A History of China (16 page)

Read A History of China Online

Authors: Morris Rossabi

EVELOPMENT OF THE

Q

IN

S

TATE

The Qin capitalized on the changes in the late Zhou to become sufficiently dominant for its fame to spread as far away as the Hellenistic and Roman worlds. The warfare of the late Zhou era resulted in the displacement of “feudal” nobles by professional military men, the rise of infantry rather than the cumbersome and clumsy war chariots, and the development of the crossbow, which led to the use of mounted archers and the integration of cavalry into the military. It also fostered the centralization of states, the decline of the “feudal” nobility, the emergence of the

shi

and a new landlord class (which was not part of the old nobility) to positions of power, the rise of professional administrators (the ancestors of the scholar-officials of later eras), and the growth of local administrative units controlled by the central state authorities.

A different pattern of land distribution emerged, with peasant owners and landlords having obligations to the state rather than to “feudal” lords. Agricultural production increased, as did population; and, with somewhat more prosperous conditions, commerce (particularly in luxury products) grew and some merchants accumulated considerable fortunes. The new schools of thought that developed during this time complemented these political, economic, and social developments by asserting that (1) rulers and officials ought to be chosen because of their own qualifications, not because of the accident of birth, (2) individuals needed to perform the tasks incumbent on their social status, and (3) political unity and a shared cultural identity were essential for social stability. Qin was probably the first Chinese state to promote these changes and proved to be the initial beneficiary of these successful transformations.

First based in the modern province of Gansu, Qin arose on the fringes of the Zhou dynasty. It confronted hostile non-Chinese groups, which compelled its rulers to maintain a large military force. Frequent battles with a group known as the Rong offered the Qin military experience and resulted, by the mid fourth century

BCE

, in the creation of the best army among the Chinese states. The reforms advocated by the Lord of Shang, the Legalist thinker, bolstered the strength of the state. Seeking to undermine the power of the local lords, the Lord of Shang organized the state into thirty-one counties, each governed by a centrally appointed official who was, in turn, under the administrators in the capital at Xianyang, on the outskirts of the modern city of Xian. Simultaneously, he encouraged the dispersal of land ownership to the peasants, reducing further the authority and property of the “feudal” lords. Conceiving of agriculture and warfare as basic pursuits, he promoted the interests of the peasantry and the military while imposing restrictions on merchants and artisans who, he perceived, played a lesser role in the economy and the state. Partly to regularize and facilitate economic transactions and partly to protect gullible peasants and consumers, he standardized weights and measures within the state. As befits his allegiance to Legalism, he stressed well-publicized laws by which everyone, even the most prominent and powerful, would be judged. Punishments for infractions were severe, but rewards (e.g. for meritorious military service and production of more than the quota of tax in kind) included lavish inducements such as exemption from labor service and the granting of honorary titles. Bestowals of these honorary ranks naturally diminished the value of the old “feudal” titles – still another means of subverting the position of the “feudal” nobles.

The Lord of Shang’s reforms paved the way for Qin success, although the state’s final victory was due to the mobility of its forces and its ability to impose strict discipline on them. The Lord of Shang’s influence initiated Qin’s drive toward centralizing China, but the pace of expansion quickened about one hundred years after his death in 338

BCE

. Qin destroyed the Zhou dynasty only in 256

BCE

, and then from 230 to 221 overwhelmed, in rapid succession, the states of Han, Zhao, Yan, Wei, Chu, and Qi. Within a decade, Qin conquered and then annexed the lands of its principal rivals. By 221, its leader had become the uncontested ruler of a mostly centralized China. Scholars have attributed Qin’s victory first to geographical happenstance. Its base in western China was protected by three mountains, which were well guarded, enabling its leaders to have few concerns about external attacks. Geographic isolation also permitted Qin to avert the traditionalism of the central states and to be more receptive to new and more effective practices and institutions. Its struggles with so-called barbarians strengthened its military and gave primacy to martial virtues and discipline. Its emphasis on agriculture resulted in more technological innovations and ingenious irrigation works that increased output. These irrigation complexes, a few of which have survived to the present day, enriched the state. The highly centralized government, the tightly controlled administrative machinery, the uniform laws, and the influence of Legalist principles concerning a powerful state (enriched by promotion of agriculture) offer the likeliest explanations for its triumph.

Probably just as critical was Qin’s willingness to accept the assistance of people from beyond its borders, which set a precedent for future dynasties. For example, the non-Chinese who would from time to time subjugate and then rule China throughout Chinese history could not have succeeded without recruiting talented Chinese counselors. Such foreign rulers generally constituted a small population compared to the Chinese and required the assistance of the Chinese in administration and governing. Like the later non-Chinese dynasties, the Qin, which originally lay outside the Chinese cultural sphere (although its people were ethnically Chinese), needed and obtained assistance from outsiders. Lü Buwei (291?–235

BCE

), an extremely wealthy merchant, arrived in Qin just at the beginning of its final phase of expansion. Serving as a court adviser for several decades, he also turned over his concubine, who may already have been pregnant, as a wife to the Qin ruler, who believed the child was his and accepted him as his successor. This child grew up to become the first emperor of China. Li Si (ca. 280–208

BCE)

, another Chinese, proved to be the this emperor’s most trusted adviser and engineered many of the most important policies promulgated by the Qin.

