecture of Mies van der Rohe might never have happened. I suspect that Hollywood’s use of dramatic, extreme architecture—and the public acceptance of it—made the world safe for the more daring architecture that later became the norm.

The studios themselves adopted the same veneer of showmanship. Some of them were more or less architecturally undistinguished factories, like Paramount. But the Chaplin studio on La

Brea was built to resemble a string of Tudor cottages, and Thomas Ince’s studio in Culver City—later bought by Cecil B. DeMille and then by David Selznick—was a replica of George Washington’s Mount Vernon.

And let’s not overlook one of the enduring wonders of Los Angeles architecture: the Witch’s House, built to house the productions of silent film director Irvin Willat. Designed by art director Harry Oliver, it was originally in Culver City but was later moved to Beverly Hills, to the corner of Carmelita Avenue and Walden Drive. Even though it’s been a private residence for the last eighty years, it looks exactly like a set for

Hansel and Gretel

.

All of this exuberant eclecticism bothered the intellectuals, who thought it was vulgar. But Hollywood made its living manufacturing dreams. If it had looked like Newport, the dreams wouldn’t have cascaded over the world as successfully as they did.

And one other thing: these buildings were fun to look at. They were architecture as entertainment.

When Ramon Novarro opted for a tidy house designed by Lloyd Wright, the son of Frank Lloyd Wright, he had MGM art director Cedric Gibbons redecorate entirely in black and silver. Novarro fell so in love with the look that he would ask his dinner guests to comply with the prevailing design scheme and wear only black or silver to his parties.

Gibbons was a huge influence both within the industry and without. His designs for the 1928 Joan Crawford movie

Our Dancing Daughters

showcased Art Deco throughout and helped usher out the heavy Spanish décor. Deco became the look of the young moderns—clean lines and chic.

The movie was successful enough to spawn two sequels, the last of which costarred William Haines, who didn’t care for Gibbons’s

aesthetic and stayed away from Deco when he became a fashionable designer. “It looks like someone had a nightmare while designing a church and tried to combine it with a Grauman theater,” he remarked.

In retrospect, there was a playful aspect to a lot of these houses, as if the actors, directors, and producers were extending the fantasies they created on-screen into their private lives. The houses were partly sets, partly playgrounds—literally.

Many people saw the beautiful sets designed by Cedric Gibbons at MGM or Van Nest Polglase at RKO and asked them to design their houses. Ginger Rogers had a house off Coldwater Canyon that was largely the work of Polglase. Gibbons’s own house, which he designed and built for his marriage to Dolores del Río, was a stunning Moderne masterpiece. Likewise, the art director Harold Grieve, who was married to Jetta Goudal, a star for DeMille in the silent days, developed a business in interior decoration that far surpassed his work for the studios.

By 1937, when I arrived, when you got off the Pacific Electric line in Beverly Hills, nobody noticed the unpaved roads above Sunset, or the bean fields in the flats, or the modest shopping district. Everybody was mesmerized by the vastness of the homes.

When the stock market collapsed in 1929 and the Depression ensued, construction in Los Angeles also collapsed. Construction of new houses and apartments fell from 15,234 in 1929 to 6,600 in 1931. Luxury housing went into a decline, but there were plenty of available places, as silent film people who lost their footing in sound pictures had to downsize. Many of the new stars of the sound era

bought secondhand homes instead of building their own, although there were exceptions. William Powell built a house with a complicated series of features that emerged from walls and rose from the floor. A bar turned into a barbecue by pushing a button; other buttons opened and closed doors. But the wiring was badly done, and there was a comic period when Powell would push a button to go into the parlor, but the kitchen door would open. The house had thirty-two rooms, and something unexpected would happen in each of them.

It would have made a great scene in a comedy starring Cary Grant—or Bill Powell—but Bill, understandably enough, didn’t think it was funny.

“Follow the money” is a brief but telling sentence that has been serving reporters well since the invention of movable type. And the way we lived in Hollywood provides yet another instance of following the money.

In 1941, shortly before I started caddying at the Bel Air Country Club, two thirds of all American families earned between one thousand and three thousand dollars a year. A further 27 percent had incomes of between five hundred and one thousand dollars.

By contrast, even a middling star could reliably expect to earn as much in a week as those two thirds of American families made in a year. A lot of people on the industry’s high end made many multiples of that.

So the houses, the resorts, the restaurants, the luxurious accoutrements that cluttered our lives were a direct result of the fact that, economically speaking, Hollywood wasn’t like the rest of America. Not even close.

