A History of China (15 page)

Read A History of China Online

Authors: Morris Rossabi

Although some of the poems offer trenchant or, on occasion, covert critiques of Zhou society, many appear to be straightforward evocations of hopes, wishes, and reality. Some are exactly what they purport to be, with no symbolic or hidden messages. They include courtship poems, songs of lovesick or neglected young men or women, and verses reflecting the woes of disillusioned and abused wives. These poems are direct and unencumbered with larger political or social meanings.

However, because the compilation of the

Book of Odes

was often attributed to Confucius, individual poems have been accorded a moral or didactic interpretation. One traditional view was that Confucius selected the three hundred poems from a larger anthology while another was that he simply gave his imprimatur to an existing collection. Whatever the true origin of the poems, Confucius emphasized their significance in the education of a gentleman. According to the

Analects

, he urged his disciples to study the

Odes

in order to broaden their sensibilities, refine their language, and enlarge their knowledge of nature. He insisted that officials needed to be conversant with the

Odes

because others made repeated references to them when discussing and negotiating state affairs. Because many officials had memorized the poems, could allude to them, and accepted the rather labored and exaggerated interpretations of individual songs, Confucius advised his disciples to ponder and seek to understand the

Odes

for the very practical reason of fulfilling their public roles and responsibilities. Additional evidence that Confucius played a role in the compilation or editing of the work is the large number of hymns deriving from the state of Lu, his native land.

Confucius is also credited with amassing the various passages that constituted another of the Five Classics, the

Book of Documents

(

Shujing

). However, some sections of the work date from after Confucius’s death. A text written in archaic language, the

Book of Documents

consists of legendary, semihistorical, and historical passages with no underlying unity or at least little effort to produce a coherent narrative. Much of the text is composed of speeches. Since the writers or historians could not have been present during most of these discourses, the speeches cannot be considered authentic, although they may, on occasion, convey the general sense of what transpired. The parts of the work that deal with the Zhou dynasty are more reliable than descriptions of much earlier, semilegendary figures. Although many of the speeches and incidents cannot be attested, they nonetheless reveal the general themes and values that the compiler(s) wished to inculcate.

The most important of these themes was the Mandate of Heaven theory, which, according to the

Documents

, the early Zhou rulers expounded to Shang citizens whom they had just conquered. In seeking to justify the overthrow of the Shang kings, the Zhou leaders, in particular the Duke of Zhou, explained that Heaven, an amorphous force that controlled the Earth, bestowed a specific leader or group with a mandate to rule. As long as these designated rulers and their descendants continued to govern virtuously, they would retain Heaven’s support. Should they, however, abandon virtue and encourage corruption and exploitation, Heaven would retract its mandate, offering it instead to a new leader or group. How would one discover Heaven’s displeasure? If the new leaders emerged victorious, Heaven had surely bestowed its favor on them; here pragmatism merged with morality. In sum, each successive leader needed to prove himself morally fit to maintain the mandate, for Heaven did not grant the throne to descendants in perpetuity. The Zhou rulers asserted that their own overthrow of the Shang, which had lost the mandate, was thus justified. The

Documents

, in this way, contributed to a historical tradition of portraying the first rulers of a dynasty as honest, benevolent, and courageous and the last rulers as evil and immoral. New dynasties could therefore justify their usurpation of the throne. The implication was that no dynasty lasted forever.

In addition to the Mandate of Heaven theory, the

Documents

offers a specific and unusual view of the transfer of power. The text lauds legendary figures who selected the most meritorious candidate to succeed them instead of turning authority over to their sons. The mythical ruler Yao, for example, did not tap his son as his successor but rather chose a commoner named Shun. In turn, Shun handed over power to his minister Yu, not to any of his own progeny. Eventually, the principle of family succession, usually father to son, took hold, and the

Documents

ultimately confirm this mode of transfer of authority. Yet, considering the prestige accorded to the

Documents

, it is puzzling that the value of family seems to be superseded in these early examples. One explanation is that the work reflects the views and aspirations of the traveling group of philosophers during Confucius’s time. Deriving from nonelite backgrounds, they attempted to secure positions in government. Using the

Documents

, they could show that the legendary revered heroes of the past had selected successors on the basis of merit, not heredity. The lesson would presumably not have been lost on the contemporary rulers from whom they requested employment.

