A History of China (84 page)

Read A History of China Online

Authors: Morris Rossabi

IANANMEN

D

ISTURBANCE OF

1989

AND

I

TS

A

FTERMATH

Despite the government crackdowns, students continued to demonstrate against policies limiting freedom and democracy, culminating in a confrontation in spring of 1989. Two unrelated events prompted the crisis. First, in April, Hu died of natural causes. Many students, to whom he had been a hero and who had been chagrined when he had been denounced and had lost his Communist Party position, decided to rally in Tiananmen Square, the true center of political power in Beijing. In addition to mourning his death, they started to demonstrate on behalf of the democratic and economic reforms Hu had championed. They started with rallies and were joined by ordinary citizens, and within a month the pace of protest had quickened, leading to a hunger strike in the square. To be sure, some opportunists had joined the crowds, but the massive number of people indicated considerable dissatisfaction with corruption, nepotism, and lack of freedom of expression. The government temporized and appeared to be paralyzed, prompting the demonstrators to make increasingly dramatic demands, including Deng’s resignation. The second crucial event was the visit of Mikhail Gorbachev (1931–), the secretary general of the USSR’s Communist Party. Many students recognized and revered him as a kindred spirit because of his advocacy of

perestroika

, or “reconstruction of the economy,” and

glasnost

, or “openness and greater freedom of expression.” He represented the economic and political reforms sweeping the USSR, and inspired the students to greater activism and more demands. Zhao Ziyang was viewed as another kindred spirit because he visited the demonstrators.

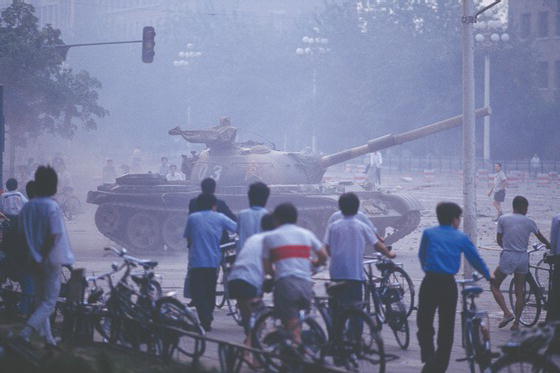

Figure 12.4

June 4, 1989, Tiananmen Square riot. The June Fourth movement, or the 1989 Movement for Democracy, consisted of a series of demonstrations led by labor activists, students, and intellectuals between April 15 and June 4, 1989. © Durand-Langevin / Sygma / Corbis

The more radical the demonstrators grew, the more concerned and intractable the leadership became. A meeting between students and the political leadership did not go well. The government finally acted on the evening of June 3, by trying to clear students and others from Tiananmen. Troops moved in and beat and shot at the demonstrators. In turn, a few demonstrators turned to violence and killed some soldiers. By daylight of June 4, military forces had occupied the square and had dispersed demonstrators. Violence then erupted beyond the square, and ordinary citizens and protestors were killed. Estimates of the dead ranged up to three thousand. Similarly, the government dealt harshly with demonstrators in other cities; many were arrested, although a few, recognizing the perils, left the country.

Deng and his allies had to contend with world reactions to such violence. They could not conceal the military’s use of excessive force because television cameras had witnessed events at Tiananmen. Leaders in many parts of the world condemned the severity of the government’s response to dissent, and the media outside China offered biting critiques of the violence. Deng and other hard-liners appeared to be oblivious to or perhaps feigned ignorance about the reactions of foreigners. Deng himself portrayed the demonstrators as subversives who wanted to destroy the communist system and to impose the dreaded bourgeois control over society. He placed Zhao Ziyang under house arrest and initiated an anti-rightist campaign. He did not denigrate the post-1979 economic reforms, which had encouraged entrepreneurship and liberalization and rapid expansion, but simply excoriated the dissenters for attacking the Communist Party and its leadership and for promoting liberal capitalist policies.

