1812: The Navy's War (72 page)

Lambert sent Dickson across the river to see what Thornton’s situation was, and he held a council of war with those officers who were still alive. By then, American fire had ceased. Jackson’s artillery stopped around two o’clock, but his infantry had stopped five hours earlier for lack of targets. Lambert’s situation was desperate. If he renewed the attack and it failed, which it almost surely would, he would have to surrender. He had no alternative but to retreat.

On the other side of the river, Dickson discovered that, although Thornton was severely wounded and reinforcements were needed, he had dispatched Morgan’s militiamen easily and captured Patterson’s battery. The commodore had fired at the British across the river with good effect and had turned a gun on Thornton as well, but as the British regulars closed in, Patterson spiked his guns in great haste and withdrew. Thornton easily cleaned them and carried them to a point where he could enfilade Jackson’s line, which could have destroyed him. Before Thornton could execute, however, Lambert ordered him back. Jackson was very lucky, and he knew it. When Thornton withdrew, Patterson returned, fixed the guns, and used them again against Lambert, cannonading sporadically day and night. Jackson never considered going on the offensive for the same reasons he did not do so after the previous engagements. He feared the British regulars, even in their weakened condition, would destroy his militiamen.

The butcher’s bill on the British side was horrendous—291 killed and 1,262 wounded on January 8. An additional 484 were listed as missing, but they were surely either prisoners or deserters. Jackson had 13 killed, 39 wounded, and 19 missing, probably Morgan’s men. The numbers were so astounding that Jackson told Monroe they “may not everywhere be fully credited.”

THE NEXT DAY, Cochrane attacked Fort St. Philip, which Jackson had strengthened long ago when he first came to New Orleans. The fort had a solid battery of twenty-nine twenty-four-pounders, two thirty-two-pounders, heavy mortars, and howitzers. Commodore Patterson’s sole remaining gunboat, under Lieutenant Thomas Cunningham, was in the water outside. Four hundred regulars manned the fort under Major Walter Overton.

Cochrane sent five small ships to test the fort’s defenses. They arrived on January 9 and shelled it from a distance of one mile. That night they tried running past the fort with a fair wind, but they could not make it and returned to their previous position. They resumed the bombardment and kept at it until January 18. During the nine days, a thousand shells fell into the fort but had little effect.

Cochrane’s maneuver was a distraction designed to hold Jackson’s attention while Lambert went about the difficult, time-consuming business of readying his army for a retreat back to their ships off Cat Island. Five hundred British soldiers had surrendered to Jackson, and many others had deserted, but Lambert still had a powerful force. He kept Jackson off balance by pretending he was going to attack again, and Jackson had to take the threat seriously, particularly with Cochrane’s bombardment going on. If Cochrane could get his warships up the Mississippi, he might turn the tables on the Americans.

On January 18 Lambert was ready, and he conducted a masterly, secret retreat, while Jackson waited for another onslaught. The sorely tried British troops made it back to their troop transports off Cat Island and climbed aboard, chilled to the bone. They were hoping to weigh anchor immediately, but bad weather delayed the fleet, and it did not sortie until January 25.

When Lambert was safely away, he decided to have another go at Fort Bowyer, and in this he easily succeeded. Major Lawrence surrendered with four hundred men on February 11. Lambert could now threaten Mobile and then possibly New Orleans itself again. But on February 14 he received word that the war was over, and he could relax. His men enjoyed Dauphin Island, which was something of a paradise.

Lambert still had to negotiate with Jackson about prisoners and former slaves, who left with the British. Jackson wanted all the slaves back, viewing them simply as property. Lambert considered them human beings, and he refused to return anyone who did not want to go, even though they were more mouths to feed and a burden on his resources. He stuck to his guns; he would not return anyone to slavery. The ex-slaves who wanted their freedom sailed away with him.

