A History of China (81 page)

Read A History of China Online

Authors: Morris Rossabi

The grain shortages that resulted from such falsifications and evasions were catastrophic. Power was often in the hands of the mess hall’s kitchen personnel because they determined who would get the life-saving food. Many dissidents who opposed these policies were beaten, tortured, or killed. Events spun out of control, and, on occasion, local officials themselves were blamed for the disasters and severely punished. Famines struck many rural areas, leading to an untold number of deaths by starvation. There were reports of cannibalism in some areas in the countryside. Many children died, and parents sold, abandoned, or, in extreme cases, murdered their children. Cadres had some access to food and gorged themselves when they had meetings or seminars. Trafficking in women, who sought to survive through prostitution, increased. The Communist Party blamed some of the agricultural failures on a series of natural disasters, which also resulted in casualties. It scarcely mentioned deficiencies in policies or mistakes in implementation. Those who challenged the party’s views and criticized specific government policies as contributing to famines were themselves criticized. For example, Peng Dehuai, the minister of defense and a great military hero, pointed to the failures of the Great Leap Forward. Although Mao, as one of the principal architects of the radical policies, was on the defensive, he was still able to stave off this critique at a major meeting in Lushan in August of 1959 and gained sufficient support to oust Peng from his position.

Conditions in the minority nationality border areas echoed the chaos in the central part of China. The radical policies of the Great Leap Forward increased the pressure on the minority nationalities to learn Chinese, to deemphasize their ethnic distinctiveness, and to detach themselves from their religions. Communization of animals and land and the propaganda against Islam prompted about sixty thousand Kazakhs in Xinjiang to flee to the USSR – an embarrassment in light of the Sino–Soviet dispute. Tibet proved to be even more of a challenge. In 1959, Tibetan Buddhist monks (assisted by foreigners) initiated a revolt. A Chinese army suppressed the revolt, but, accompanied by a contingent of Tibetans, the Dalai Lama departed and reached Dharamsala in north India, where he has remained since. India itself became involved in a territorial dispute. Within a few months in 1962, China emerged victorious, though tensions along the border remained.

ETURN TO

P

RAGMATISM

Despite this victory, Mao was in a weaker position because of the Great Leap Forward’s failures, and this offered more moderate leaders greater opportunities to shape policy. Liu Shaoqi (1898–1969; the head of state from 1959 to 1966), Deng Xiaoping (1904–1997), and other of their associates, many of whom had been trained abroad, denounced the Great Leap Forward and sought a return to a careful and planned economy. By 1960, Mao was apparently somewhat in retreat from his dominant position and from the Great Leap Forward, which he had earlier championed. The chaotic Great Leap Forward policy, which had resulted in the deaths of millions of people and had exposed incompetent and corrupt cadres, had aroused considerable opposition, and the opponents wanted a steadier course for society. These opponents, including Liu Shaoqi, began to demand more accurate and less inflated economic statistics and sought to root out cadres involved in nefarious activities or those who capitalized on their positions to make substantial profits. The moderates took command of the economy and then ordered the closure of the backyard steel furnaces and other experiments designed to promote self-reliance. These enterprises had simply squandered local resources. The moderates were especially concerned about the food supply and adopted a pragmatic policy to raise production. They dismantled or reduced the size of some communes, allowed peasants to have larger private plots of land, and offered farmers greater incentives to produce more and to sell their goods for their own gain. The new policy turned out to be successful, as more food reached the government and the markets. Mao appeared to have accepted moderation in the economy and ideology. Yet this turned out to be a period of quiet before the storm. Whatever additional capital was available was invested in state-owned industrial enterprises.

