You Must Remember This (30 page)

Read You Must Remember This Online

Authors: Robert J. Wagner

It seemed to be a stylish idea at the time.

For the generation just before mine, the Grove was a key site—Mack Sennett discovered Bing Crosby while he was performing there, and Joan Crawford won so many of its dance contests that she became the unofficial Charleston champion of Hollywood.

The chef at the Grove, Henri, was French. He was heavy on local ingredients like avocados, grapefruit, and asparagus, as well as abalone, sand dabs, and little California oysters, which you could order either raw or cooked. The hotel became a familiar setting in the movies; you can glimpse it in the Judy Garland version of

A Star Is Born

, and the Art Deco entrance appears in the Jean Harlow film

Bombshell.

The odd thing is that, for all the fame of the Cocoanut Grove itself, the Ambassador Hotel was never all that financially successful. In the 1950s Paul Williams was hired to do a makeover, and the irony was that Williams, who had designed a lot of fine homes in Beverly Hills and Bel Air—not to mention the Beverly Hills Hotel—would probably not have been able to get a room there because he was African American.

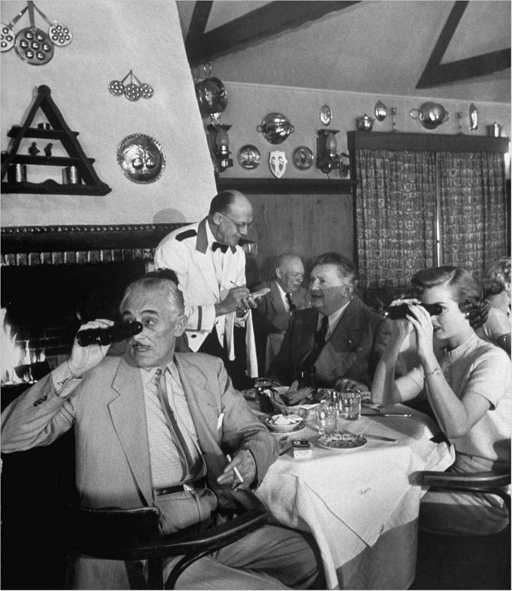

Virginia Bruce, Cliff Edwards, Clarence Brown, Nancy Dover, and their party ring in the new year at the Cocoanut Grove in LA.

Bettmann/CORBIS

The 1964 movie

The Best Man

, with Henry Fonda, has quite a few scenes photographed at the Ambassador, notably the lobby and other public areas. The good times for the hotel permanently ended when Robert Kennedy was assassinated in its kitchen in 1968. The Ambassador, and the Grove, limped on until the hotel finally closed in 1989. It stood derelict for years, the roof of its ballroom sagging under the weight of leaks and its lush gardens becoming wild. Eventually the place was demolished.

A hotel that has had a considerably luckier life is the Chateau

Marmont, off Sunset Boulevard. The Norman-inspired Chateau opened in 1927 at the height of the era of Hollywood excess, and it’s still there, bearing the slightly worn aura of the place where Jean Harlow honeymooned with cameraman Hal Rosson, where the young Howard Hughes entertained his ladies before moving over to the Beverly Hills Hotel.

For Europeans who had come to Hollywood in the wake of war, the culinary scene was grim. When the Viennese Paul Henreid arrived in 1940, he observed that “there was terrible food, with one or two exceptions”—those being Romanoff’s, Perino’s, and Chasen’s. “That was about it. Those were the three places you could go and get a decent meal.”

Perino’s, which opened on Wilshire Boulevard, was spawned by people who had worked at Victor Hugo. It was more than just upscale—it was

swanky

. Alexander Perino was the kind of guy who trained other restaurateurs—he once claimed that eighteen Los Angeles restaurants had been created by his protégés, and it’s certainly possible.

Perino’s didn’t subscribe to any of the gimmicks that some of the other restaurants did. The mood was conservative and the service was excellent—not by the standards of Hollywood, but by the standards of Paris or London. You wore your best to Perino’s—not just clothes, but jewelry as well—because it wasn’t the sort of place where you ordered a hamburger. Alex imported twenty-four-inch-square linen napkins from Ireland, and had a rigid ratio of one waiter for every eight diners to ensure a high level of service.