Deng’s formulation characterized Chinese policies from that time on, even after his own retirement in 1992 and his death in 1997. He himself did not opt for the “cult of personality” associated with Mao Zedong. His explicit instructions were to cremate his body and to scatter his ashes at sea. Unlike Mao, he did not have his writings disseminated throughout China, nor did he insist on statues in his honor.

Having dismissed Zhao Ziyang in 1989, Deng assisted Jiang Zemin (1926–), the mayor of Shanghai, to become general secretary of the party, the president of the country, and chairman of the Central Military Commission. After Deng’s retirement in 1992, Jiang continued to support the market economy and dismantled some unproductive state-owned enterprises, leading to considerable unemployment. Zhu Rongyi (1928–), whom he brought with him from Shanghai, became premier and took charge of the economic reform program, which resulted in astounding growth. Zhu sought to modernize state-owned enterprises but also tried to guarantee a social safety net for the unemployed. At the same time, he eliminated taxes on the hard-pressed peasantry and attempted to deal with the growing disparity between the rural and urban areas. His partial success facilitated Chinese entrance into the World Trade Organization, with the attendant advantages, in 2001. However, his economic successes and the emphasis on rapid economic growth came at considerable cost. China was afflicted with urban air pollution, sandstorms, and lakes and rivers overflowing with poisonous residue from factories.

The Jiang/Zhu era also had mixed results in noneconomic areas. China became more engaged in the world and established better relations with many Western countries and, to a certain extent, with Taiwan. Hong Kong and Macao reverted to China, but the government generally did not adopt heavy-handed policies to alter their economic systems. It joined Russia and several central Asian countries to found the Shanghai Cooperation Organization in 2001. The organization focused initially on security and emphasized joint actions against terrorism, intelligence sharing, and military exercises, but it also served as a counter to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and sought to limit US influence in central Asia, especially after the US invasion of Afghanistan and the establishment of US military bases in Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan to eliminate the Al-Qaeda terrorists who had attacked the USA on September 11, 2001. China also attempted to use the Shanghai Cooperation Organization to prevent central Asian countries from aiding and providing sanctuary to Uyghur nationalists, or what it labeled “terrorists,” who sought greater autonomy or independence for Xinjiang, a region that had traditionally had a large Uyghur population.

Ordinary Chinese had somewhat greater freedom during the Jiang/Zhu ascendancy, but the government acted rapidly if it felt threatened. In 1999, government troops suppressed a demonstration by Falungong, a quasi-spiritual and moralistic order associated with the ancient Chinese practice of

qigong

(translated as “life energy cultivation”). The government labeled it an “evil cult” and described its founder, Li Hongzhi (1952–), as a ne’er-do-well. Adopting a strict moral code, spiritual cultivation, exercise, and meditation, the order appealed particularly to women and the elderly. The government tolerated it for a while but by 1999 had begun to perceive it as similar to such subversive secret societies as the Taipings, White Lotus, and Triad. It initiated a media campaign attacking the Falungong ideology and arrested, tortured, or killed quite a number of adherents. The self-immolation of several alleged practitioners of Falungong in 2001 at Tiananmen Square prompted even greater repression of the group. Similarly, the government banned Christian house churches, portraying them as subversive.

Another damaging legacy of the Jiang/Zhu era was its secrecy. Public health was compromised by a lack of transparency. For example, the government tried for some time to avoid acknowledging the extent of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, because admission of considerable drug use and prostitution would cause it embarrassment. A state-run blood-donor project that employed contaminated needles and spread the disease was an even more acute embarrassment for the government, which attempted to conceal the program.