THE SUCCESSFUL DEFENSE of New Orleans had a decided impact on the attitude of Liverpool, Castlereagh, and their colleagues toward the United States. The military prowess of America now appeared far more substantial, and this new assessment would help alter relations between the two countries from then on. Britain and America, through two centuries, never fought each other again. The battle at New Orleans contributed to bringing about a remarkable new relationship. Thus, even though the battle occurred after the peace treaty was signed, it played a major role in winning the peace that followed.

CHAPTER THIRTY-TWO

An Amazing Change

W

HEN THE NEW year of 1815 began, a pervasive gloom hung over Washington while the city waited anxiously for reports from New Orleans and Ghent. Prospects for an acceptable peace appeared remote, and the British invasion of New Orleans seemed certain to succeed. Madison thought it was a good possibility that Spain would secretly turn Florida over to Britain. If Cochrane then captured New Orleans, the British would control the southern extremity of the United States and threaten all of Louisiana. They would also have northern Maine. The outcome of the meeting of disgruntled Federalists at Hartford was unknown but troubling. The country appeared to be coming apart.

HEN THE NEW year of 1815 began, a pervasive gloom hung over Washington while the city waited anxiously for reports from New Orleans and Ghent. Prospects for an acceptable peace appeared remote, and the British invasion of New Orleans seemed certain to succeed. Madison thought it was a good possibility that Spain would secretly turn Florida over to Britain. If Cochrane then captured New Orleans, the British would control the southern extremity of the United States and threaten all of Louisiana. They would also have northern Maine. The outcome of the meeting of disgruntled Federalists at Hartford was unknown but troubling. The country appeared to be coming apart.

Even though the belief that the war would continue was widespread, the president could not get Congress to enact a system of taxation or a national bank to properly finance it. Nor would Congress approve the army Madison wanted. The United States seemed to be growing weaker, while Britain appeared stronger than ever. Thousands of veteran British troops and some of Wellington’s best generals were in Canada. And Admiral Yeo was again dominant on Lake Ontario. How long would it be before he regained control of lakes Erie and Champlain? All of these problems would disappear if the war ended, but the president saw little chance of that. What seemed more likely was a continuation of the fighting with an inadequate army and navy, and a divided country whose government was essentially bankrupt.

The gloom in Washington was relieved somewhat by news the second week of January that the ultrasecret Hartford Convention had issued a moderate report that reflected the views of most Federalists, who, although unhappy with Madison, did not want to secede and ignite a civil war. “The proceedings are tempered with more moderation than was to have been expected,” the

National Intelligencer

wrote. “A separation from the Union, so far from being openly recommended, is the subject only of remote illusion.”

National Intelligencer

wrote. “A separation from the Union, so far from being openly recommended, is the subject only of remote illusion.”

This relatively good news was more than offset by word that on January 15 a British squadron forced Stephen Decatur to surrender the 44-gun

President

off New York after a bloody fight in which Decatur lost one-fifth of his crew, including Lieutenant Paul Hamilton, the son of the former secretary of the navy, who was cut in half by a cannonball.

President

off New York after a bloody fight in which Decatur lost one-fifth of his crew, including Lieutenant Paul Hamilton, the son of the former secretary of the navy, who was cut in half by a cannonball.

Decatur’s depressing story began during the evening of January 14, when he saw an opening and stood out from New York. A snowstorm had blown the British blockaders out to sea. Decatur had pilots at the bar off Sandy Hook positioning boats with blazing lights to mark a safe passage. But “owing to some mistake of the pilots” (or treachery) the

President

ran aground, where she struck heavily for an hour and a half, breaking rudder braces, cracking masts, and making her hogged. The tide rose, and it was necessary to force her over the bar lest she get stuck again. By ten o’clock Decatur was finally off the treacherous sand. He needed to return to port for repairs, but a strong westerly forced him out to sea. He sailed along the shore of Long Island for fifty miles and then steered southeast by east, hoping to break free.