Moderation was, in part, subverted by foreign relations. The US involvement in Vietnam, which shared a border with China, had been initiated with the dispatch of an advisory military force to South Vietnam in the early 1960s to ward off North Vietnam. In August of 1964, an alleged naval confrontation between the USA and Vietnam, which proved to be fraudulent but served the interests of American policy makers who sought to intervene to help South Vietnam, prompted a buildup of US forces, which culminated in the arrival of half a million men in the south by 1965. Some US government officials attributed the conflict in Vietnam to China, referring to a domino effect in which the Chinese communists, who reputedly dominated North Vietnam, would first seek to conquer South Vietnam and then all of Southeast Asia. This interpretation and the assumptions underlying it were ahistorical. China and Vietnam had traditionally been hostile. Several dynasties in China had attempted to conquer Vietnam and had been rebuffed. There was no love lost between the two, and communist China did not dictate policy or strategy to North Vietnam. Yet this fallacious interpretation caused the USA to send troops to block the communist empire from overwhelming Southeast Asia. The Chinese communists viewed this sizable contingent of US forces not far from its borders as a clear threat. The USA’s support for Taiwan had already angered Mao. Now the USA, with massive firepower and with bombing of sites in North Vietnam, was intervening in a war virtually on China’s doorstep. Mao perceived the US involvement as a deliberate provocation.

N

I

SOLATED

C

HINA

The escalation of the Sino–Soviet dispute exacerbated China’s concerns. Conflicts between the two heightened throughout the 1960s. Insults were hurled back and forth between the erstwhile allies. Soviet leaders repeatedly condemned the Chinese communists for their radicalism and their unwillingness to work within the boundaries of the established world order. The Chinese communists distrusted and disdained dialogue and possible collaboration with the capitalist countries. In turn, they portrayed Soviet policy makers as “capitalist roaders” and as betrayers of Marxism for seeking to cooperate with the West. Government-controlled media produced scathing analyses of the Soviets’ acquiescence to the capitalist world.

This open breach with the USSR led to the final withdrawal of Russian technical experts and advisers and of Soviet economic assistance. Chinese leaders could no longer rely on trade for products it needed from the USSR. Assistance from or trade with the Soviet bloc in Eastern Europe also diminished and, in some cases, ended. Ideological disputes with the USSR translated into territorial conflicts. During the honeymoon period in Sino–Soviet relations, boundary disagreements had not surfaced, though there certainly were numerous potential problems. The 1689 Nerchinsk Treaty had been relatively equitable in border delineation, but the mid-nineteenth-century tsarist court and its officials in Siberia, capitalizing on China’s military weakness, had encroached upon Chinese territories and compelled Chinese officials to sign treaties turning the lands along the border with Manchuria over to Russia. After the Second World War, the USSR had assisted Mongolia in breaking away from China and establishing a sovereign country. In 1950, China had reluctantly abandoned claims to Mongolia, but it had not formally acquiesced to the mid-nineteenth-century so-called unequal treaties that had been forced upon the Qing dynasty and entailed loss of territory and sovereignty. As tensions in the Sino–Soviet dispute heightened, the potential for violence increased, and claims to land became prominent. Both sides amassed substantial numbers of soldiers along their frontiers, and Mongolia, under pressure from the USSR, permitted more than 100,000 Soviet troops to be stationed along its borders with China.

The Chinese communist leaders now faced 500,000 US troops in South Vietnam and at least as many Soviet forces along China’s northern borders. China had no allies among the major powers in the world. It distrusted Japan, which was, in any event, allied with the West, and it had just fought a successful war with India along its frontiers. In 1964, Indonesia had engaged in a purge of so-called communists, many of them its Chinese citizens. China’s ties with many African states had become frayed, and much of the Middle East, ruled by dictators or monarchs, feared the Marxist message.

Mao himself had become disenchanted with the moderate and incremental policies of the early 1960s, which were implemented by bureaucrats, intellectuals, and experts. Cloistered in his compound in Beijing and perhaps embittered by the failure of the Great Leap Forward and the communization movement and the ensuing loss of prestige, Mao planned new policies to challenge the status quo. He wanted to restore his tarnished image and, as a first step, in 1962 he initiated a Socialist Education Campaign to eliminate “reactionary” elements from politics, the economy, organizations, and ideology. At the same time, he began to develop a Stalin-style cult of personality. First, the government issued

Quotations from Chairman Mao Zedong

(

Mao zhuxi yulu

, later known as “The Little Red Book”), which came to be the most important book from that year on. In July of 1966, Mao took another step in the form of a highly publicized swim in the Yangzi River to symbolize his continued presence and desire to play a greater role in the country.