The government of Hu Jintao (1942–), who ruled from 2003 to 2012, had a similarly mixed record. In his previous post as governor of Tibet, Hu had declared martial law in 1989 and had been accused of brutal suppression of Tibetan demonstrators. When he became president, general secretary of the party, and head of the Central Military Commission, he had a mandate of rapid economic development. Yet he faced pressure to protect the poor and those left behind by the sharp economic growth. His government reduced the poverty rate and provided support and a basic safety net for migrants who had moved to the cities and therefore lacked access to medical services and to educational opportunities for their children because they lacked household registration. It pledged to invest more capital in China’s interior, which had not received the same attention as the coastal regions. It even committed itself to protecting the environment and to building better housing and facilities for the bulk of the population. The 2008 Beijing Olympics and the 2010 Shanghai Expo proved to be successful and bolstered China’s image in the world. After some preliminary failures, the government acted expeditiously to deal with the infectious and deadly Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) epidemic.

Despite these successes, Hu and his government failed to fulfill many of their objectives. Income disparity accelerated; environmental disasters continued to be troublesome and resulted in numerous demonstrations against local authorities; cronyism, corruption, and illegal enrichment of officials persisted; and officials illegally colluded with factory and mine owners to expropriate lands from peasants, which also resulted in antigovernment demonstrations. In 2011, Liu Zhijun (1953–), the minister of railways, was accused of accepting $20 million in bribes and of laxness in safety considerations that led to a 2011 collision of a high-speed train and the deaths of forty people. The most sinister and notorious case of corruption involved Bo Xilai (1949–), the son of Bo Yibo (1908–2007), one of the communist movement’s great heroes. Bo Xilai had pursued an initially well-regarded populist policy as leader of the city of Chongqing in Sichuan province, but in 2012 was arrested on charges of extraordinary corruption. His second wife, Gu Kailai (1958–), an attorney and businesswoman who was the daughter of a prominent communist elder, was then convicted of murdering Neil Heywood, an English associate with whom she had had a commercial dispute after years of collaboration in illegal activities.

The government also did not move expeditiously to implement the rule of law or to foster democracy. Despite some professed concerns for national minorities and pledges to support affirmative action, bilingualism in schools, ethnic unity, and religious freedom, the government in Xinjiang encountered considerable turbulence. In 2008, Uyghur activists attacked a police station and killed seventeen policemen. Relations between Uyghurs and Chinese remain tense. Throughout 2012, Tibetan activists immolated themselves to protest Chinese policies – a disastrous blow to the government’s image. Another action that tarnished the government’s image was the 2009 arrest on charges of subversion of the literary critic and human-rights advocate Liu Xiaobo (1955–), who received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010. The rights of Chinese with a lesser profile than Liu have faced similar transgressions.

In sum, since the Tiananmen incident, the communist leadership has tried a mixture of a liberalized economy and a generally authoritarian political system. It has sought to stave off critiques by orthodox Marxists who blamed this policy for the Tiananmen incident and for the abandonment of communist principles. Yet it has also faced denunciations from liberals who resented restrictions on freedom of expression. Government policy has wavered from relaxation of authoritarian policies and freedom of expression in public to repressive policies and detention and imprisonment of critics, even if they had not committed a crime. In repressive times, the authorities have often directed their wrath at civil-liberties attorneys, journalists, and writers. Censorship has persisted in venues ranging from newspapers to the Internet. At times, the central government has refrained from squashing demonstrations against unscrupulous entrepreneurs, corrupt officials, and rapacious factory and mine owners and managers who polluted the environment. Nor has it silenced or detained individuals if they criticized specific conditions and not the system.

Divisions within the leadership have complicated the development of policies. The Tiananmen incident revealed such splits. During the crisis, prominent leaders who had supported the demonstrators lost their positions, and some were denounced. Since then, contradictory views within the top leadership have not readily erupted into the open. Foreigners have not been able to easily identify different factions. Yet the wavering of policies indicates contradictions within the governing elite. The jockeying for power among the top leaders has exacerbated the conflicts in policy. The rise in corruption and bribery has contributed to some of the difficulties. On occasion, corrupt high-level officials have been dismissed, imprisoned, and even executed. Yet considerable corruption has persisted, leading to numerous protests on the local level.