1812: The Navy's War (45 page)

The first two months of Rodgers’s cruise were frustrating. He missed the Jamaica convoy, and thick fog hindered him as he hunted along the eastern edge of the Grand Banks, looking for vessels bound for Canada. At the end of May he took up a position west of the Azores, but again with no results until the second week of June, when he captured two small merchantmen, a letter of marque, and a packet. He sent the merchantmen to France as prizes and the packet as a cartel ship to England with seventy-eight prisoners, hoping to annoy the Admiralty.

Rodgers then set sail for the northern area of the British Isles, something he had wanted to do since the war began. But as luck would have it, he did not see another ship until he was near the Shetland Islands off the northeast coast of Scotland. By then his provisions and water were running low, and he steered northeast for Bergen, Norway, to resupply.

Norway was part of Denmark—a bitter enemy of Britain. An American warship had never visited Bergen before, so when people found out who Rodgers was, they extended their warmest hospitality. Unfortunately it did not include the food he needed. Bread and other provisions were simply not available. All the Norwegians could give him were water and a tiny amount of cheese and rye meal.

When the Admiralty discovered the

President

had put into Bergen, it tried hard to catch her. On July 13 the

Times

reported that Rodgers was refitting and watering there, but by then he had already left. He stood out from Bergen on July 2 in search of a British convoy from the Russian port of Archangel. In the next two weeks he captured two small merchantmen, and on the eighteenth he met and joined forces with the American privateer

Scourge

, under Captain Samuel Nicoll, out of New York. Nicoll had been at work since June, along with another famous privateer, the

Rattlesnake

out of Philadelphia. During a busy month, the two raiders had captured twenty-two prizes. They did so well that the Admiralty thought they were part of an American squadron led by Rodgers. In fact, they were but a small part of an armada of American privateers swarming around the British Isles. The embarrassed Admiralty tried to get rid of them but never succeeded. The Royal Navy’s hunters were too few and the American marauders too many.

President

had put into Bergen, it tried hard to catch her. On July 13 the

Times

reported that Rodgers was refitting and watering there, but by then he had already left. He stood out from Bergen on July 2 in search of a British convoy from the Russian port of Archangel. In the next two weeks he captured two small merchantmen, and on the eighteenth he met and joined forces with the American privateer

Scourge

, under Captain Samuel Nicoll, out of New York. Nicoll had been at work since June, along with another famous privateer, the

Rattlesnake

out of Philadelphia. During a busy month, the two raiders had captured twenty-two prizes. They did so well that the Admiralty thought they were part of an American squadron led by Rodgers. In fact, they were but a small part of an armada of American privateers swarming around the British Isles. The embarrassed Admiralty tried to get rid of them but never succeeded. The Royal Navy’s hunters were too few and the American marauders too many.

Rodgers shaped a course for the North Cape off Norway’s island of Mageroya. On the way he captured two more prizes, both brigs in ballast, which he burned after removing their crews and stores. He reported that “sun in that latitude, at that season, appeared at midnight several degrees above the horizon.” On the nineteenth of July, with the

Scourge

in company, lookouts on the

President

spied two large British ships in the distance, and judging them to be a line-of-battle ship and a frigate, Rodgers put on all sail to avoid them. The

Scourge

did the same

,

parting company with the

President

. The British men-of-war ignored the smaller ship and concentrated on the

President

, a prize that, if caught, would have made their captains heroes in Britain. Capturing Rodgers was a high priority for the Admiralty.

Scourge

in company, lookouts on the

President

spied two large British ships in the distance, and judging them to be a line-of-battle ship and a frigate, Rodgers put on all sail to avoid them. The

Scourge

did the same

,

parting company with the

President

. The British men-of-war ignored the smaller ship and concentrated on the

President

, a prize that, if caught, would have made their captains heroes in Britain. Capturing Rodgers was a high priority for the Admiralty.

Ironically, Rodgers was running from the very ships he had hoped to find. The men-of-war chasing him were the 38-gun frigate

Alexandria

and the 16-gun sloop of war

Spitfire

. Unfortunately, fog obscured his view, and he could not identify them. The

President

and the

Scourge

together could have easily beaten them; even the

President

alone could have.

Alexandria

and the 16-gun sloop of war

Spitfire

. Unfortunately, fog obscured his view, and he could not identify them. The

President

and the

Scourge

together could have easily beaten them; even the

President

alone could have.

After eluding his pursuers, Rodgers stood south, shaping a course to take him back to Scotland’s northwestern coast, where he could watch for vessels at the northern end of the Irish Channel. He was there at the same time that Henry Allen and the

Argus

were patrolling at the southern end of the Channel. The tiny American navy, which was supposed to be blockaded in its home ports, was instead operating at both ends of a major British waterway. During the succeeding days, Rodgers captured three ships and sent them to England as cartels—more salt in the wound for the Admiralty.