At Perino’s the bill of fare included dishes like salmon in aspic

and tangerine soufflé. As Paul Henreid observed: “They would have something that was then unheard of, like a crêpe filled with lobster or with crab.” Perino’s served a lot of Italian dishes—some pretty fancy, such as polenta or gnocchi—and lots of fresh fish, especially Dover sole and sand dabs. Alex insisted on homemade brown stock and fresh tomato puree for even a basic Bolognese sauce. Oddly for an Italian gentleman, Alex wouldn’t cook with garlic, which he detested. And he wouldn’t refrigerate his tomatoes, because he believed it destroyed their flavor.

The ultra-upscale Perino’s restaurant.

It was a very chic restaurant, strictly white-glove, and was favored by business types and political movers and shakers—Los Angeles people more than Hollywood people. Frankly, Perino’s was always a bit snobbish for me, but then, it didn’t really cater to the movie crowd the way, for instance, Chasen’s did.

Alex sold the restaurant in 1969, and it kept going for a number of years before closing in the late 1980s, as so many of the once great LA restaurants did. We shot at least one episode of

Hart to Hart

there, and I don’t know if we would have been able to do that while Alex was running the place; while he tolerated movie people,

whom he probably regarded as nouveau riche, he might not have wanted an actual film crew in his restaurant.

I don’t know if the Players would be considered a great restaurant, but it was certainly a great experience. The Players was owned and run by Preston Sturges, the great writer-director of such flamboyant farces as

The Palm Beach Story

and

The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek

. Opened in 1940, it became very popular during the war years. The Players was an old wedding chapel at 8225 Sunset, slightly west of the Chateau Marmont. Sturges converted the chapel at great expense into a three-level entertainment and dining complex. The idea was that you could have a fine meal, then go downstairs and take in a play. When the play ended, Sturges could push a button and the floor leveled out to become a supper club with an orchestra on a revolving stage.

A lot of the actors who starred in Sturges’s movies went there, as well as Humphrey Bogart, Charlie Chaplin, Orson Welles, Willy and Talli Wyler, and—when he was in Hollywood working on a script for Howard Hawks—William Faulkner. Sturges was there

most nights holding court, and sometimes Howard Hughes would join him.

The exterior facade of The Players restaurant. To the right is the Chateau Marmont.

Sturges ran the place like an indulgent uncle. There was a barber shop on the mezzanine level, and if he felt like entertaining some of his close friends, he would close the place for a private party without warning.

The food was excellent. The menu included some French dishes, turkey croquettes, and canapés, and a lot of drinks that Sturges named himself, although he reputedly drank only old-fashioneds.

Sturges comped his friends, and was always coming up with inventions that were expensive and of dubious worth—like tables that swiveled out to provide easy access. He once made plans to build a helicopter pad in the parking lot so that he could take delivery of fish that were still flopping, but the neighbors protested, and it never happened.

In his quiet moments Sturges may have silently counted out how much it was costing him every week to run the place, but since he was Preston Sturges—a profligate personality if ever there was one—I doubt it. However brilliant, he was erratic and a terrible businessman. He poured hundreds of thousands of dollars into the Players until the IRS took it over in 1953.

As the 1940s turned into the 1950s, the Hollywood dining experience on the whole became far more sophisticated. And after the war, as stars began venturing out from Hollywood toward independent production, Europe was no longer just a place for vacations. It followed that Hollywood restaurants began to adopt what their patrons found palatable in countries overseas.

I remember Scandia with particular affection, because the food was so tasty. Scandia was on Sunset Boulevard from the time it opened in 1946, and it kept going until 1989. Early on Scandia cooked primarily brasserie food, more than slightly Germanic—pot roast, brisket, stuffed cabbage, boiled beef with horseradish sauce. Peter Lorre was there every Saturday, and other regulars included Gary Cooper, Ingrid Bergman, Rita Hayworth, and Marilyn Monroe.

Over the years the menu evolved and began featuring more sophisticated dishes, including a gravlax appetizer that had a spectacular mustard dill sauce. Kenneth Hansen, who was the chef and ran the place, would make occasional trips to Scandinavia and bring back new recipes. He also arranged for seafood from the North Atlantic to be flown in year-round.