American Eve (11 page)

Authors: Paula Uruburu

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Historical, #Women

By the end of that first year in New York, Florence Evelyn could be viewed in the galleries of the Metropolitan Museum and on “arcade postcards” dispensed from drugstore machines on street corners. With conspicuous consumption rampant, it is not surprising that advertisers quickly saw in her beguiling features the ideal model for the newest female facial products and fashions. If the all-consuming desire of manufacturers was to create and sell an American look, then with the aid of rapidly developing innovations in the machinery of the print media, the growing popularity of new publications aimed primarily at female consumers, the latest methods of marketing an expanding number of new products, and the use of newly invented forms of mass communication, they had found their American dream girl.

Florence Evelyn was dubbed the “modern Helen” by one columnist, and her evocative and soon familiar face launched any number of advertising campaigns as canny entrepreneurs began to capitalize on her uncanny ability to appeal to both sexes and appear chaste and alluring at the same time. It wasn’t long after her first blush as a New York studio model that Florence Evelyn could be found as the cover girl (or inside) of the growing number of women’s magazines, whose inception reflected the demands made by the flourishing market of eager female consumers who were unwittingly willing “slaves of fashion.”

Vanity Fair, Harper’s Bazaar, Munsey’s,

the

Woman’s Home Companion,

the

Ladies’ Home Journal, Cosmopolitan, The Delineator,

and other women’s magazines routinely used Florence Evelyn, who undoubtedly helped boost their circulation.

Restricted circulation of a wholly different kind for female consumers was, however, the uncomfortable result of particularly punishing and macabre trends in the fashions being sold to women in those same magazines. Women were exhorted to wear hair rats, dead stuffed birds, or huge ostrich plumes on equally huge, unwieldy picture hats, and a variety of natural or unnaturally dyed animal pelts with limp heads, abrasive paws, and glassy, lifeless eyes. There were tight leg-of-mutton sleeves and “earshearing celluloid collars,” irritating puffs and bustles big enough to hide a loaf of bread, which prevented easy sitting since they pressed mercilessly on the lower spine. There were rib-crushing metal corsets worn over four additional layers of underclothes to create an unnatural cinched waist; skull-piercing hatpins, unforgiving tight kid gloves, and crippling high-button shoes, which had to be two sizes too small to be chic. There were heavy “hair-shirt” bathing costumes, bathing caps, and itchy black worsted stockings for the seaside, and ground-sweeping skirts on land, which picked up all the dirt and debris from the streets; these heavy skirts, which usually froze in the winter when wet with snow or slush, required

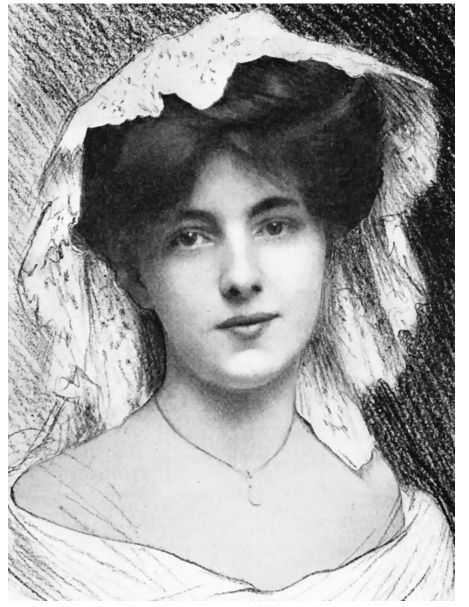

Artist’s rendering of Miss Nesbit, 1901.

women to always have at least one hand free to liberate themselves from the tenacious ice and rubbish trapped within their treacherous trailing folds.

In 1901, being in fashion inevitably meant being incapacitated and in pain from head to toe, the result of “induced pathological features” for all aspiring models of “pecuniary decency.” All, that is, but the nation’s newest model, who would help to change the feminine ideal. In spite of her steady employment, Florence Evelyn could not afford most of what she modeled, and unless it was necessary for a photo session, the petite sixteen-year-old had no need for the confinement of corsets, bras, or layers of underclothing; she was happily unrestrained by the contraptions of comeliness and “vulgar tradition,” which she nonetheless helped sell to an eager female population.