ECULARIZATION OF

A

RTS

Despite the political decentralization and weakness of the Western Zhou, its cultural achievements were not negligible and indeed paved the way for the efflorescence of the Eastern Zhou. Although Zhou bronzes initially resembled Shang models in technique and decoration, the weapons and ritual vessels now had inscriptions. As the number of bronze workshops increased, the vessels fashioned at these centers were no longer exclusively used for rituals. Output grew rapidly, and the more bronzes that were produced, the less well decorated and more secular they became. As a result, they were not a monopoly of the aristocracy. The Zhou decorations began to differ from those of the Shang. The shapes became less complex, and different animal forms were rarely combined to depict the legendary animals of the Shang. The vessels no longer portrayed the grotesque

taotie

mask, and some represented animals and particularly birds (which were now frequently depicted) in a much more naturalistic style than during the Shang.

Basic changes in decoration reveal even more clearly the transformation from Shang to Zhou thought and attitudes. These changes mirror the development in Yangshao pottery decorations from realistic portraits of animals and fish to more geometric conceptions. The animal forms in Zhou bronzes similarly turned away from realism to abstraction. At the same time, the Zhou bronzes show a greater emphasis on decorative designs. This focus on decoration may reflect a changing societal conception of the bronzes, which now had a wider and more secular audience. Instead of bronzes being produced for court rituals and awe-inspiring purposes as in the Shang, the Western Zhou bronzes were often used for ordinary occasions, eroding their evocation of majesty and their religious functions. The inscribed bronzes also indicated that the Zhou elite had them cast to commemorate significant events (victory in battle, marriage, etc.) or to communicate with the ancestors. They thus offer valuable data that supplement knowledge of the dynasty. Most inscriptions start with precise indications of the date and location, contributing to their historical value. They then describe a particular activity – a military campaign, a sacrifice, the investiture of an official, or an alliance. However, the number of divinations mentioned diminished, implying a change in attitude about direct spiritual or ancestral involvement in human affairs. Decorative objects that had little ritual significance (such as bronze mirrors and belt buckles) were often produced, and some imitated the “animal-style art” of the nomadic pastoral peoples who dealt with the Chinese.

The religious attitudes of the Western and later Eastern Zhou elite diverged from those of the Shang. Earlier beliefs centered on a variety of coequal divinities associated with nature, with Di represented as the dominant figure. The Western Zhou supplanted Di with Tian (Heaven), vital for the concept of the Mandate of Heaven, and tended to deemphasize animal and nature deities. Proper performance of ancestral rituals became at least as significant as obeisance to deities. Another indication of increasing secularism entailed transformations in the tombs. Human and animal sacrifices at burial sites diminished considerably. At these same tombs, various jade objects were buried with prominent individuals.

Bi

discs, symbolizing Heaven, as well as jade artifacts representing Earth and jade plugs for the openings of the deceased’s body to protect it from harm, served as important mortuary pieces. Later, in the Han dynasty, the custom of using jade to protect the body of the dead reached its height with the creation of elaborate jade suits for members of the elite. However, not all jades were designed as mortuary objects; many were fashioned as ornaments.

Despite its glorious philosophical, literary, and artistic masterpieces, the Zhou dynasty encountered difficulties in its last years. The Warring States era, with no centralized government, needed economic and political changes. Standardized currency and writing systems, regular taxes on agriculture and commerce, a local and regional administration that ensured safety and security and basic restraints on the seemingly all-powerful nobility, and a policy for dealing with occasionally obstreperous foreigners on China’s northern frontiers were required for greater stability and peace. The victory of one of the Warring States and the resulting unification and centralization of China brought about such a transformation.

OTES

1

Burton Watson, trans.,

Chuang Tzu: Basic Writings

(New York: Columbia University Press, 1996 ), p. 95 .

URTHER READING

Roger Ames, trans.,

Sun-tzu: The Art of Warfare

(New York: Ballantine Books, 1993 ).

Roger Ames,

Analects of Confucius: A Philosophical Translation

(New York: Ballantine Books, 1998 ).

Hsu Cho-yun,

Ancient China in Transition

(Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1965 ).