Centralization and standardization were the keynotes of these policies. Adopting Li Si’s suggestions, the Qin rulers abolished the old “feudal” states and instead adapted their own administrative machinery to the newly subjugated territories. Dividing the country into thirty-six commanderies, with each composed of a number of counties, they placed centrally appointed and paid officials in charge of local government. To avert the meddling of the formerly powerful elites, the court moved many of them to Xianyang, providing them with suitable accommodation and stipends. Centralization of local regions was accompanied by concentration of power in the hands of the Qin ruler, who now sought a title that differed from and appeared superior to the Zhou designation of “king.” The eventual choice of the title “Huangdi” (Yellow Emperor) was inspired because

di

designated the Shang dynasty’s deity and had religious and political associations with the Zhou as well. The title, with its reverberations of a glorious heritage, provided the new dynasty with the majesty and legitimacy it sought. The Qin ruler who united China, a charismatic and dominant figure, assumed the title of Shi Huangdi (“First Emperor,” r. 246–210

BCE

) and established the first empire in the Chinese tradition. To encourage even greater centralization, he imposed the Qin state’s legal code, with its emphasis on group responsibility for individual crimes and on harsh punishments (though not markedly more severe than those the Zhou states imposed), on the entire country.

Such policies subverted the authority and sometimes resulted in the dispossession of the old local aristocracy. Seeking to prevent a resurgence of localism, the Qin thus alienated and, in a sense, created potential enemies. Its bias against commerce, in addition, fostered opposition from merchants. The Qin’s perhaps overly radical program and its enthusiastic implementation of these policies drew the hostility of influential groups who no doubt awaited an opportunity to reassert their lost claims to power.

IN

A

CHIEVEMENTS

Partly to bolster his legitimacy in the face of such opposition but also to foster centralization and standardization, the First Emperor organized mammoth building projects. The most important such enterprise was the construction of the so-called Great Wall (which ought not to be confused with the present Great Wall, most of which dates from the sixteenth century), designed to protect against incursions by the non-Chinese steppe peoples residing north of China. Chinese sources may have exaggerated the expanse and length of the Wall and may have omitted the fact that part of the construction merely entailed merging and repairing walls already built by the individual states during the seemingly incessant warfare that afflicted the late Zhou period. Nonetheless, whatever the overstatements, considerable effort and resources were devoted to this enterprise. Although scholars have questioned the Wall’s value as a deterrent, it was surely an expensive project. The sources indicate that 300,000 workers labored on the construction, and the number of fatalities was high. Forced labor was required on still another of the First Emperor’s projects, the construction of roads. He ordered Meng Tian (d. 210

BCE

), a leading general who also supervised the Great Wall project, to build a five-hundred-mile highway stretching from Xianyang to an area in modern Inner Mongolia within the confines of the Wall. He also promoted the construction of other roads radiating from Xianyang, which naturally facilitated centralized control and the movement of Qin armies while simultaneously fostering commerce. Large numbers of laborers were assigned to these road-building efforts. Similarly, many peasants were forced to migrate to the capital to construct elaborate palaces for the old aristocratic families and for the emperors. Seeking a more grandiose palace than the one from which his predecessors ruled, the First Emperor recruited even more laborers to build a new residence and a hall for court affairs south of the Wei river.

Figure 3.1

Terracotta Warriors, Xian, Shaanxi, China. © Jon Arnold Images Ltd / Alamy

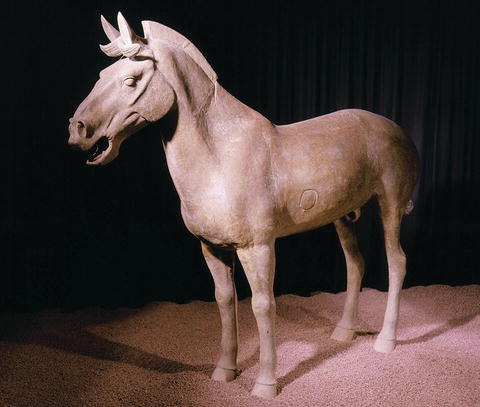

Figure 3.2

Horse, terracotta figure from tomb of Qin Shi Huangdi, 221–210

BCE

, emperor of China, Qin dynasty, 221–207

BCE

, from Lintong, Shaanxi province, China. Discovered 1974. © The Art Archive / Alamy

Like the Egyptian pharaohs, the First Emperor began almost as soon as he acceded to the throne to prepare for his death and to create a suitable burial place. He was probably eager to fashion an awe-inspiring and majestic structure as a means of bolstering his own and his descendants’ legitimacy. The tumulus that began to be built in the last years of his reign was indeed imposing. Although it still has not been excavated, literary sources reveal that its interior was stocked with precious valuables from all parts of the empire and was encircled by pools of mercury and ceilings. The walls and floors were lined with depictions of the sky and Heaven and of the lands the Qin ruled. Eventually, when the emperor died, several of his concubines joined him in death. Some of the unfortunate laborers were also entombed in order to prevent them from telling potential grave robbers about safe passageways into the tumulus (in addition, these passageways were guarded by elaborate death traps to deter such tampering). The 1974 discovery of an adjacent site confirmed the painstaking, expensive, and monumental plans for this burial location. In the vault was discovered an “army” of more than seven thousand life-size terra-cotta statues built to defend the tumulus, accompanied by statues of horses, bronze chariots, and weapons. Such a massive project necessitated the use of large numbers of corvée laborers, most of whom had to leave their homelands for long periods of time and many of whom perished as a result of their arduous labor and the unsanitary conditions.