President

ran aground, where she struck heavily for an hour and a half, breaking rudder braces, cracking masts, and making her hogged. The tide rose, and it was necessary to force her over the bar lest she get stuck again. By ten o’clock Decatur was finally off the treacherous sand. He needed to return to port for repairs, but a strong westerly forced him out to sea. He sailed along the shore of Long Island for fifty miles and then steered southeast by east, hoping to break free.

Decatur’s hopes were dashed, however, when at five o’clock in the morning lookouts spied three ships ahead. He had run into the British squadron. He immediately hauled up and tried passing to the northward of them, but he soon discovered that four ships were chasing him. The lead one was a razee (the 56-gun

Majestic

), and she commenced firing, but with no effect. At noon the

President

was outdistancing the razee, but another large ship (the 50-gun

Endymion

) was gaining because of the injuries the

President

had sustained and the amount of water she was taking in. Decatur immediately started lightening the ship by starting the water, cutting the anchors, and throwing overboard provisions, cables, spare spars, boats, “and every article that could be got at,” while keeping the sails wet from the royals down to coax every bit of speed out of her.

Majestic

), and she commenced firing, but with no effect. At noon the

President

was outdistancing the razee, but another large ship (the 50-gun

Endymion

) was gaining because of the injuries the

President

had sustained and the amount of water she was taking in. Decatur immediately started lightening the ship by starting the water, cutting the anchors, and throwing overboard provisions, cables, spare spars, boats, “and every article that could be got at,” while keeping the sails wet from the royals down to coax every bit of speed out of her.

At three o’clock Decatur had a light wind, but the ship in chase had a strong breeze, and she was coming up fast. The

Endymion

began firing her bow chasers, and Decatur responded with stern guns. By five o’clock the

Endymion

was close on the

President

’s starboard quarter, where neither Decatur’s stern guns nor his quarter guns would bear. He was steering east by north; the wind was from the northwest. Dusk was approaching, and the

President

was being cut up without being able to fight back. Decatur tried to close and board, but the

Endymion

was yawing from time to time to keep her distance and fire with impunity.

Endymion

began firing her bow chasers, and Decatur responded with stern guns. By five o’clock the

Endymion

was close on the

President

’s starboard quarter, where neither Decatur’s stern guns nor his quarter guns would bear. He was steering east by north; the wind was from the northwest. Dusk was approaching, and the

President

was being cut up without being able to fight back. Decatur tried to close and board, but the

Endymion

was yawing from time to time to keep her distance and fire with impunity.

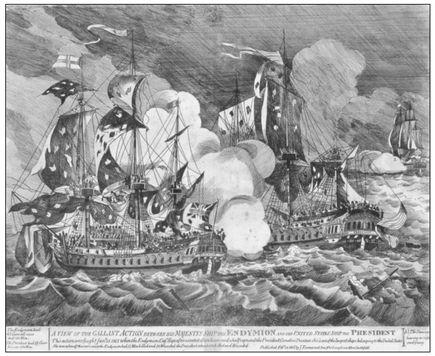

Figure 32.1:

President

versus

Endymion

(courtesy of Naval Historical Center).

President

versus

Endymion

(courtesy of Naval Historical Center).

Desperate to get out of this deadly trap, Decatur abruptly turned south and brought the enemy abeam. A savage battle ensued broadside to broadside for the next two and a half hours, during which Decatur’s superb gunnery dismantled the

Endymion

. For several minutes, the British ship was such a wreck she could not fire a gun.

Endymion

. For several minutes, the British ship was such a wreck she could not fire a gun.

By now, it was 8:30, and two more enemy ships were coming up, the 38-gun frigates

Pomone

and

Tenedos

. Decatur threw on every sail he could and tried to outrun them, but by eleven o’clock the

Pomone

had caught up with him. Visibility was poor enough that Decatur thought the

Tenedos

was close as well, but she was much farther back, perhaps two or three miles.