Victor Mair, trans.,

Tao-te-ching

(New York: Bantam Books, 1990 ).

Benjamin Schwartz,

The World of Thought in Ancient China

(Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1980 ).

Burton Watson,

The Tso Chuan

(New York: Columbia University Press, 1989 ). Burton Watson’s translations of classic philosophic and literary texts are invaluable for the general reader. See his

Han Feizi: Basic Writings

,

Zhuangzi: Basic Writings

,

Xunzi: Basic Writings

, and

Mozi: Basic Writings

(New York: Columbia University Press, 2003 ).

T

HE

F

IRST

C

HINESE

E

MPIRES

,

221 BCE–220 CE

Qin Achievements

Failures of the Qin

Han and New Institutions

Han Foreign Relations

Emperor Wu’s Domestic Policies and Their Ramifications

Wang Mang: Reformer or Usurper?

Restoration of a Weaker Han Dynasty

Spiritual and Philosophical Developments in the Han

Han Literature and Art

I

T

is perhaps trite to observe that certain short-lived periods represent vital watersheds in civilizations and provide essential structures for later glorious eras. The Qin dynasty (221–207

BCE

), with its brevity, exemplifies this assertion. It marked the transition from a China of small kingdoms and petty states to a China of great empires. The first Qin ruler was the first emperor of China. He and his principal ministers developed institutions that laid the foundations for centralization and were adapted and adopted by later dynasties. Traditional accounts have castigated the dynasty for its cruelty and its authoritarianism. However, any rulers would surely have had to use force to impose one government on the fractious political entities of the Warring States period. The Qin was doubtless more ruthless in its policies, but domination over the “feudal” lords, the aristocratic families, and the

shi

could not have been accomplished without violence. The Legalist rulers of the Qin were enthusiastic advocates of force in attaining their objectives and thus aroused the hostility of the previously powerful families, who eventually allied with military commanders to overthrow them.

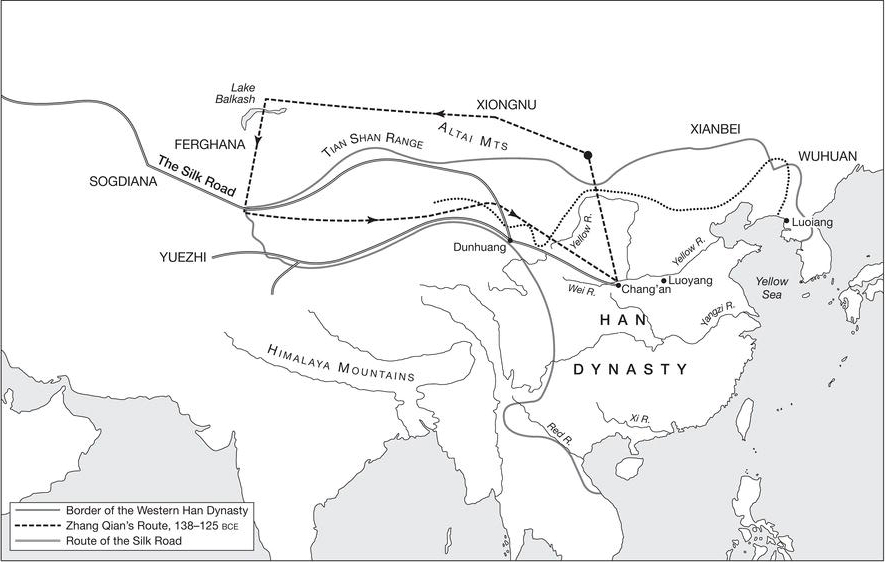

Map 3.1

Western (or Former) Han Dynasty

Having governed China for less than two decades, the Qin rulers scarcely had the time or resources to record the history of their own achievements. Instead, their successors in the Han dynasty shaped later Chinese perceptions of the Qin. Sima Qian (ca. 145–ca. 86

BCE

), the author of the

Shiji

(

Records of the Grand Historian of China

), offered the principal written account of Qin history. Though he was one of China’s greatest historians, he lived less than a century after the defeat of the Qin and was bound to reflect Han antagonism toward its rival. The reader should thus bear in mind that Chinese sources tend to magnify the Qin’s nefariousness though they often acknowledge, if somewhat half-heartedly, its considerable achievements.