Argus

were patrolling at the southern end of the Channel. The tiny American navy, which was supposed to be blockaded in its home ports, was instead operating at both ends of a major British waterway. During the succeeding days, Rodgers captured three ships and sent them to England as cartels—more salt in the wound for the Admiralty.

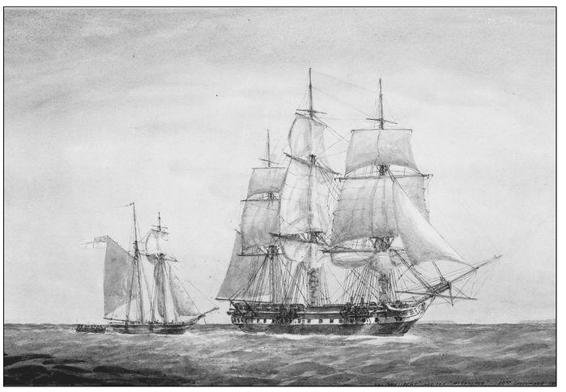

Figure 19.1: Irwin Bevan, President

and

High Flyer

, 23 September 1813

(courtesy of Mariner’s Museum, Newport News, Virginia).

and

High Flyer

, 23 September 1813

(courtesy of Mariner’s Museum, Newport News, Virginia).

He knew their lordships would be outraged and would intensify their hunt for him, which was gratifying, but at the same time he did not want to tempt fate any further. With provisions running low, he headed home, setting a course for the Grand Banks off Newfoundland, where he made two more captures and sent them as prizes to the United States.

He continued southwest, and near the southern shoal of Nantucket he spotted an armed schooner that looked interesting. When he saw her signaling, he looked at the Royal Navy’s private signals he had acquired and answered appropriately. Whereupon, His Majesty’s 5-gun schooner

High Flyer

, Admiral Warren’s tender, sped toward the

President

with the British ensign flying and hove to under her stern. Lieutenant George Hutchinson, the schooner’s dimwitted skipper, believed the

President

was His Majesty’s frigate

Seahorse

. One of Rodgers’s lieutenants, outfitted in a British uniform, went aboard the

High Flyer

and brought Hutchinson back to the

President

to meet Rodgers. Still believing he was on the

Seahorse

and that Rodgers was her captain, Hutchinson handed over Admiral Warren’s instructions detailing the number of British squadrons along the American coast, their force, and their relative positions, along with pointed orders to capture the

President

. Hutchinson was unaware that he was talking to Rodgers until the commodore introduced himself.

High Flyer

, Admiral Warren’s tender, sped toward the

President

with the British ensign flying and hove to under her stern. Lieutenant George Hutchinson, the schooner’s dimwitted skipper, believed the

President

was His Majesty’s frigate

Seahorse

. One of Rodgers’s lieutenants, outfitted in a British uniform, went aboard the

High Flyer

and brought Hutchinson back to the

President

to meet Rodgers. Still believing he was on the

Seahorse

and that Rodgers was her captain, Hutchinson handed over Admiral Warren’s instructions detailing the number of British squadrons along the American coast, their force, and their relative positions, along with pointed orders to capture the

President

. Hutchinson was unaware that he was talking to Rodgers until the commodore introduced himself.

Before the

High Flyer

became the Admiral’s tender, she had been an American privateer out of Baltimore—and a famous one. British Captain John P. Beresford captured her in heavy seas on January 9, 1813, in the 74-gun

Poictiers

; he was very proud of his success and couldn’t wait to tell Warren. Beresford reported that the schooner was “a particularly fine vessel, coppered and copper fastened, and sails remarkably fast.” She was typical of the Baltimore schooners that were giving the Admiral so much trouble. Admiral Warren was delighted to have the

High Flyer

for a trophy. One can only imagine his reaction when she was so easily recaptured, and by his nemesis Rodgers.

High Flyer

became the Admiral’s tender, she had been an American privateer out of Baltimore—and a famous one. British Captain John P. Beresford captured her in heavy seas on January 9, 1813, in the 74-gun

Poictiers

; he was very proud of his success and couldn’t wait to tell Warren. Beresford reported that the schooner was “a particularly fine vessel, coppered and copper fastened, and sails remarkably fast.” She was typical of the Baltimore schooners that were giving the Admiral so much trouble. Admiral Warren was delighted to have the

High Flyer

for a trophy. One can only imagine his reaction when she was so easily recaptured, and by his nemesis Rodgers.

