1812: The Navy's War (75 page)

Wasting no time, Decatur prepared the treaty and dispatches and sent them to Washington in the

Epervier

, along with the ten freed prisoners. Before she left, he changed her officers, putting Lieutenant John Shubrick, first of the

Guerriere

, in command and transferring Lieutenant Downes to the

Guerriere

, making him the new flag captain. Downes was replacing William Lewis, who was returning to the United States. Decatur made these odd changes as a favor to Lewis, so that he could go home and be with his new wife. Lieutenant Neale was also permitted the same indulgence; he had married the sister of Lewis’s wife. Sadly, the

Epervier

never made it back. She went down with all hands in a hurricane.

Epervier

, along with the ten freed prisoners. Before she left, he changed her officers, putting Lieutenant John Shubrick, first of the

Guerriere

, in command and transferring Lieutenant Downes to the

Guerriere

, making him the new flag captain. Downes was replacing William Lewis, who was returning to the United States. Decatur made these odd changes as a favor to Lewis, so that he could go home and be with his new wife. Lieutenant Neale was also permitted the same indulgence; he had married the sister of Lewis’s wife. Sadly, the

Epervier

never made it back. She went down with all hands in a hurricane.

Scurvy had now begun to appear in the squadron, and Decatur stopped it by sailing to Cagliari on the southern coast of Sardinia for ten days of rest and recuperation. Afterward, he traveled to Tunis to settle matters with the bey, arriving in Tunis Bay on July 25, with a six-ship squadron—the

Guerriere

,

Macedonian

,

Constellation

,

Ontario

,

Flambeau

, and

Spitfire

. The bey had violated Tunis’s treaty with the United States by allowing the British brig

Lyra

during the recent war to take two prizes belonging to the American privateer

Abellino

out of the Bay of Tunis to Malta and for allowing local merchants to obtain the contents of those ships much below their real value. Decatur demanded and immediately received 46,000 Spanish dollars in compensation for the two prizes. Seeing the power of Decatur’s squadron, the bey decided not to fight, although he had a fleet and his capital was well protected.

Guerriere

,

Macedonian

,

Constellation

,

Ontario

,

Flambeau

, and

Spitfire

. The bey had violated Tunis’s treaty with the United States by allowing the British brig

Lyra

during the recent war to take two prizes belonging to the American privateer

Abellino

out of the Bay of Tunis to Malta and for allowing local merchants to obtain the contents of those ships much below their real value. Decatur demanded and immediately received 46,000 Spanish dollars in compensation for the two prizes. Seeing the power of Decatur’s squadron, the bey decided not to fight, although he had a fleet and his capital was well protected.

Decatur sailed next to Tripoli on August 2 to make a similar impression on its ruler, arriving in the harbor on August 5. The bashaw had allowed a British warship, the

Pauline

, to seize two more prizes of the

Albellino

, in violation of Tripoli’s neutrality, and take them to Malta, thus breaking the existing treaty with the United States. Decatur demanded 30,000 Spanish dollars. He and the bashaw finally settled on 25,000 and the release of ten Christian slaves. Two were Danes and eight Sicilians.

Pauline

, to seize two more prizes of the

Albellino

, in violation of Tripoli’s neutrality, and take them to Malta, thus breaking the existing treaty with the United States. Decatur demanded 30,000 Spanish dollars. He and the bashaw finally settled on 25,000 and the release of ten Christian slaves. Two were Danes and eight Sicilians.

Again wasting no time, Decatur left Tripoli on August 9 and stopped in Messina to release eight prisoners and then sailed for the Bay of Naples, arriving on September 8, where he was greeted warmly and thanked by the foreign minister and the king of the two Sicilies for obtaining the release of the prisoners. By this time Decatur had accomplished everything Madison wanted and then some, and he prepared to go home. He sent his squadron on ahead to rendezvous with Bainbridge at either the Spanish port of Malaga or Gibraltar. He then stood out alone from Naples on September 13 in the

Guerriere

and shaped a course for Gibraltar, expecting to meet Bainbridge.

Guerriere

and shaped a course for Gibraltar, expecting to meet Bainbridge.

