A Curable Romantic (43 page)

Read A Curable Romantic Online

Authors: Joseph Skibell

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #Genre Fiction, #Historical, #Jewish, #Literary, #World Literature, #Historical Fiction, #Literary Fiction

“I’m astonished to hear you say such a thing,” I told him.

“Our science is young, Dr. Sammelsohn, and we’ve no idea where these procedures will lead us. Perhaps only when we’re done with the voyage will we know for certain where we have been. In any case, thank you for meeting me here tonight.”

Dr. Freud called for the waiter and instructed him to push two tables together. He next unrolled an enormous chart across the two tabletops. From his medical bag, he took out pens and bottles of ink, the sort medical illustrators use, and, from the inside pocket of his vest, a small quantity of scraps.

As he unfolded these, I saw that his handwriting covered both sides in chaotic fashion.

“Notes from another mad session,” he explained. “Tonight’s, in fact. Many of them concerning you.” He removed his coat and hung it on the back of his chair. “Let me just ink these in and I’ll explain everything to you at once.”

He bent over the chart and, consulting his notes, began filling in the data. I’d never seen him quite so excited. Pacing round the tables, the way an artist might a half-finished canvas, he slurped at his coffee without looking at the cup. His hair hung down in loose strands before his eyes. His tie was unknotted, his vest unbuttoned. Ink colored his fingers; and his cuffs, despite the precaution he took, were soon busy with stains.

“Waiter!” he cried again after a moment, standing back to judge his work. “Two more coffees, and make them strong — oh, and two snifters of brandy as well!”

Returning to the chart, he corrected some small slips of his pen with a chamois. The waiter brought our drinks, placing everything on a table nearby, his calm manner in direct contradiction to Dr. Freud’s agitation, an agitation that was proving contagious. I was trembling with nervousness myself.

“Given the depth of the psyche,” I said to Dr. Freud, “mightn’t it be preferable to remain blind to one’s former lives? Perhaps man is not meant to know himself quite so completely.”

Dr. Freud held his notes before his face and squinted to read them. “This isn’t the best place for this work, I’m afraid,” he said, moving closer to the lamp.

I continued, “If Heaven or happenstance or even human incuriosity sees fit to erect a curtain between who a man thinks he is and his deeper self, should a man really take advantage of a rip in the fabric to peek through that curtain?”

Dr. Freud grunted noncommittally.

“Mightn’t one be opening a Pandora’s box that could affect the course of one’s entire life?”

Dr. Freud glanced up, frowning like a man who’d bitten into an unripe lime. “Don’t be absurd, Dr. Sammelsohn,” he said, cleaning his pen with his tongue and drying it on his chamois, and instantly I felt that he was right. Only a man content with his own smallness would walk away from the Faustian bargain: isn’t knowledge of one’s true self worth losing everything, including one’s soul? and didn’t Dr. Faust beat the Devil in the end, simply by proclaiming his belief in God? or was it his belief in Christ?

If the former, I felt emboldened; if the latter, not as much.

Dr. Freud rolled down his sleeves and clipped his cufflinks through his cuffs. He buttoned his vest and laced the golden chain of his watch through the slits in its fabric. With a lighted cigar in his hand, he brushed back his hair. Raising two fingers to his lips as though he were about to whistle, he instead fixed the part in his mustache.

“Come. Let us have a look,” he said. “It’s a trifle inelegant perhaps, but it was the only way I could keep track of all the information Ita was spewing forth.”

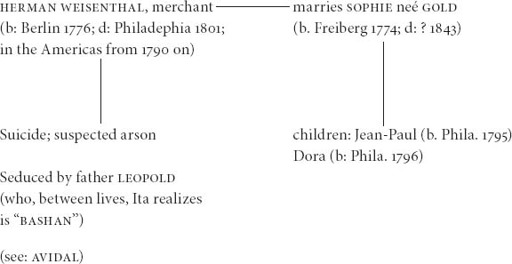

He and I bent over the chart spread out across the two tabletops. In scarlet ink, Dr. Freud had sketched in all the incarnations Ita had recalled, as though each were an entry in a genealogical record of a large family, with lines branching off from each persona to its relevant events and relationships.