THE SACRED AND THE PROFANE

Within a short time, Florence Evelyn (or some part of her) was selling everything from subscriptions for the

Woman’s Home Companion

, Fairy soap, ocelot furs, Lowney’s chocolates, Sunbonnet Oleo, and sewing machines to Rubifoam dentifrice, an early form of powdered toothpaste, which she admitted in later years “tasted like gritty talcum.” Nor did it take long for the girl who had begun her career assuming childish heavenly poses to find herself on beer trays, cigarette and tobacco cards, celluloid pin backs, cigar labels, advertising fans, wallpaper, pyrographic pillows, playing cards, and pocket mirrors with the unfortunate “good for ten cents in trade” often written around the circumference of the mirror encircling her photo. Given out mainly in hotels from New York to Wyoming, these were innocent enough advertising tokens, although many of the men who were the predominant patrons in the hotels kept them in secret places, hidden from wives and girlfriends.

As part of her newly minted celebrity, Florence Evelyn also became the first recognizable and bona-fide pinup girl. She was a calendar girl for such notable entities as Prudential Life Insurance, Swift’s Premium, Pompeian face cream,

Youth’s Companion,

and Coca-Cola, for which the images of her marketed for public consumption were of the maidenly variety.

Another natural place for her image was sheet music, which was itself a kind of mania at the turn of the century. But while imaginary Daisys and Rosies had their place at pianos in countless households, the very real Florence Evelyn had songs written especially for her by lovesick admirers who paid to have their pieces published. One was Vincent Spadeo, who wrote the cleverly named “Nesbit Waltz,” whose sheet music had on its cover a photo of Evelyn identified as the “Kimono Girl.” Another piece was written by a smitten physician from New Jersey and titled “Love’s Pleading,” also featuring a photograph of an angelic-looking Florence Evelyn and published in a Sunday supplement.

Looking back on the first months of her mercurial success at such an impressionable age, Evelyn recalls in her memoirs that her youthful dreams were still vague at that point, and nothing in particular grabbed her attention beyond the happy accidental career that landed her in the Garden of the New World. While she was not “insensible to the possibilities of a career on the stage,” as she described it, her “enthusiasm was for the present.” One thing she seemed sure of, however: given the limited sphere of influence and choices that she said bound women “like so many Chinese feet,” she was determined she would never become a domestic drudge, a wifey, or a drone. As she describes it, by sixteen she “already look[ed] back upon the life domestic with the interests and curiosity which the mountaineer reserves for the plains he has quitted.” She had seen what a dead end that proved to be for her mother and her wretchedly extinguished spirit. And so she began to nurture the notion that she should go on the stage.

As Florence Evelyn’s father became a fond memory and a more remote presence in his daughter’s mind, initially Mamma Nesbit seems to have attempted to make up for that void by becoming overwhelmingly, stiflingly present, relentlessly peddling and protecting her daughter (badly), sheltering her (badly) even as she exploited her youthful looks. But contrary to popular myth, Mrs. Nesbit was not the archetypal ambitiously shrewd and calculating stage mother, which meant that her daughter’s accidental career seemed to move forward with its own careless and inadvertent momentum.

As the weeks passed, Florence Evelyn’s theatrical urge buzzed in and out of her bonnet. By the fall of 1901, the model, her mother, and Howard were all living off her still small but respectable wages in a boardinghouse on West Thirty-sixth Street between Fifth and Sixth avenues. Although Florence Evelyn’s earnings were more than what the three Nesbits combined had made at Wanamaker’s, they were hardly enough to pull them all safely out of the shadow of sometimes mean and meager survival in the costly life of Manhattan. Nor were they likely to fund Evelyn’s dreams of becoming one of the “smart set.” Howard became an increasingly infrequent inhabitant and “lost soul,” being sent away usually for at least two weeks out of any given month, since Mamma Nesbit fretted that the city might be an unhealthy place for such a sensitive boy.

And then the little Sphinx, her eyes trained in another direction, found a new audience, which, unbeknownst to her, included the Pharaoh of Fifth Avenue, whose realm had swelled from his estate, Box Hill, to Byzantine empires and back again to Broadway and the borders of the Bowery.