On the way he spotted the Algerian fleet—seven warships: four frigates, and three sloops—sailing toward him. He cleared for action. But he warned the crew that the menacing ships ahead would have to fire first; America was now at peace with Algeria. If the Algerians fired, however, Decatur meant to take the lot of them. Tension lessened considerably aboard the

Guerriere

when the Algerians ran to the leeward side of the frigate, indicating they were not interested in a fight. For amusement, the Algerian admiral shouted to Decatur through a speaking trumpet, asking in Italian where he was going, and Decatur shouted back, “Where I please.” The Algerians sailed on, and Decatur maintained his course for Gibraltar.

Guerriere

when the Algerians ran to the leeward side of the frigate, indicating they were not interested in a fight. For amusement, the Algerian admiral shouted to Decatur through a speaking trumpet, asking in Italian where he was going, and Decatur shouted back, “Where I please.” The Algerians sailed on, and Decatur maintained his course for Gibraltar.

MEANWHILE, COMMODORE BAINBRIDGE, full of ambition, stood out from Boston on July 2 and arrived off Cartagena on August 5, traveling in the brandnew 74-gun

Independence

, the first ship of its size to sail under the American flag. The sloop of war

Erie

, the brig

Chippewa

, and the schooner

Lynx

made up the rest of Bainbridge’s squadron. The

Spark

and

Torch

from Decatur’s fleet were in port, and they informed Bainbridge of Decatur’s success against Algiers. None too pleased, Bainbridge changed his plans and decided to visit Tunis and Tripoli, only touching at Algiers on the way. He sailed from Cartagena on September 13 and visited Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli, exhibiting his powerful squadron, reinforcing the impression Decatur had made on the dey, bey, and bashaw. Bainbridge was sorely disappointed that Decatur had settled with all three states before he arrived, but the American consuls assured him that his appearance so soon after Decatur would have a lasting salutary effect on the rulers. Bainbridge wasn’t appeased.

Independence

, the first ship of its size to sail under the American flag. The sloop of war

Erie

, the brig

Chippewa

, and the schooner

Lynx

made up the rest of Bainbridge’s squadron. The

Spark

and

Torch

from Decatur’s fleet were in port, and they informed Bainbridge of Decatur’s success against Algiers. None too pleased, Bainbridge changed his plans and decided to visit Tunis and Tripoli, only touching at Algiers on the way. He sailed from Cartagena on September 13 and visited Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli, exhibiting his powerful squadron, reinforcing the impression Decatur had made on the dey, bey, and bashaw. Bainbridge was sorely disappointed that Decatur had settled with all three states before he arrived, but the American consuls assured him that his appearance so soon after Decatur would have a lasting salutary effect on the rulers. Bainbridge wasn’t appeased.

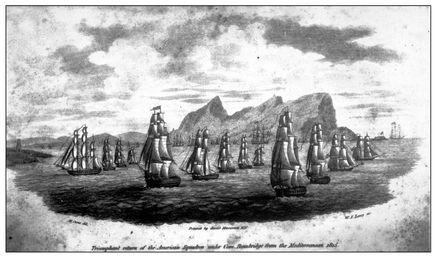

Figure 33.1: Michele Felice Cornè,

Triumphant Return of the American Squadron under Commodore Bainbridge from the Mediterranean, 1815

(courtesy of Naval Historical Center).

Triumphant Return of the American Squadron under Commodore Bainbridge from the Mediterranean, 1815

(courtesy of Naval Historical Center).

He set sail for Malaga, where the

United States

,

Enterprise

,

Boxer

,

Firefly

, and

Saranac

joined him. They had just arrived from the United States. Madison was making sure he had enough force in the Mediterranean to accomplish his goals. Secretary Crowninshield was even getting a third squadron ready to sail under Isaac Chauncey if good news did not come from either Decatur or Bainbridge.

United States

,

Enterprise

,

Boxer

,

Firefly

, and

Saranac

joined him. They had just arrived from the United States. Madison was making sure he had enough force in the Mediterranean to accomplish his goals. Secretary Crowninshield was even getting a third squadron ready to sail under Isaac Chauncey if good news did not come from either Decatur or Bainbridge.