After his conversation with the hapless Hutchinson, Rodgers sailed for Newport and slipped into port with his prize, dropping anchor on September 26, thwarting Britain’s mighty effort to catch him. Warren wrote to the Admiralty, “I made the best disposition in my power to intercept his return to port,” but that had not been enough. Warren had committed an unprecedented twenty-five warships to the effort. The frigates

Junon

and

Orpheus

and the sloop of war

Loup-Cervier

(the former American ship

Wasp

) were patrolling off Newport, but they never saw the

President

or the

High Flyer

.

Junon

and

Orpheus

and the sloop of war

Loup-Cervier

(the former American ship

Wasp

) were patrolling off Newport, but they never saw the

President

or the

High Flyer

.

In the end, Rodgers’s cruise had not been spectacular, but he did capture twelve vessels and diverted a substantial number of enemy warships from other duties to hunt for him. Secretary Jones considered that worthwhile. Rodgers was not resting on his laurels, however. He moved the

President

to Providence for better protection and set to work getting her repaired and provisioned for another cruise. By the middle of November she was ready, but Rodgers did not attempt to sortie until the first week of December. Adverse weather and the British warships off Block Island kept him in port until December 4, when he sailed out, eluding the battleship

Ramillies

and the frigates

Loire

and

Orpheus

, as well as the smaller vessels cruising in shore.

President

to Providence for better protection and set to work getting her repaired and provisioned for another cruise. By the middle of November she was ready, but Rodgers did not attempt to sortie until the first week of December. Adverse weather and the British warships off Block Island kept him in port until December 4, when he sailed out, eluding the battleship

Ramillies

and the frigates

Loire

and

Orpheus

, as well as the smaller vessels cruising in shore.

Rodgers’s departure was another blow to Warren. It reinforced the Admiralty’s judgment that he was not up to the job and had to be replaced.

The British were interested as much in the

Constitution

as they were the

President

. After her return to Boston early in 1813, they kept a close eye on the harbor. Charles Stewart had the big frigate ready for sea by the end of September, but adverse winds and the blockade kept him in port until the last day of the year, when he slipped out to sea. A determined skipper with a good ship could always break free in bad weather. No blockade could have stopped Stewart. Nonetheless, the Admiralty blamed Warren.

Constitution

as they were the

President

. After her return to Boston early in 1813, they kept a close eye on the harbor. Charles Stewart had the big frigate ready for sea by the end of September, but adverse winds and the blockade kept him in port until the last day of the year, when he slipped out to sea. A determined skipper with a good ship could always break free in bad weather. No blockade could have stopped Stewart. Nonetheless, the Admiralty blamed Warren.

WHILE RODGERS AND Stewart were able to get to sea, Decatur remained trapped in the Thames River with the

United States

,

Macedonian

, and

Hornet

. When he fled there in June, he concentrated on escaping, looking for “the first good wind and a dark night” to break out and return to New York via Long Island Sound. But if that were impossible, he wrote Secretary Jones, he would take his ships six miles upriver, where “the channel is very narrow and intricate and not a sufficient depth of water to enable large ships to follow.” The place he had in mind was Gales Ferry, six miles above New London. Decatur thought he’d be safe there if he had more twenty-four-pounders and some gunboats from the New York flotilla.

United States

,

Macedonian

, and

Hornet

. When he fled there in June, he concentrated on escaping, looking for “the first good wind and a dark night” to break out and return to New York via Long Island Sound. But if that were impossible, he wrote Secretary Jones, he would take his ships six miles upriver, where “the channel is very narrow and intricate and not a sufficient depth of water to enable large ships to follow.” The place he had in mind was Gales Ferry, six miles above New London. Decatur thought he’d be safe there if he had more twenty-four-pounders and some gunboats from the New York flotilla.

British Commodore Robert Oliver intended to keep Decatur bottled up. He ordered Captain Hardy in the 74-gun

Ramillies

and Captain Hugh Pigot in the 36-gun

Orpheus

to return to their station off the Thames, while he went back to patrolling off Sandy Hook in the 74-gun

Valiant

, accompanied by the 44-gun

Acasta

. Decatur was immediately aware of the switch. He was also painfully aware of the scandalous traffic in goods and intelligence between the British ships and traitors onshore. He was determined to interrupt that traffic and to harass, and even sink, the

Ramillies

and the

Orpheus

.

Ramillies

and Captain Hugh Pigot in the 36-gun

Orpheus

to return to their station off the Thames, while he went back to patrolling off Sandy Hook in the 74-gun

Valiant

, accompanied by the 44-gun

Acasta

. Decatur was immediately aware of the switch. He was also painfully aware of the scandalous traffic in goods and intelligence between the British ships and traitors onshore. He was determined to interrupt that traffic and to harass, and even sink, the

Ramillies

and the

Orpheus

.