Pomone

and

Tenedos

. Decatur threw on every sail he could and tried to outrun them, but by eleven o’clock the

Pomone

had caught up with him. Visibility was poor enough that Decatur thought the

Tenedos

was close as well, but she was much farther back, perhaps two or three miles.

The

Pomone

fired two devastating broadsides into the struggling

President

, causing Decatur to examine his alternatives. With one-fifth of the crew killed or wounded, his ship badly damaged, and so many enemy ships opposed to him, with no chance of escaping, he decided to strike his colors. Twenty-five of his veteran crew were dead and sixty wounded. Many of the men had been with Decatur when he fought the

Macedonian

. The British took the

President

and prisoners to Bermuda, where the big frigate, so long sought by the Admiralty, was repaired and taken to England.

Pomone

fired two devastating broadsides into the struggling

President

, causing Decatur to examine his alternatives. With one-fifth of the crew killed or wounded, his ship badly damaged, and so many enemy ships opposed to him, with no chance of escaping, he decided to strike his colors. Twenty-five of his veteran crew were dead and sixty wounded. Many of the men had been with Decatur when he fought the

Macedonian

. The British took the

President

and prisoners to Bermuda, where the big frigate, so long sought by the Admiralty, was repaired and taken to England.

The loss of the

President

dramatically increased the sense of doom in Washington—but that pervasive pessimism disappeared practically overnight as wonderful news began flooding into the capital. On February 4, incredible, scarcely believable reports arrived of victory at New Orleans. Everyone breathed a giant sigh of relief. Only seven days later, on February 11, the British sloop of war

Favorite

, after a tempestuous passage, sailed into New York with the peace treaty.

President

dramatically increased the sense of doom in Washington—but that pervasive pessimism disappeared practically overnight as wonderful news began flooding into the capital. On February 4, incredible, scarcely believable reports arrived of victory at New Orleans. Everyone breathed a giant sigh of relief. Only seven days later, on February 11, the British sloop of war

Favorite

, after a tempestuous passage, sailed into New York with the peace treaty.

On the evening of February 13, the treaty was delivered to the secretary of state in Washington, and the following day the city erupted in a giant celebration. Torches and candles were everywhere. The charred reminders of the fires of August could not dampen the bliss. Overnight, the entire complexion of American politics changed, and everywhere a rebirth of national confidence was evident. Boston and all of New England were deliriously happy. The Senate ratified the treaty unanimously, and on February 17 an enormously relieved president declared the war was over.

The actual terms of the peace treaty seemed unimportant; the country had been saved from the abyss, and that was enough. People would have willingly paid a much higher price for peace. The terms turned out to be relatively benign. In fact, they were much better than expected. The commissioners’ fear that the country would be unhappy with their compromises turned out to be unfounded.

In the midst of these momentous events, three delegates, Harrison Gray Otis, William Sullivan, and Thomas Perkins, arrived in Washington from Boston to press the Hartford Convention’s demand that the states be allowed to use federal tax money to pay for their defense. Governor Strong had appointed them. They arrived on February 13, the day before news of peace became public. The delegates already knew about New Orleans and were anticipating a frosty reception, but the unexpected peace turned their mission into a pathetic joke. They called upon the secretaries of War and the Treasury and were introduced to the president, but Madison treated them coldly. Otis was greatly annoyed. He wrote to his wife, calling the president “a mean and contemptible little blackguard.” After the way Massachusetts Federalists had treated Madison, it is hard to understand why Otis expected any other kind of reception.

Other books

Force Me - Asking For It by Karland, Marteeka, Azod, Shara

Marcia Schuyler by Grace Livingston Hill

Dolls Behaving Badly by Cinthia Ritchie

Murder! Too Close To Home by J. T. Lewis

How to Woo a Reluctant Lady by Sabrina Jeffries

Dreamseeker by C.S. Friedman

Nocturne by Helen Humphreys

Serenading Stanley by John Inman

El rapto de la Bella Durmiente by Anne Rice

The Scorpion's Gate by Richard A. Clarke