In a few days Bainbridge sailed his entire fleet the short distance to Gibraltar to await Decatur’s arrival. On October 3, Decatur’s squadron arrived, except for the

Guerriere

and Decatur himself. Bainbridge had no way of knowing when Decatur would appear, so he made preparations to leave for the United States. On orders from Secretary Crowninshield, Bainbridge left a few ships in the Mediterranean to protect American interests. Captain John Shaw was in command of the new squadron with the

United States

, the

Constellation

, the

Ontario

, and the

Erie

. Bainbridge wrote to Shaw, “The object of leaving this force is to watch the conduct of the Barbary powers, particularly . . . Algiers.” The United States has had a naval presence in the Mediterranean ever since.

Guerriere

and Decatur himself. Bainbridge had no way of knowing when Decatur would appear, so he made preparations to leave for the United States. On orders from Secretary Crowninshield, Bainbridge left a few ships in the Mediterranean to protect American interests. Captain John Shaw was in command of the new squadron with the

United States

, the

Constellation

, the

Ontario

, and the

Erie

. Bainbridge wrote to Shaw, “The object of leaving this force is to watch the conduct of the Barbary powers, particularly . . . Algiers.” The United States has had a naval presence in the Mediterranean ever since.

Bainbridge stood out from Gibraltar on October 6, and as he was leaving the harbor, the

Guerriere

hove into view and saluted the

Independence

. Bainbridge returned the salute but kept right on going, apparently wishing to avoid meeting Decatur face-to-face. Not understanding what was going on, Decatur jumped into his gig and chased the

Independence

, caught her, and climbed aboard for a talk. He knew something was wrong when the

Independence

did not even slow down so that he could board, but he wasn’t quite prepared for the icily formal reception he got from Bainbridge, who apparently blamed Decatur personally for robbing him of his chance for glory. The meeting was short and awkward and irritated Decatur no end. There was nothing he could do about it, however. He returned to his frigate and sailed home alone, reaching New York on November 12 to receive a hero’s welcome, as he deserved.

Guerriere

hove into view and saluted the

Independence

. Bainbridge returned the salute but kept right on going, apparently wishing to avoid meeting Decatur face-to-face. Not understanding what was going on, Decatur jumped into his gig and chased the

Independence

, caught her, and climbed aboard for a talk. He knew something was wrong when the

Independence

did not even slow down so that he could board, but he wasn’t quite prepared for the icily formal reception he got from Bainbridge, who apparently blamed Decatur personally for robbing him of his chance for glory. The meeting was short and awkward and irritated Decatur no end. There was nothing he could do about it, however. He returned to his frigate and sailed home alone, reaching New York on November 12 to receive a hero’s welcome, as he deserved.

Decatur’s success underscored the need for a strong navy and helped build support in the country for a long-term commitment to bear the burden of a respectable defense force, all of which Madison hoped the Mediterranean mission would accomplish, beside ridding him of the Barbary pirate nuisance.

By moving a divided nation to agree that a strong navy and army would protect rather than undermine the Constitution, the horrific burdens of those who fought the war could ultimately be justified. And this new consensus on defense policy would in turn lay the foundation for a profound change in Anglo-American relations, further justifying the great sacrifices of the young soldiers and sailors.

CHAPTER THIRTY-FOUR

From Temporary Armistice to Lasting Peace: The Importance of the War

A

MERICANS WERE QUICK to forget the gross failures of their leaders during the war and the horror people felt in the fall of 1814, when it looked as if the fighting would continue. The country concentrated only on its successes. The amnesia served America well, as her people looked confidently to the future. A major component of this new confidence was the remarkable, totally unexpected political unity that arose immediately after the peace. Albert Gallatin wrote, “The war has renewed and reinstated the national feelings and character which the Revolution had given, and which were daily lessening. The people now have more general objects of attachment, with which their pride and political opinions are connected. They are more Americans; they feel and act more as a nation; and I hope that the permanency of the Union is thereby better secured.”