When Congress passed the so-called “Torpedo Act” in March 1813, all sorts of inventions appeared. On June 25 John Scutter Jr., using one of the more promising devices, made an attempt on the

Ramillies

. Scutter outfitted the schooner

Eagle

with food and a huge bomb that exploded when sufficient food was removed. He explained that the device contained “a quantity of powder with a great quantity of combustables . . . placed beneath the articles the enemy were to hoist out. The act of displacing these articles was to cause an explosion, by a cord fasten’d to the striker of a common gun lock, which ignited with a train of powder—the first or second hogshead moved the cord.”

Ramillies

. Scutter outfitted the schooner

Eagle

with food and a huge bomb that exploded when sufficient food was removed. He explained that the device contained “a quantity of powder with a great quantity of combustables . . . placed beneath the articles the enemy were to hoist out. The act of displacing these articles was to cause an explosion, by a cord fasten’d to the striker of a common gun lock, which ignited with a train of powder—the first or second hogshead moved the cord.”

Scutter hoped the

Ramillies

would bring the

Eagle

alongside, and when she attempted to haul the food out, the explosion would blow a huge hole in her and sink her. Completely taken in by Scutter, Hardy sent barges to capture the

Eagle

and bring her to his battleship. Bad weather forced the barges to anchor the

Eagle

, however, and move the food themselves, causing a huge explosion that killed all aboard the boats but did not touch the

Ramillies

.

Ramillies

would bring the

Eagle

alongside, and when she attempted to haul the food out, the explosion would blow a huge hole in her and sink her. Completely taken in by Scutter, Hardy sent barges to capture the

Eagle

and bring her to his battleship. Bad weather forced the barges to anchor the

Eagle

, however, and move the food themselves, causing a huge explosion that killed all aboard the boats but did not touch the

Ramillies

.

Another attempt was made using a submarine similar to David Bushnell’s famous

Turtle

, which was deployed during the War of Independence and came very close to sinking Admiral Howe’s flagship

Eagle

in New York Harbor in 1776. Unfortunately, the bomb the new submarine carried could not be fastened to the

Ramillies

’s hull, and the attempt failed, but it came close enough that afterward Hardy swept his hull every two hours.

Turtle

, which was deployed during the War of Independence and came very close to sinking Admiral Howe’s flagship

Eagle

in New York Harbor in 1776. Unfortunately, the bomb the new submarine carried could not be fastened to the

Ramillies

’s hull, and the attempt failed, but it came close enough that afterward Hardy swept his hull every two hours.

Although these two attempts failed, Decatur was determined to try again, using one of Robert Fulton’s inventions. When Decatur was in New York, he had been captivated by Fulton’s active imagination, particularly his thoughts on torpedoes and submarines. Fulton visited New London and wanted to try out a new invention he called an underwater cannon. His torpedoes and mines had never proven practical. He thought he would overcome his difficulties with a cannon that could shoot underwater. Decatur was anxious for him to try, but the experiment never came off.

Captain Hardy and Admiral Warren were offended by Decatur’s use of these “infernal machines,” and Hardy threatened countermeasures. He announced that if any more attempts were made, he would retaliate against the coast, bombarding every place in range.

While Decatur was on the attack with unconventional means, he was also strengthening the defenses at Gales Ferry, where he had moved his three ships. Worried that Hardy would make a determined effort to recover the

Macedonian

, he built a fortification known as Fort Decatur, which protected approaches to Gales Ferry from the water. Decatur also received two companies of regulars to defend the fort from a land attack. He fashioned a huge chain that prevented warships from rushing up the Thames River. His defenses were solid—in fact, too solid for James Biddle, captain of the

Hornet

, who had his mind fixed on escaping. He thought Decatur should devote his energies to busting out rather than defending against an attack. “Decatur has lost very much of his reputation by his continuance in port,” Biddle wrote to his brother. “Indeed he has certainly lost all his energy and enterprise.”

Macedonian

, he built a fortification known as Fort Decatur, which protected approaches to Gales Ferry from the water. Decatur also received two companies of regulars to defend the fort from a land attack. He fashioned a huge chain that prevented warships from rushing up the Thames River. His defenses were solid—in fact, too solid for James Biddle, captain of the

Hornet

, who had his mind fixed on escaping. He thought Decatur should devote his energies to busting out rather than defending against an attack. “Decatur has lost very much of his reputation by his continuance in port,” Biddle wrote to his brother. “Indeed he has certainly lost all his energy and enterprise.”

Other books

Born to Be Wylde by Jan Irving

Racked (A Lt. Jack Daniels / Nicholas Colt mystery) by Hardin, Jude, Konrath, J.A.

The Watercolourist by Beatrice Masini

The Natural Superiority of Women by Ashley Montagu

Valentine Joe by Rebecca Stevens

Breaking Braydon by MK Harkins

One Way or Another: A Novel by Elizabeth Adler

Rebound by Michael Cain

My Heart Laid Bare by Joyce Carol Oates