By now many businessmen and dozens of movie stars had begun

moving out of downtown Los Angeles and other old neighborhoods into the exciting nouveau riche air of Beverly Hills. Hollywood’s population exploded from 36,000 in 1920 to 157,000 in 1930 and would continue to grow, but it was no longer the chic place to live.

There was a slight gap in the styles of the era; there was no smooth transition between the lavish houses of the 1920s and the more streamlined architecture of the 1930s and ’40s, when architectural styles and interior decoration became noticeably less ornate and extravagant than they had been—the pendulum had swung in the opposite direction, as it always does. By the 1930s Spanish and Italian were out; neocolonial or, for particularly stylish people, Moderne, was in. One of the key transitional buildings was Union Station, which was built between 1934 and 1939, and is a beautiful example of both the Moderne and the Spanish styles—the former the new wave, the latter the old.

In this period you had Mediterranean Revival, but there were also opulent Italian Renaissance places such as Harold Lloyd’s Greenacres. And then there were the polyglot palaces. The director Fred Niblo had a Spanish mansion on Angelo Drive, high above Beverly Hills, but he couldn’t resist adding an English drawing room with paneling that was hundreds of years old. Period romance was all.

John Barrymore bought a comparatively modest house on Tower Road from King Vidor for fifty thousand dollars, then spent a million dollars over the next ten years on improvements. He bought an adjacent four acres, expanding the property to seven acres. He built an entirely separate Spanish house up the hill and connected the two houses with a grape arbor.

Being John Barrymore, he also had to indulge his eccentricities. Above his bedroom was a secret room that he could reach by a

trapdoor and a ladder whenever he needed to get away from his family. By the entrance there was a totem pole painted red and yellow with a fern growing out of the top, like an uncombed head of hair.

By the time Barrymore was through with the project—actually, he just ran out of money—he had sixteen buildings and fifty-five rooms, with more buildings under construction. There was a skeet range, a bowling green, an aviary that held three hundred birds. It was like a little village on a mountaintop in Beverly Hills, all with red tile roofs and iron-grilled windows.

Barrymore couldn’t hold on to his money—none of the Barrymores could—and by 1937 he was being pursued by the IRS for back taxes and had to declare bankruptcy. The vast estate was put up for auction, but the place was such an extension of Barrymore’s idiosyncrasies and onetime income stream that no one bought it.

I never met John Barrymore, although I would have loved to have had the opportunity. I did have the good fortune to be friends with Harold Lloyd, whose house was similarly extravagant. Harold was a very special man. Greenacres, his Italian Renaissance mansion on Benedict Canyon Drive, covered twenty-two acres, forty rooms, and thirty-six thousand square feet—not counting the patios or porches.

Harold told me that by the time the house was finished in 1929, just in time for the stock market crash, he had spent two million dollars. The housewarming party began on a Friday and continued until Monday morning, with changes of bands every four hours to keep everybody energized.

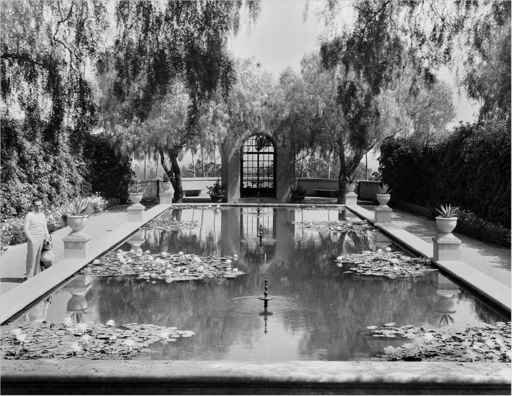

Harold got what he paid for. The house had a seven-car garage and a splendid fountain by the entrance. In fact, it had

twelve

fountains, and you could hear the gurgling of water from practically every place on the property. The entrance hall itself was sixteen feet high, and there was a circular oak staircase attached to the wall without any supports beneath the risers.

Harold was particularly proud of his sunken living room, which had a coffered ceiling with gold leaf on it, elaborate paneling, and a forty-rank pipe organ for concerts or silent film accompaniment. The dining room could sit up to twenty-four guests, and the house carried a staff of thirty-two, sixteen of whom were gardeners. If you didn’t want to take the stairs, an elevator could convey you to the second floor, which held ten bedrooms.

Outside, Harold built a nine-hole golf course and an Olympic-size swimming pool. There were tennis courts and handball courts and even an eight-hundred-foot-long canoe lake adjacent to the golf course. For his three children, he also built a child-size four-room cottage with a thatched roof, complete with electricity, plumbing, and miniature furniture.