For example:

In blue, he’d charted the incarnations of Zusha, Ita’s grandfather, who appeared now as her husband, now as her wife, now as her master, now as her lover, her owner, or her slave. Across the long plain of Jewish history, these two had shared a combustible relationship, taking turns murdering or being murdered by each other. Discovering each other in every life, one always taking the other by surprise, one always gaining the upper hand, neither seemed to realize that a person pays in the next life with his own for the lives he takes in this one.

Charted in green ink, my father (or his various incarnations) appeared periodically as well, always at a polite distance, always facilitating, through his ignorance, the meeting of these two incompatibles.

“Of course, the whole thing is necessarily simplified in this graphic form,” Dr. Freud told me. “Every detail is highly overdetermined.”

In gold, he’d documented the appearance and disappearance of a fortune Ita had spent all her lives chasing. Having earned it in one life, she’d lose it in the next, only to inherit it in another after Zusha had stolen it during a life in between. In a similar vein, in pink, Dr. Freud had traced a strain of syphilis Ita first contracted in the eleventh century from a parish priest. Dr. Freud cracked his knuckles and pointed at the chart. “Follow the chain of syphilis, Dr. Sammelsohn, and you’ll see that time and again, every few lives, Ita reinfects herself. It goes round and round in a configuration I can only describe, on this chart anyway, as a double helix.”

(Once again, as with the cocaine — but more on this below — a blind Freud had found his way to a treasure that, for whatever reason, he couldn’t see.)

Pointing with his pen, he brought my attention to other entries marked in red. “Look closely here, Dr. Sammelsohn, and you can see the amazing role fire seems to play in so many of lives.” He tapped his chart with an unlit cigar. “Here, as you can see, she destroys a country church, burning its congregants and its vicar to cinders, only to suffer the same cruel fate three-quarters of a century later as a burgher in the Alps. Here, she drowns her own children; there, a thousand years later, she is drowned. Here, she swindles; there, she is murdered by swindlers.”

lives.” He tapped his chart with an unlit cigar. “Here, as you can see, she destroys a country church, burning its congregants and its vicar to cinders, only to suffer the same cruel fate three-quarters of a century later as a burgher in the Alps. Here, she drowns her own children; there, a thousand years later, she is drowned. Here, she swindles; there, she is murdered by swindlers.”

“And what’s all this?” I said, pointing to various mathematical calculations littering the margins of the chart.

“Nothing, just nonsense,” Dr. Freud said, “just some details of each person’s nose and various notations concerning cycles of twenty-three and twenty-eight, information I’d gathered in the hopes of enticing Wilhelm’s interest in the project, but I’m sorry to say he considers the work beneath his scientific dignity, and I’ve come to doubt the data is of more than dubious value.”

I could feel Dr. Freud watching me.

“You’re looking for yourself, of course,” he said.

“Of course,” I admitted.

“Yes, but, you see, I’ve intentionally left

you

, as an item, off.”

“And why is that?”

“So that, having arranged to meet you here tonight, I might show you the chart and consult with you upon its meaning without compromising your medical objectivity. Your collaboration is proving far too precious for me to render its potency null by implicating you into the equation. Tonight, after you’ve taken a look, I’ll go home and fill in the rest. I have only to ink in the matters pertaining to you. I possess a certain amount of information about where you, or more precisely your soul, has been for the last few thousand years.”

“But …” I could only protest.

“Also,” Dr. Freud said, stopping me, “I’m not certain at this point how much of this information I can share with you without violating Ita’s confidentiality, to say nothing of Fräulein Eckstein’s.”

“Of course,” I said. Once again, I’d underestimated Dr. Freud’s integrity, and once again, he’d proven me deficient in my esteem for him. Here was a man of unbending medical scruple, of unfailing principle, or so I thought until, unable to constrain himself, he said, “Oh, what the deuce! It’s really too exciting to keep to oneself — and who else, other than Minna, can I discuss it with?” He spoke in a rush, hurriedly inking in all the data that pertained to me. “Marty takes no interest in these things. The sexual component of my work disgusts her. She’s a lovely woman, and a man couldn’t ask for a better mate, although that’s the problem with a perfect wife, isn’t it? It’s impossible to divorce her! Ha! Upon what grounds? You see? There are none!”