REAT

P

ROLETARIAN

C

ULTURAL

R

EVOLUTION

Two other prominent figures influenced Mao’s thinking during this time, which by 1966 had culminated in a bold, adventurist policy. Jiang Qing (1914–1991), an actress who had become Mao’s third wife in the late 1930s, was dismayed by the “bourgeois” and “decadent” expressions of culture in the theater and in the arts. Focusing on opera and theater, her areas of special interest, she claimed to be offended by the ideas and values represented in these two art forms. Wu Han (1909–1969), a historian who had written a play about a sixteenth-century official that appeared to be critical of Mao, earned Jiang Qing’s and Mao’s wrath. Criticism of Wu’s production and other artistic works were the first targets of the new movement, which came to be called the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. Within a short time, Jiang Qing would mandate that only six operas, which represented the correct political stance, be performed. Lin Biao, the other prominent supporter of Mao’s radical policies, was the head of the People’s Liberation Army, a highly influential group in the new society. Lin shared Mao’s disdain for the moderate bureaucrats, offering Mao a valuable and powerful ally for his new policies. He joined in the attack against those labeled counterrevolutionaries.

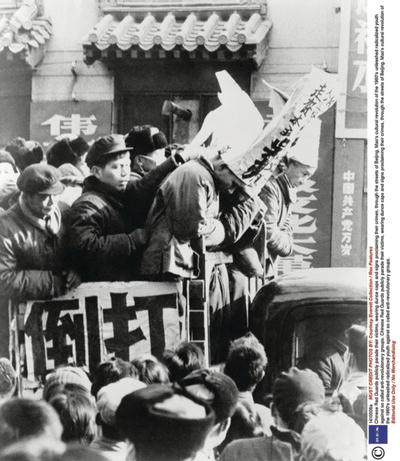

Figure 12.2

Chinese Red Guards publicly parade their victims, wearing dunce caps and signs proclaiming their crimes, through the streets of Beijing. Mao’s Cultural Revolution of the 1960s unleashed radicalized youth against so-called antirevolutionary groups. 1970. Courtesy Everett Collection / Rex Features

Mao and his allies asserted that many in the bureaucracy harbored capitalist views and urged loyal communists to act against them and the “Four Olds”: old customs, old culture, old habits, and old ideas. Students were in the vanguard in these demonstrations and constituted the so-called Red Guards. Mao unleashed these discontented students and young people to challenge the bureaucrats and all those who were allegedly counterrevolutionaries. The closing of schools and colleges permitted students to engage in the struggle against so-called enemies of the revolution, especially those with “old-fashioned ideas” and those with links to the West or Western culture. By late summer of 1966, workers and some intellectuals had joined in the Cultural Revolution campaign, which became increasingly violent. The Red Guards attacked whatever smacked of the old society – monasteries, museums, and elaborate houses and courtyards. They then moved from destruction of objects to harassment of people. Members of the old elite and even Communist Party leaders were compelled to wear dunce caps or to stand in physically painful positions and paraded around the streets. President Liu Shaoqi, who had been regarded as Mao’s successor, was placed under house arrest, beaten, and at times denied his diabetes medication. This mistreatment led to his death in 1969. During the looting and devastation, thousands of people were killed or permanently injured. Intellectuals were perhaps the group that suffered the most, and students, often in collaboration with workers, accused local party leaders of antiparty activism and displaced them. Even more destabilizing were Red Guard and worker takeovers of universities, conservatories of music, and newspapers and magazines. They dismissed experts and sought to manage these institutions on their own, contributing to chaos in education and media outlets. They were prevented from moving into the Forbidden City, military installations, factories, and important artistic and religious sites. However, by early 1967, the top leadership faced difficulties in controlling the fury it had unleashed.