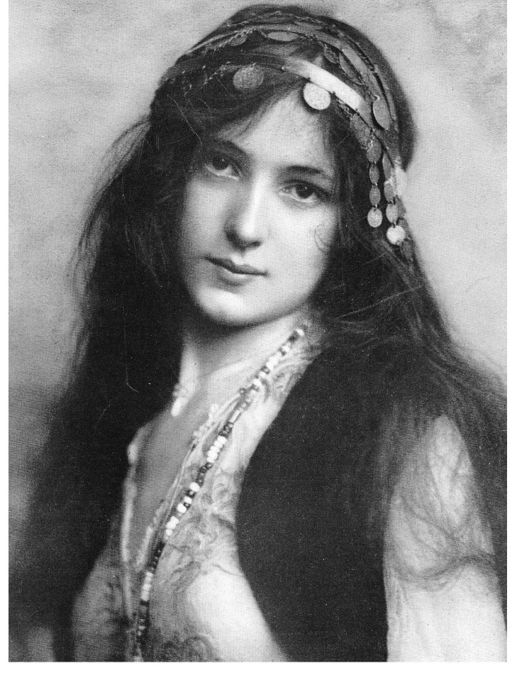

Evelyn in

The Theatre

magazine, 1902.

CHAPTER FIVE

Florodora

The only people who never talk about themselves are Japanese, bank robbers, and ambassadors.

—Evelyn Nesbit, My Story

Tell me, pretty maiden, are there any more at home like you?

—Song lyric from Florodora, 1901

In a city alive with the constant clamor and din of distraction, Florence Evelyn found herself burdened with long hours of confined inactivity and nerve-racking silence, sometimes seven days a week. Her life had become a monotonous rusting chain of sittings and appointments, always lasting into the twilight hours—and almost always within arm’s reach of her wearisome mamma, in tow like a barge incapable of pulling its own weight. So within only six months of her arrival in New York City, the unofficial queenlet of the studio and advertising hearts had already begun to seriously consider abdicating the stifling linseed-stained and flash-powdered skylight worlds she had reigned over, where the high point of her day was having a cup of oolong tea before posing again in absolute stillness for several hours. She also began to wonder if life in the alternately arid or oily airless studios might have a withering effect on her, and at the seasoned age of sixteen feared becoming merely a pressed flower, something formerly moist and thriving, crushed and forgotten between faded pages and kept on a shelf.

Invariably, the girl model also found herself thrust solely into the company of adults, mostly very grown-up men whose one desire, usually, was that she not speak or move. There were other times when, for a fleeting second or two, she felt that certain lingering looks on the faces of certain artists were not motivated “by a desire to simply achieve the right perspective. ” But as she reclined against a papier-mâché tree, her hand held out to a stuffed bird fastened to a simulated fountain with chicken wire, or fixed her engaging sphinxlike smile on a phantom object of affection, the more she was convinced that the stage offered greener façades.

Almost from the moment her enchanting face and supple figure appeared in the pages of Manhattan’s magazines and newspapers, Florence Evelyn had begun to receive all manner of dazzling as well as less than shining offers of fame from theatrical “types” who had no knowledge at all of whether she possessed any talent. Most came in the mail; some came right to the front door of her boardinghouse. Theatrical producers, legitimate and spurious alike, showed up only days after some of her earliest modeling photos appeared in both the

Journal

and the

World.

The would-be managers laid at her dainty feet mock-up playbills and advertisements with her photos; they talked of commanding high salaries and assured her that she would be a star. One unwitting prognosticator said glibly that the little looker would be “the most talked-about girl in America.”

But, whether it was her mother’s tunnel-visioned skepticism about a notoriously fickle and, she suspected, low-paying profession or the near-sighted overconfidence of youth on Florence Evelyn’s part, initially the teenager and her mother rejected outright anyone who offered her the chance to capitalize on her name through “freakish notoriety,” not wanting to risk a week with no paycheck and a return to stale Weetabix.

Contrary to the popular notion that her mother pushed Evelyn from the womb onto the stage is the fact that Mamma Nesbit was more than reluctant to give in to Florence’s growing desire to pitch posturing for “real acting.” After all, she was making good money as a model—at times almost twenty dollars a week. “They” had developed a faithful clientele of metropolitan artists, illustrators, and advertisers in a relatively short time just as “they” had in Philadelphia, which guaranteed a steady income. As she fretted unceasingly over the family’s financial state of affairs (with Howard at this point once again somewhere with somebody no doubt in need of something), Mamma Nesbit actively discouraged her daughter’s theatrical ambitions. While neither she nor Florence Evelyn had any idea what a chorus girl’s weekly salary was, even if her dreamy-eyed daughter didn’t always take that into account, Mrs. Nesbit did her own accounting. There was, of course, the seedy reputation of the theater to consider (with its loose morals and tight costumes), but that aspect seemed of less consequence to Mrs. Nesbit than the monetary issue.