Wiping the nib of his pen, he pinned me with his gaze. “Now we must clear our heads for the great work that lies before us. Mankind, I’m certain, is not yet prepared to accept the gift I’m on the point of bestowing upon it: the truth about our many lives and the effects each has upon those that follow. You shall be my test case, my first audience, Dr. Sammelsohn. Come,” he said, leaning in. “The chart is complete and, for the moment, up to date. Now tell me what you think.”

He pointed with the two fingers that held his burning cigar.

“Here,” he said. “Look here. This is a most important thing. You see this cinnamon-colored line I’ve only just inked in?” He directed my attention to a long golden-brown ribbon of ink that, as a dotted line, spiraled though the various stages of Ita’s long trek.

“I see it,” I said, bending nearer, “though the light is rather poor. However, what does it represent?”

“Love.” Dr. Freud grinned mischievously. “Real, actual, consummated, mutual, fructifying, and revivifying love. But as you can see, my dear young man, the line is segmented and broken. Nowhere on the chart is it complete. Follow its path and you’ll come to realize what I have realized these last few weeks working with our friend. Though in each of her many lives, Ita experienced a profound longing for another — that person appearing on my chart in amethyst — the timing of these encounters has never been right, was, in fact, almost always horribly wrong, and decisively so — off sometimes by a few days, sometimes by hours, sometimes by entire centuries. Here, for example, as a fuller’s apprentice in Babylon, she’s conceived a passion for her master’s wife that is never consummated. Seven hundred years later” — he pointed to the bottom of the chart — ” we find that same soul, as a young page, pining for a knight who has no interest in him, except as a convenient source for an occasional moment of sexual gratification.”

“I’m the fuller’s wife?”

“And the page. Again and again, through the millennia, the theme plays itself out in a thousand different variations. In each life, circumstances throw you together, and, in each life, fate keeps you from merging.”

“And Ita knows all this?”

“In part, but only in part. And that’s why she has been so insistent upon consummating your marriage. No longer can we imagine her the disappointed bride of a single night. Alas, she has been hungering for you over the course of many thousands of years.” Dr. Freud pointed to the top of the first page. “Almost as far back as it goes, days before the giving of the Torah at Mt. Sinai, actually, when Moses separated the men from the women, you and she, newly liberated from your slavery in Egypt,

made plans for a clandestine rendezvous. You were to meet her in her tent. Although I should say ‘meet him in

his

tent,’ for as you can see, in this encounter, she was the male” — he pointed to an ancient-sounding name inscribed upon the chart in scarlet — “yourself the female.” Another name in purple. “Fearful of breaking the prophetic law, you avoided her that night and for many nights thereafter. Alas, she seems to have been among the scoundrels committing sexual revelry at the base of the Golden Calf, all of whom, as you know, were subsequently slaughtered by the Leviim, along with Moses.”

“

Along with Moses?

” I said.

“Hm, they slaughtered him as well.” Dr. Freud looked through the scraps of his notes. “Or I believe that’s what Ita told me. She was an eyewitness, after all. However, since then, it’s been the same thing over and over again. Perhaps even as paramecia, you two couldn’t quite come together.”

“And if I choose to consummate my marriage with her now?”

“To liberate Fräulein Eckstein or something like that?”

“And Ita and myself.”

“Break the long chain of karma, to quote Fräulein Eckstein’s brother?”

“Yes, certainly.”

“Well.” Dr. Freud swallowed the last of his brandy. “You would be doing several things at once: primarily, you would be stealing from me the most important patient and the most essential case I’ve yet to encounter in all my researches; and for that reason alone, I cannot permit it. Secondly, can we really trust Ita to make good her promises? I think not. Further, who knows what might happen if, after thousands of years, you two consummate your love? The entire city might burn up in the conflagration! And lastly, there’s a concern about what the sexual act with Ita, perpetrated through the vile use of Fräulein Eckstein, might do to Fräulein Eckstein, for whose care, as I’ve never ceased to remind you, I remain responsible.”