MERICANS WERE QUICK to forget the gross failures of their leaders during the war and the horror people felt in the fall of 1814, when it looked as if the fighting would continue. The country concentrated only on its successes. The amnesia served America well, as her people looked confidently to the future. A major component of this new confidence was the remarkable, totally unexpected political unity that arose immediately after the peace. Albert Gallatin wrote, “The war has renewed and reinstated the national feelings and character which the Revolution had given, and which were daily lessening. The people now have more general objects of attachment, with which their pride and political opinions are connected. They are more Americans; they feel and act more as a nation; and I hope that the permanency of the Union is thereby better secured.”

America’s newfound unity and her commitment to a strong military forced Europe to take her more seriously. Before the war, the United States was a big, prosperous country without military capacity. Now she was an incipient power that Britain and the other European imperialists could no longer treat lightly, as they had in the past. The Liverpool ministry’s cynical perpetuation of the war to expand British territory and dismember a rival had unintentionally amplified America’s maritime power. Instead of curbing a competitor, the British had markedly increased her strength.

As Castlereagh and his colleagues considered Britain’s North American policy going forward, the central question was whether to concede the growing power of the United States and reach an accommodation with her or to treat her as a rival and potential enemy, contesting her expansion and inviting conflict at every turn. The combination of a strong army and navy, sound fiscal underpinnings, and political unity in America led the foreign minister to adopt a policy of accommodation rather than confrontation. Liverpool endorsed the new approach, initiating a fundamental change in British policy that became the most important outcome of the War of 1812. It more than compensated for all the horrors borne by ordinary people in America, Canada, and Great Britain.

The reactionary Castlereagh had no love for the American republic; he was simply recognizing that given the new strength of the United States, it was in British interests to prevent their inevitable disagreements from turning lethal. He did all he could to remove barriers to cooperation and promote the peaceful settlement of disputes. And he brought Liverpool and the rest of the cabinet along with him. The British historian Charles K. Webster wrote that Castlereagh “was the first British statesman to recognize that the friendship of the United States was a major asset . . . , and to use in his relations with her a language that was neither superior nor intimidating.” An augury of things to come had been the Duke of Wellington (the new British ambassador in Paris) taking the unprecedented step of calling on American ambassador Crawford and congratulating him on the treaty of peace.

It took a considerable amount of time before the United States recognized the fundamental change in British policy. America’s leaders remained leery of London’s intentions. Madison, Monroe, Gallatin, Adams, Clay, and their colleagues would have to be shown by concrete action that a new relationship existed. They wanted one, of course—every administration since Washington had wanted it—but they were not expecting a basic change in British policy. For them, the most important question was: would Britain’s leaders finally accept the independence of the United States and treat her with respect? They had not in the past, and their attitude had eventually led to war. A change of the magnitude that Castlereagh envisioned appeared unlikely to an American leadership that for years had dealt with British ministries with wholly different attitudes.

Napoleon’s triumphal entry into Paris on March 20, 1815, so soon after the Treaty of Ghent, helped move Britain and America toward a new rapport. His appearance was not a surprise in London. For many weeks, Liverpool and his colleagues had worried about a military coup in Paris. Nonetheless, when the event happened, Liverpool had half his army in North America in the quixotic pursuit of more territory. That army was needed immediately in Flanders, but it would not be available for weeks. In that time Bonaparte could raise an immense army and become as big a menace as ever.

Immediately after seizing power, Napoleon tried to reassure the allies that he had changed, that his intentions were peaceful, but they were having none of it. When he entered Paris, the great powers unanimously committed themselves to destroying him before he got too strong. They were ready to bring their full weight to bear against him. Wellington was in Vienna at the time, and the powers looked to him to lead the coalition armies. He had to act fast, however. If Bonaparte were given sufficient time, he could raise an immense army and be hard to defeat. For Liverpool to have a large part of the British army in North America at this critical moment appeared the height of folly.

Other books

Deadly Bonds by Anne Marie Becker

With This Ring (Denim & Spurs Book 1) by Aliyah Burke

Foreigner by Robert J Sawyer

No Proper Lady by Isabel Cooper

Something to Hold by Katherine Schlick Noe

Love Lessons by Harmon, Kari Lee

The Edge of Desire by Stephanie Laurens

The Mistborn Trilogy by Brandon Sanderson

Scrappily Ever After by Mollie Cox Bryan

Blindsided by Katy Lee